Nebraska’s Sales Tax

Report Summary: Nebraska’s Sales Tax

Abstract and Policy Recommendations

Many economists, policy advisors, and lawmakers agree that changes need to be made to the state’s sales tax law in order to enable Nebraska to achieve significant, sustainable tax reform. Reducing reliance on the property tax through ending Nebraska’s many sales tax exemptions can help create the right environment for revenue-neutral tax reform that improves the state’s overall tax climate.

Changes to the sales tax can not only help alleviate other burdensome taxes but modernize Nebraska’s tax code and create a tax system that is beneficial to future generations. Tax laws need to adapt to a changing economy while also being pro-growth; promoting entrepreneurship and job creation. If these end goals are at the forefront of tax reform discussions, Nebraska will be on the path to greater prosperity.

There are several broadly accepted standards and observations about sales taxes by both economists and public finance experts. These principles are found throughout this paper and should be the guiding forces for any Nebraska tax reform including the sales tax.

- An ideal sales tax is imposed on all final consumption, both goods and services;

- An ideal sales tax exempts all business inputs to avoid tax pyramiding;

- Sales taxes should be destination-based, meaning that tax is owed in the state and jurisdiction where the good or service is consumed;

- The sales tax is more economically efficient than many competing forms of taxation, including the income tax, because it only falls on present consumption, not saving or investment;

- Because lower-income individuals have lower savings rates and consume a greater share of their income, the sales tax can be regressive, though broadening the base to include additional consumer services (much more heavily consumed by higher-income individuals) represents a progressive change;

- The sales tax scales well with ability to pay because it grows with consumption and is, therefore, more discretionary than many other forms of taxation; and

- Consumption is a more stable tax base than income, though the failure to tax most consumer services is leading to a gradual erosion of sales tax revenues as services become an ever-larger share of consumption.[1]

Introduction

There has been a lot of discussion about sales taxes in Nebraska over the last couple of years. This is because the sales tax has been identified as part of the solution to the state’s high property tax problem, and therefore, many aspects of the sales tax were debated during the 2019 legislative session. This paper serves as an overview of the sales tax in Nebraska and some possible reform options policymakers should consider as the debate on sales tax reform continues.

It has been the position of the Platte Institute for many years that Nebraska’s sales tax is outdated and needs reform. Although the state adopted its first sales tax in 1967, the structure and design of the tax mimic those adopted in the 1930s. Since this time, Nebraska’s economy has changed, and the tax structure must do the same.

This paper will explore many aspects of raising new revenue through the sales tax, but by no means is this a guide for how to INCREASE taxes on Nebraskans. The Platte Institute’s goal with this policy study is to serve as an educational guide to policymakers, aiding them as the debate on sales and property tax continues with an end goal of comprehensive tax reform that reduces the burden of Nebraska’s high tax rates.

What is a sales tax?

A sales tax is considered an ad valorem tax, that is, a percent of the price of the item is added to the final purchase amount when the item is purchased. For example, if you purchase a shirt for $15.99 with a sales tax rate of 7 percent, your total bill will be $17.11 due to the tax.

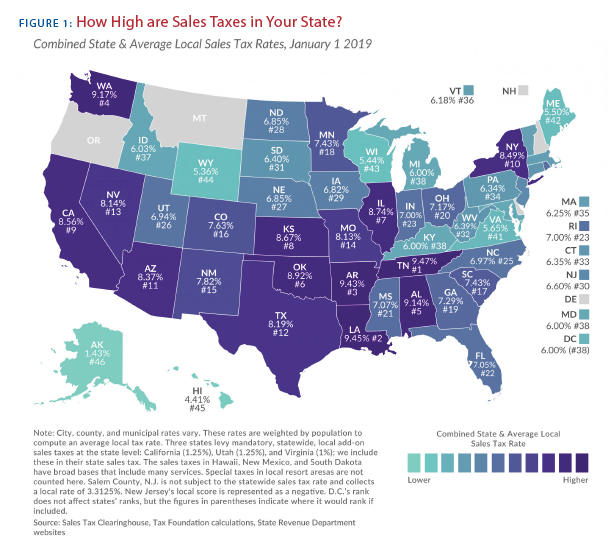

In economic terms, a sales tax is a consumption tax because it is levied when someone “consumes” or buys a product. Sales taxes are levied at both the state and local level and commonly exempt certain items from taxation. Each state has autonomy over its sales tax. This means each state exempts different items and each state has a slightly different structure than the others. This can vary from some states choosing not to levy a sales tax at all while others rely on the sales tax as their main source of state tax revenue. Some states have a significant number of exemptions where others have very few. As of 2019, 45 states and the District of Columbia collect a statewide sales tax while local sales taxes are collected in 38 states[2]. The federal government does not levy a sales tax and has left this to the states as a revenue source.

What is NOT a sales tax

Some confusion can arise when the discussion transitions to a value-added tax (VAT) or an excise tax. These are different types of taxes, and while they have similar features, they do not operate as a sales tax would.

More than 130 countries use value-added taxation around the world. A VAT is assessed and collected on the gross margin at each point in the manufacturing, distribution, and sales process of an item. This is in direct contrast to a sales tax which ideally should only be assessed and paid by the consumer at the very end-stage. There are no states that levy a VAT.

The other tax confused with a sales tax is the excise tax. Unlike the sales tax, the federal government frequently uses the excise tax on items such as gasoline, alcohol, and tobacco. The excise tax was first used and is still used today to alter people’s behavior by way of taxation. Therefore, excise taxes are commonly referred to as “sin taxes” because they are levied on items policymakers deem unfavorable. In practice, an excise tax is based strictly on quantity; the consumer pays a flat amount per item.

Another difference is that VATs and excise taxes lack transparency because they are commonly included in the final price of the item, whereas a sales tax is applied at the final sale and itemized on the receipt.

History of Nebraska’s Sales Tax

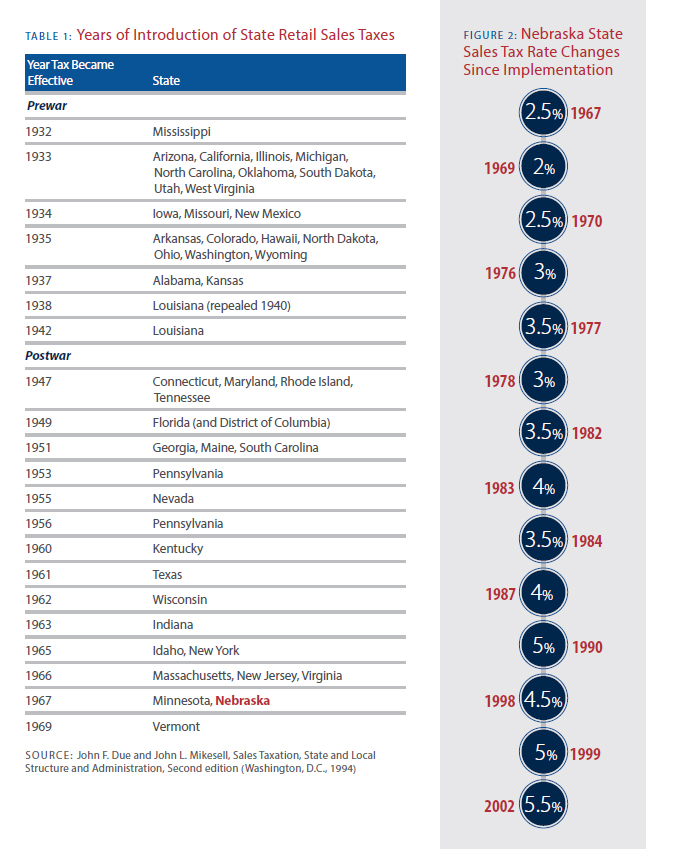

From a national perspective, the sales tax was created during the Great Depression in the 1930s when property tax revenue, the main revenue source for states at the time, dropped considerably. Nebraska was one of the last states to enact a sales tax, which gives it a more recent sales tax history than most states. A voter-approved constitutional amendment abolishing the state property tax in 1966 forced the Legislature to adopt new tax policies for the state, resulting in the creation of the state sales and income taxes in 1967.

The sales tax was originally structured to focus on the final retail sale of any item of tangible personal property or goods. At the time, Nebraska’s economy was primarily goods-based. Unlike most goods, services sold to the final consumer are not taxed unless specifically mentioned in Nebraska’s sales tax law[3]. This has become a problem because Nebraska’s economy has changed over time into a more service-based economy. Because services are mostly exempt from the sales tax, only one-third of what is purchased in Nebraska is now subject to the state and local sales tax[4]. The exclusion of most services means that as the service sector grows, the amount of revenue the sales tax can generate is being eroded.

Prior to the passage of the 1967 Sales Tax Act, the Legislature commissioned a study to focus on the design of a retail sales tax. This study recommended that business-to-business sales or business inputs be exempt, a structural principle that still exists in today’s law that is supported by economists as a sound tax policy[5]. The original state sales tax rate was 2.5 percent. It has changed 13 times since then and is now 5.5 percent[6].

Nebraska’s Local Sales Tax

Many Nebraska cities levy local sales taxes in addition to the state rate. Under current state law, cities and counties can levy their own sales tax with voter approval, and it can be set at ½, 1, 1½, 1¾, or 2 percent of the retail sales within the boundaries of the city[7]. However, cities of the metropolitan class (Omaha) are not allowed to levy a local sales tax above 1½ percent[8]. This additional local sales tax in many cities places the average combined sales tax rate in Nebraska at around 7 percent, although many cities are higher.

Twenty-seven cities levy a 2 percent tax, for a total state and local combined rate of 7.5 percent. The city of Lincoln is the only one to levy a 1¾ percent tax while a 1½ percent rate is levied by 112 cities. Ninety-seven cities have a local rate of 1 percent, and only two jurisdictions, Dakota County and Upland, have a local rate of ½ percent[9]. Currently, Dakota County and Gage County are the only counties authorized to have a sales tax[10].

Because the expansion of Nebraska’s sales tax base discussed in this paper would increase tax receipts for local governments with sales tax authority, the new revenues could potentially be used to reduce local sales or property tax rates.

Economics of the Sales Tax

Every tax has an economic impact, but some have more than others. In the United States, governments pay for their services through revenue generated by taxing three primary economic bases: income, consumption, and wealth. Not all taxes work the same way, and each has a different impact on the economy. However, in all three types, the size of the tax base is critical to the revenue generation of the tax because there are economic, social, and political limits on the ability to adjust the statutory rates. In this section, we will focus on the economic aspects of the sales tax, or the tax on consumption.

Sales Tax Base

Simply put, a tax base is the total amount of items that a government can tax. This is where the discussion of exemptions comes into play. For example, if there were zero sales tax exemptions, then the base would include every transaction that takes place within that taxing jurisdiction. When an exemption is introduced, that item is no longer subject to the tax, so the base gets smaller. Economists call this an “erosion of the base.”

A common agreement among economists and public finance scholars is that a well-structured sales tax should extend to all final consumer transactions, whether goods or services, but exclude business-to-business inputs.

However, most states fall far short of this ideal. While there is an economic argument for an exemption of business inputs, other exemptions are made based on political justifications, not a true economic rationale.

Exempting goods and services arbitrarily makes expanding the sales tax base difficult. While it is preferable to have fewer sales tax exemptions, it would also be correct for opponents to say that including some additional products or services in the sales tax base while excluding others can also seem arbitrary, and is an example of “picking winners and losers.”

Though policymakers may intend to make the sales tax less burdensome for their constituents by supporting exemptions, in practice, narrowing the base requires higher sales tax rates to raise the same amount of revenue and adds more complexity to the tax code.

Though it is a counterintuitive idea, the fairest sales tax for taxpayers and tax-collecting businesses is one that only exempts business inputs and includes all final consumer goods and services. This policy enables the lowest possible tax rate to be collected on goods and services and has the simplest rules for compliance.

Sales Tax Breadth

The sales tax breadth is a way of measuring or calculating what percent of the economic base is subject to the tax. For example, when states started levying a sales tax in the 1930s, the tax applied to almost all items a person would purchase, creating a high sales tax breadth. Today, many states have chosen to exempt multiple items from the sales tax, which reduces the breadth.

In addition to certain tangible items now being exempt from the tax compared to the base of decades prior, the U.S. economy has changed from a manufacturing-based economy to a service-based economy. This has led to Americans purchasing more services than goods as a percentage of their overall consumption. In the first quarter of 2019, services accounted for approximately 70 percent of personal consumption expenditures in the United States, whereas goods were only 30 percent[11]. Nebraska’s economy has followed a similar trend,[12] as seen in Table 2.

Table 2: Total Personal Consumption Expenditures in Nebraska

|

|

2017 |

Percent of Total |

| Total personal consumption expenditures (in millions) |

$77,111.1 |

|

| Goods |

$26,356.6 |

34% |

| Durable goods |

$9,277.1 |

12% |

| Motor vehicles and parts |

$3,821.2 |

5% |

| Furnishings and durable household equipment |

$2,085.8 |

3% |

| Recreational goods and vehicles |

$2,035.2 |

3% |

| Other durable goods |

$1,334.8 |

2% |

| Nondurable goods |

$17,079.5 |

22% |

| Food and beverages purchased for off-premises consumption |

$5,557.2 |

7% |

| Clothing and footwear |

$1,928.8 |

3% |

| Gasoline and other energy goods |

$3,196.5 |

4% |

| Other nondurable goods |

$6,397.0 |

8% |

| Services |

$50,754.5 |

66% |

| Household consumption expenditures (for services) |

$48,221.6 |

63% |

| Housing and utilities |

$11,926.9 |

15% |

| Health care |

$13,881.7 |

18% |

| Transportation services |

$2,040.9 |

3% |

| Recreation services |

$3,006.0 |

4% |

| Food services and accommodations |

$4,378.1 |

6% |

| Financial services and insurance |

$7,602.8 |

10% |

| Other services |

$5,385.1 |

7% |

| Final consumption expenditures of nonprofit institutions serving households |

$2,532.9 |

3% |

| Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis |

If Nebraska does not take this economic change into account, this will lower the breadth of the sales tax automatically. Because the reduction in breadth reduces the revenue potential of the tax, many states have chosen to increase their sales tax rates in order to maintain constant revenues, rather than adjusting their base/breadth. Nebraska is no exception.

Many economists involved in state-based policy use the late Indiana University Professor John Mikesell’s standard measure of sales tax breadth, which is defined as the ratio of the implicit sales tax base to the state’s personal income[13]. As of Fiscal Year 2017, Nebraska had a sales tax breadth of 34 percent, which ranked 27th highest in the nation. However, neighboring South Dakota, which applies a very broad-based sales tax, has the second-highest breadth in the nation at 62 percent[14].

Table 3: Nebraska and Neighboring States’ Sales Tax Breadth

| State | Sales Tax Breadth | National Rank |

| Nebraska |

34% |

27th |

| Colorado |

34% |

28th |

| Iowa |

37% |

22nd |

| Kansas |

36% |

25th |

| Missouri |

32% |

32nd |

| South Dakota |

62% |

2nd |

| Wyoming |

45% |

7th |

| Source: Tax Foundation; 1st = most breadth | ||

While a higher sales tax breadth is a good thing as it applies to the taxation of the final sale of consumer goods and services, this measurement also includes goods and services that may be business inputs. Therefore, while policymakers should seek to expand the sales tax breadth by eliminating unjustified sales tax exemptions, it is important to know that it is also possible for a sales tax to have too great of a breadth. For example, while South Dakota’s sales tax includes a wider range of consumer services, which is consistent with the consensus of public finance scholars, the tax also includes a significant number of business inputs. The next section will explain the economic problems with taxing business inputs, and why it should be avoided.

Tax Pyramiding

As stated elsewhere, the ideal sales tax should include all final consumer transactions, whether goods or services, but exclude business-to-business inputs.

This is good and economically sound tax policy not because businesses deserve special treatment, but because failure to do so results in what is called “tax pyramiding.”

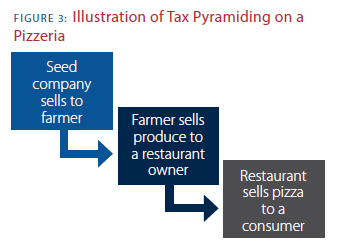

If the tax is levied on business inputs, then the tax will be embedded in the final price of the good or service several times over. Figure 3 provides a very simple example. If sales tax is applied to the tomato seed the farmer plants, and then is applied to the tomato the restaurant owner purchases, and then again on the pizza purchased by a customer – the sales tax is embedded 3 times into the final price of the pizza. While this is a simplified example, it illustrates that this pyramiding of the sales tax ultimately increases the cost of doing business, and more times than not, also increases the final cost for the consumer.

Tax pyramiding is particularly burdensome in industries with long production lines and with many components, such as agriculture-based products and manufacturing. The economic consequence is that businesses will try to avoid these taxes and change their operational structure in ways that would not be otherwise economically efficient. In addition, tax pyramiding undermines one of the benefits of transparency provided by the retail sales tax over the VAT or the excise tax. When states tax business-to-business transactions, the embedded taxes are already in the final price of the product, unbeknownst to the consumer.

However, states face difficulty with determining exactly which products are business inputs and which are not. Many states, including Nebraska, try to engage in the difficult task of picking products that are frequently used as business inputs and individually carving out exemptions for them in the sales tax code. This approach is a step in the right direction but does not and cannot ever comprehensively address all the items that businesses use in the production process, which should not be subject to sales tax. A more straightforward approach would be to give businesses an identifying card to present to retailers when making business purchases that exempt them from the tax on whatever they are buying.[15]

Regressive Tax

Many refer to the sales tax as a regressive tax, which is an accurate description. By definition, a regressive tax is when a tax takes a larger percentage of income from low-income earners than from high-income earners because it is levied uniformly to all situations. This is the direct opposite of a progressive tax, which takes a larger percentage from high-income earners such as the graduated income tax that is applied at a higher rate the more income you earn.

For example, if someone only makes $25,000 per year and they buy $2,500 in taxable goods during that same year, they are paying sales tax on 10 percent of their total earnings. If someone makes $50,000 per year and they buy the same $2,500 in goods, they are only paying sales tax on 5 percent of their earnings. Although the tax is the same rate in both scenarios, the person with the lower income is paying a higher percentage of their income, which makes the tax regressive. Other taxes that are considered regressive are user fees and property taxes.

However, it must be noted that sales tax exemptions can exacerbate the regressive effects of sales taxes. Under current law, Nebraska exempts most services from the sales tax base. Yet, a greater proportion of services are consumed by wealthier households versus low-income households. Because these sales are exempt, the sales tax rate paid on taxable goods consumed by low-income taxpayers must also be higher to collect the same revenue, making the regressive impact of the tax greater.

Many citizens and policymakers assume that an ambitious expansion of the sales tax base must necessarily make the state tax system more regressive or more costly for low-income taxpayers. If Nebraska were to use revenues raised from an expansion of the sales tax base to reduce property tax and sales tax rates, which are both considered regressive taxes, the overall tax climate for lower-income taxpayers could be improved.

Tax Shift

Many that debate changes to the sales tax argue that it is a tax shift. By definition, a tax shift is when there is a redistribution of a tax burden from one entity to another. In the private sector, this is illustrated by a producer shifting the cost of the tax onto the consumer.

In the case of government and the sales tax, many states have broadened the sales tax base to reduce the regressive nature of the sales tax by including services. They use this revenue to either reduce the sales tax rate or to reduce other tax rates, such as the income or property tax. This negates the idea of a “shift” because the taxpayer is receiving a reduction in their tax burden somewhere else in the code.

The only way Nebraska would be guilty of conducting a “tax shift” is if they broadened the sales tax base and increased the rate with no other tax changes. This is because the end result would be “shifting” of the revenue burden from one tax onto another. For example, many states have broadened their sales tax base in order to reduce the income tax. In Nebraska’s case, many have proposed that the revenue generated from broadening the sales tax should be used to reduce the property tax. In both cases, there is a redistribution of tax revenue from one tax to another, but the net impact for many taxpayers is neutral because there is an accompanying cut. That is why sales tax changes are so commonly included in comprehensive tax reform packages.

Nebraska’s Sales Tax in the Current Environment

Nebraska is currently tackling a growing property tax problem, and many have turned to the sales tax as a way to reduce the state and local governments’ reliance on property taxes. Lawmakers are not unwise to turn to the sales tax. One of the ideal policies that should be explored for much-needed tax reform is an expansion of the sales tax base as a tool for lowering state and local tax rates.

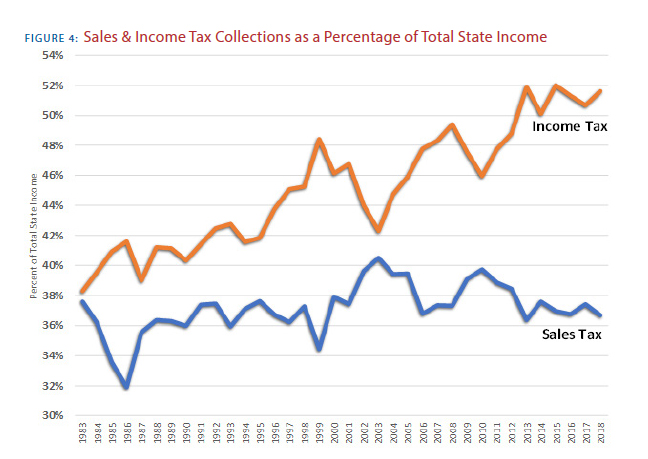

An evaluation of Nebraska’s sales tax collections over time shows that there is clearly room for greater reliance on the sales tax. Despite increases to the state sales tax rate and the approval of more tax exemptions, the sales tax has not become a more effective revenue source for the state. As we can see from Figure 4, the state is relying more heavily on the income tax than the sales tax. The sales tax has been at a relatively consistent average of 37 percent of total state tax collections over the last 40 years, whereas the income tax has averaged 45 percent, reaching a high of 52 percent[16].

It is clear in the last fifteen years or so that changes in consumer behavior are contributing to the erosion of the sales tax, with untaxed services assuming an ever-greater share of personal consumption. The consequence is that the existing sales tax base is taxed at a higher rate than would otherwise be necessary. Another consequence is that the income tax, which is considered by economists to be less pro-growth than the sales tax, has emerged as the dominant state tax.

Another conclusion worth noting from this and other data are that the sales tax is a more stable tax base than the income tax. As you can see in the above chart, in periods when Nebraska and the nation experienced recessions (1990-91, 2001, 2007-09) the sales tax remained as a constant source of revenue, while the income tax was much more volatile. When the state has obligations to fund such as Medicaid and public education, it cannot be subject to wide swings in revenue, because these operations must function regardless of the economic climate.

Sales Tax in Tax Reform in Other States

Other states, namely North Carolina and Utah, have experienced the same divergence between their sales and income tax as Nebraska. North Carolina addressed this problem by broadening the base of their sales tax to include services and many exempted goods. In exchange, their overall tax code was reformed to encourage entrepreneurship, economic growth, and job creation[17]. As a result, for the five years immediately following tax reform, North Carolina has seen revenue surpluses in each year, with a surplus amounting to 3 percent of state revenue in 2019, or $700 million above projections along with record job growth[18].

Utah, on the other hand, is currently in the process of debating a tax plan that would lower the rate and broaden the base to address the overreliance on income tax and take advantage of many of the untaxed services in the state[19]. Utah is currently experiencing economic growth and the state leadership wants to see this trend continue, which is the rationale for reform of the sales tax.

As far as leveraging the sales tax as a tool for broader tax reform, both Iowa and Kentucky did this in 2018. While Kentucky’s tax reform package was a net increase in revenue, it was a necessary change to address the state’s growing pension problem and lack of diversified revenue sources. Kentucky broadened the sales tax base by including many services, using the new revenue to create a lower flat-rate personal and corporate income tax which also had fewer exemptions. Iowa broadened its sales tax base to include transactions that were exempt in order to lower other tax rates and to simplify the overall tax code.

Iowa, Kentucky, and North Carolina have all broadened their sales tax base to make their states more friendly to investment through comprehensive tax reform. Utah will more than likely join this group next year by taking the very same approach.

Competitiveness

Iowa, Kentucky, North Carolina, and Utah have all found that taxing services and broadening their sales tax base does not hurt their economic competitiveness with other states. Nebraska needs to take the same approach at a minimum.

Unlike most of these states, though, Nebraska faces an enormous challenge with property taxes that are among the nation’s highest, and that continues to rise in some areas. It will take more than a token sales tax base expansion to reverse that trend. For this reason, the Nebraska Legislature should begin the conversation with the knowledge of how much tax reform could be delivered if all consumer sales tax exemptions were eliminated.

In Table 4, a hypothetical situation is calculated to illustrate the amount of sales tax available if there were zero exemptions. We understand in this situation that business inputs would be taxed, which we do not support. However, since the exact figure is almost impossible to calculate with all the varying exemptions in the tax code, this shows that the maximum collections from a sales tax with zero exemptions are around $4.2 billion. In 2017, there was $1.8 billion in sales taxes[20] collected by the state, which equates to only 43 percent of the maximum available. If the Legislature were to remove many, if not all, of these sales tax exemptions on services that are not business inputs, then a significant amount of revenue could be generated to offset the excessively high property tax.

Table 4: Hypothetical Sales Tax Revenue

|

|

2017 |

Hypothetical 5.5% state sales tax applied |

| Total personal consumption expenditures (in millions) |

$77,111.1 |

$ 4,241 |

| Goods |

$26,356.6 |

$ 1,450 |

| Durable goods |

$9,277.1 |

$ 510 |

| Nondurable goods |

$17,079.5 |

$ 940 |

| Services |

$50,754.5 |

$ 2,791 |

| Household consumption expenditures (for services) |

$48,221.6 |

$ 2,652 |

| Final consumption expenditures of nonprofit institutions serving households |

$2,532.9 |

$ 139 |

| Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis |

There are other criteria that policymakers can use if they cannot reach a consensus on sales tax reform that includes all final consumer goods and services in the sales tax base.

A comparison to other states can provide an assessment of whether Nebraska faces a competitive disadvantage by levying a sales tax on a good or service. However, this process must be viewed with appropriate skepticism. After all, most states do not currently levy sales taxes in accordance with sound tax policy principles, and some states are continuing to narrow their sales tax bases.

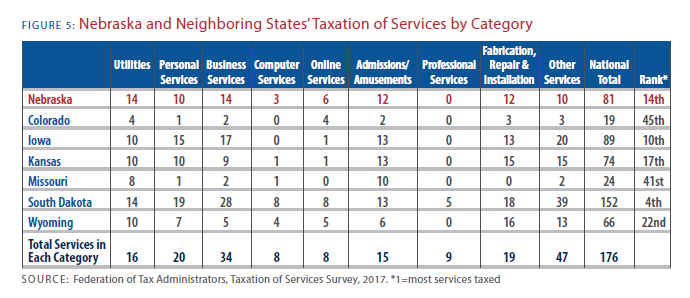

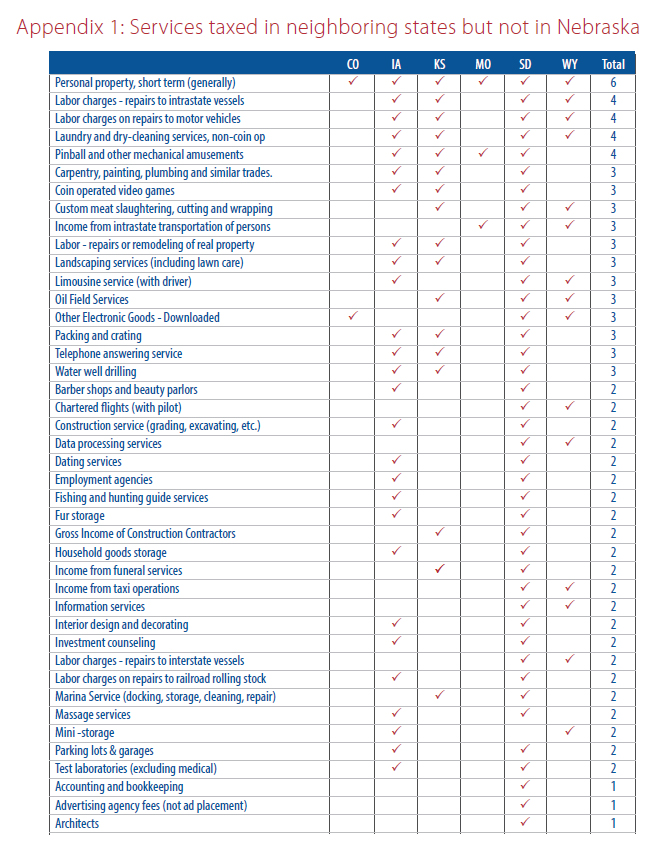

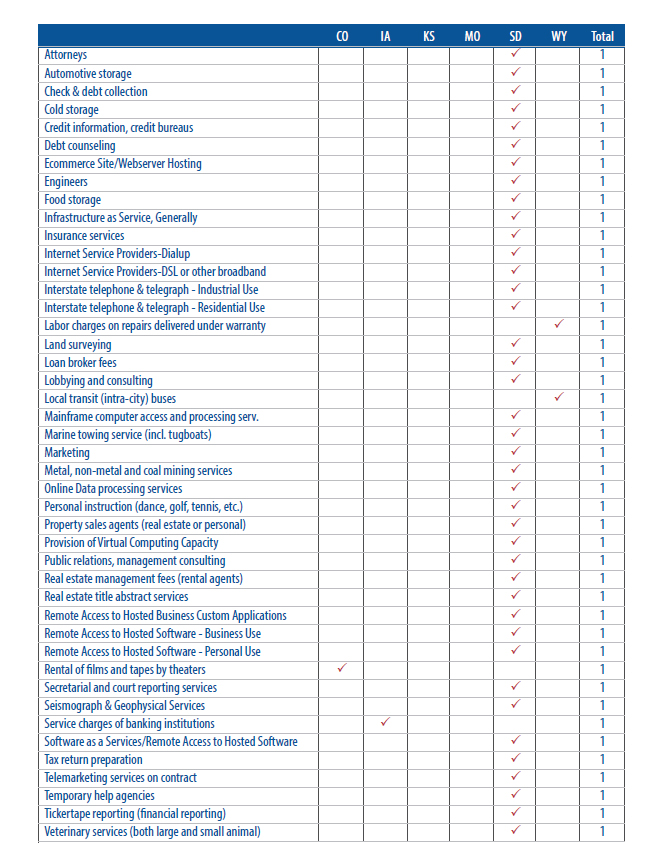

Still, these criteria will show that Nebraska has much room for improvement. For example, there are 79 services that one of Nebraska’s neighboring states tax that Nebraska currently exempts, and each of these could clearly be included in a reform plan without any economic objection. These include landscaping services, veterinary services, data processing services, investment counseling, massage, personal instruction (dance, golf, tennis, etc.), and chartered flights with a pilot. (See Appendix 1 for the entire list of services)

As mentioned in the section on regressivity, the taxation of groceries, prescription and nonprescription drugs and other staples is a major area for objections to sales tax reform. However, it is also a significant source of foregone revenue. Right now, there are 5 states that do not levy a sales tax at all and only 9 additional states that have chosen to exempt all three of these categories from the sales tax. (See Appendix 2 for the nationwide state list)

Table 5: State Count on Taxation of Groceries and Drugs

| Item | Number of States |

| Groceries | 16 States* |

| Prescription Drugs | 1 State* |

| Nonprescription Drugs | 36 States |

| *Some only levy a local tax or a tax rate lower than the state rate | |

While many are accustomed to referring to a sales tax on groceries as a tax on “food,” in practice, many food products Nebraskans consume daily are already subject to sales tax. Prepared meals and beverages at restaurants and fast food establishments are taxed in Nebraska, as are food products purchased at grocery stores that are heated, such as a rotisserie chicken. Nebraska currently exempts all unprepared groceries and prescription drugs, while taxing nonprescription drugs.

It should be noted that while levying a special, lower state or local sales tax rate on groceries is a possible compromise with the potential to raise revenue, it does add complexity to the tax code. Preferably, policymakers should levy the same uniform sales tax rate on all goods and services. By ending more exemptions, state and local governments will have more revenue to arrive at the lowest possible rate.

To see more details on how other states tax particular goods and services, please reference the tables found in the Appendix.

Revenue Impact of a Sales Tax Rate Change

Because this paper recommends reducing Nebraska’s state sales tax rate as part of comprehensive tax reform, it would be essential for policymakers to be able to assess the cost of these changes. When a tax rate is changed, economists calculate how much the tax will either increase or decrease the government’s revenues. There are two very different types of calculations that exist, “static scoring” and “dynamic scoring.” When static scoring is used, it assumes that the tax change will have no impact on the economic behavior of the individuals that are affected. Dynamic scoring ads to the calculations the predictable impact tax changes will have on economic behavior.

For example, when Oregon increased its income tax rate, the state expected to have more revenue–this is a static scoring scenario because the behavior of citizens was not taken into consideration. What happened in practice was that people moved out of state and Oregon collected LESS revenue, even with the higher rate. If dynamic scoring had been conducted, then the behavior of these citizens would have been measured, and the revenue projection probably wouldn’t have been as high.

Economists that have analyzed Nebraska tax plans in the past have commented on the static and dynamic differences in the state’s sales tax:

“For example, a static estimate of a cut in the sales tax, say from 5 percent to 4 percent, would cause revenues to fall by 20 percent (= 5 – 4)/5). A dynamic estimate would show a smaller drop in revenue because it would capture the positive effect on the tax base of the cut in the sales tax. The complete elimination of the sales tax would not enable any dynamic revenue effects for the tax itself, since the rate would be zero. However, businesses would have more money to make profitable investments in Nebraska, thus increasing investment and employment, incomes and retail sales which, in turn, boosts sales and property tax collections.”[21]

This means, in addition to new revenue the state may gain from expanding the sales tax base, some revenue it would potentially forgo by reducing the sales or property tax rate could be recouped by new economic activity that would not otherwise be realized under the state’s current high tax rates.

Conclusion

Many economists, policy advisors, and lawmakers agree that changes need to be made to the state’s sales tax law in order to enable Nebraska to achieve significant, sustainable tax reform. Where the disagreement comes is what the scope of those changes should be, and how much revenue should increase or decrease as a result of those changes. Hopefully, this policy study shed some light on the discussions and can help guide policymakers in making the best decision for reform.

The sales tax should apply to all final consumption to follow the tax principle of “economic neutrality.” Neutrality ensures that the tax will not interfere with economic decision-making any more than is necessary. More commonly, this is known as not picking winners and losers. It is not the role of the tax code to favor golf lessons over a new pair of shoes. It makes little sense to tax the purchase of a lawnmower but not tax the purchase of lawn care services that remove the need to own a mower.[22]

There have been several broadly accepted standards and observations about sales taxes by both economists and public finance experts that are worth restating:

- Sales taxes should be imposed on all final consumer purchases of goods and services alike while exempting business inputs to avoid double taxation through tax pyramiding;

- The sales tax is more economically efficient than many competing forms of taxation, including the income tax, because it only falls on present consumption;

- Because lower-income individuals have lower savings rates and consume a greater share of their income, the sales tax can be regressive, though broadening the base to include additional consumer services and reducing the tax rate represents a progressive change; and

- Consumption is a more stable tax base than income, though the failure to tax most consumer services is leading to a gradual erosion of sales tax revenues.

Nebraska is at a time of great change, and with property taxes being the number one frustration for many Nebraskans, leaders are increasingly looking to the sales tax as a part of that change. Reducing reliance on the property tax through ending Nebraska’s many sales tax exemptions can help create the right environment for revenue-neutral tax reform that improves the state’s overall tax climate.

Changes to the sales tax can not only help alleviate other burdensome taxes but modernize Nebraska’s tax code and create a tax system that is beneficial to future generations. Tax laws need to adapt to a changing economy while also being pro-growth; promoting entrepreneurship and job creation. If these end goals are at the forefront of tax reform discussions, Nebraska will be on the path to greater prosperity.

Appendix 2: State Grocery and Drug Sales Tax Exemptions

|

State Sales Tax Rates and Grocery & Drug Exemptions |

|||||

|

(As of January 1, 2019) |

|||||

|

|

EXEMPTIONS |

|

|||

|

State Tax Rate |

Groceries |

Prescription Drugs |

Nonprescription Drugs |

||

| ALABAMA |

4 |

Taxed |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| ALASKA |

none |

— |

— |

— |

|

| ARIZONA |

5.6 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| ARKANSAS |

6.5 |

1.5% Local Tax |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| CALIFORNIA ** |

7.25 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| COLORADO |

2.9 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| CONNECTICUT |

6.35 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| DELAWARE |

none |

— |

— |

— |

|

| FLORIDA |

6 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Exempt |

|

| GEORGIA |

4 |

Exempt; Local Tax |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| HAWAII |

4 |

Taxed* |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| IDAHO |

6 |

Taxed* |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| ILLINOIS |

6.25 |

1% |

1% |

1% |

|

| INDIANA |

7 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| IOWA |

6 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| KANSAS |

6.5 |

Taxed* |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| KENTUCKY |

6 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| LOUISIANA |

4.45 |

Exempt; Local Tax |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| MAINE |

5.5 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| MARYLAND |

6 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Exempt |

|

| MASSACHUSETTS |

6.25 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| MICHIGAN |

6 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| MINNESOTA |

6.875 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Exempt |

|

| MISSISSIPPI |

7 |

Taxed |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| MISSOURI |

4.225 |

1.225% |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| MONTANA |

none |

— |

— |

— |

|

| NEBRASKA |

5.5 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| NEVADA |

6.85 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| NEW HAMPSHIRE |

none |

— |

— |

— |

|

| NEW JERSEY |

6.625 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Exempt |

|

| NEW MEXICO |

5.125 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| NEW YORK |

4 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Exempt |

|

| NORTH CAROLINA |

4.75 |

Exempt; Local Tax |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| NORTH DAKOTA |

5 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| OHIO |

5.75 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| OKLAHOMA |

4.5 |

Taxed* |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| OREGON |

none |

— |

— |

— |

|

| PENNSYLVANIA |

6 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Exempt |

|

| RHODE ISLAND |

7 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| SOUTH CAROLINA |

6 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| SOUTH DAKOTA |

4.5 |

Taxed* |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| TENNESSEE |

7 |

4% Local Tax |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| TEXAS |

6.25 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Exempt |

|

| UTAH |

5.95 ^ |

3.0% ^ |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| VERMONT |

6 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Exempt |

|

| VIRGINIA |

5.3 ^ |

2.5% ^ |

Exempt |

Exempt |

|

| WASHINGTON |

6.5 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| WEST VIRGINIA |

6 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| WISCONSIN |

5 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| WYOMING |

4 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Taxed |

|

| DIST. OF COLUMBIA |

6 |

Exempt |

Exempt |

Exempt |

|

| Source: Compiled by Federation of Tax Administrators from various sources. | |||||

| *Allow a rebate or income tax credit to compensate poor households | |||||

| ^ Includes statewide 1.0% tax in Virginia and 1.25% in Utah levied by local governments. | |||||

| ** Tax rate may be adjusted annually according to a formula based on balances in the unappropriated general fund and the school foundation fund. | |||||

References

[1] Walczak, Jared. (June 2019). Modernizing Utah’s Sales Tax: A Guide for Policymakers. Page 14. Retrieved from Tax Foundation: https://files.taxfoundation.org/20190611134106/Modernizing-Utahs-Sales-Tax-A-Guide-for-Policymakers-PDF.pdf.

[2] Cammenga, Janelle. (2019, January 30). State and Local Sales Tax Rates, 2019. Retrieved from Tax Foundation: https://taxfoundation.org/sales-tax-rates-2019/.

[3] Lock, B. (2009, December 1). Response to LR161, LR166, LR97 [Letter to Members of the Committee on Revenue], http://govdocs.nebraska.gov/epubs/L3770/B042-2009.pdf. Published in response to LR 161 introduced by Senator Abbie Cornett, Chair, and the members of the Revenue Committee. The report is also intended to address issues raised by LR 166, introduced by Senator Cap Dierks, the Revenue Committee Vice Chair, and the sales tax issues raised in LR 97, introduced by Senator Richard Pahls.

[4] Henchman-Bishop, J., & Drenkard, S. (2013). Building on Success: A Guide to Fair, Simple, Pro-Growth Tax Reform for Nebraska (pp. 29-33, Publication). Washington, D.C.: Tax Foundation. https://files.taxfoundation.org/legacy/docs/building_on_success_nebraska.pdf.

[5] McClelland, Harold, F. (1962, November). State and Local Finance, A Report of the Nebraska Legislative Council Committee on Taxation, Nebraska Legislature, page 429.

[6] Nebraska Department of Revenue, Chronological History of Nebraska Tax Rates, History of Nebraska Income Tax and Sales Tax Rates Through 1992 and Nebraska Tax Rate Chronologies Table 1-Income Tax and Sales Tax Rates, http://www.revenue.nebraska.gov/research/chronology/history.pdf and http://www.revenue.nebraska.gov/research/chronology/4-607table1.pdf.

[7]Nebraska Department of Revenue, Title 316 , Chapter 9-Local Sales and Use Tax, REG-9-004 AUTHORIZATION FOR COUNTIES, http://www.revenue.nebraska.gov/legal/ regs/localopt.html#004.

[8]Nebraska Department of Revenue, Title 316, Chapter 9-Local Sales and Use Tax, REG-9-002 AUTHORIZATION FOR CITIES – UP TO 1½%, http://www.revenue.nebraska. gov/legal/regs/localopt.html#003.

[9] Nebraska Department of Revenue, Local Sales and Use Tax Rates Sorted by Rate: Effective April 1, 2019. http://www.revenue.nebraska.gov/question/sales_ratesort.html#per2.

[10] Dakota county residents approved their sales tax via a referendum. Gage county was added via LB472-2019 by the legislature as a way for the county to pay for a $28.1 million legal settlement for the wrongfully convicted 1985 Beatrice murder.

[11] St. Louis Federal Reserve, “Table 2.3.5 Personal Consumption Expenditures by Major Type of Product: Quarterly”, accessed July 23, 2019.

[12] Bureau of Economic Analysis, Total personal consumption expenditures by state (Nebraska), last updated October 4, 2018 using 2017 figures.

[13] Walczak, Jared. (2016, August 18). A Twenty-First Century Tax Code for Nebraska. Retrieved from Tax Foundation: https://taxfoundation.org/twenty-first-century-tax-code-nebraska/#_ftn20.

[14] Facts and Figures 2019: Howe Does Your State Compare. “Table 22 State Sales Tax Breadth Fiscal Year 2017”. Retrieved from Tax Foundation: https://files.taxfoundation.org/20190715165329/Facts-Figures-2019-How-Does-Your-State-Compare.pdf.

[15] Henchman, Joseph; Drenkard, Scott. (2013 October). Building on Success: A Guide to Fair, Simple, Pro-Growth Tax Reform for Nebraska. Retrieved from Tax Foundation: https://files.taxfoundation.org/legacy/docs/building_on_success_nebraska.pdf.

[16] Data was collected from the Department of Administrative Services’ Annual Budgetary Report.

[17] Cordato, Roy (2018). Tax Reform, Retrieved from John Locke Foundation: https://www.johnlocke.org/policy-position/tax-reform/.

[18] Robertson, Gary D. (2019 May 6). NC collections may surge $700M above projections. Retrieved from AP News: https://www.apnews.com/1c50ec2595cd43079bc2983bc1112201.

[19] Mullahy, Brain (2019 May 15). Opponents of controversial Utah tax reform say it’s too much, too fast. Retrieved from KUTV: https://kutv.com/news/local/opponents-of-controversial-utah-tax-reform-say-its-too-much-too-fast.

[20] Department of Administrative Services, 2018 Nebraska Annual Budgetary Report.

[21] Tuerck, David G.; Head, Michael; Conte, Frank. (2015 January 27). Strong Roots Nebraska and LB357: Growing Nebraska with Sensible Tax Relief. Platte Institute and The Beacon Hill Institute at Suffolk University. Retrieved from the Platte Institute: https://www.platteinstitute.org/research/detail/strong-roots-nebraska-and-lb357-growing-nebraska-with-sensible-tax-relief.

[22] Walczak, Jared. (June 2019). Modernizing Utah’s Sales Tax: A Guide for Policymakers. Page 14. Retrieved from Tax Foundation: https://files.taxfoundation.org/20190611134106/Modernizing-Utahs-Sales-Tax-A-Guide-for-Policymakers-PDF.pdf.