Get Real About Property Taxes, 2nd Edition

Summary: Get Real About Property Taxes, 2nd Edition

Table of Contents

(Click a link to read a section of the report)

Nebraska Property Tax Reform Timeline

Nebraskans’ Views on Property Tax Reform

A 21st Century Sales Tax for Nebraska

Economic Development and Business Incentives

Property Tax Reform Options in Summary

Appendix: Property Tax Reform Polling Responses

It’s time to get real about property taxes in Nebraska.

Property taxes are undoubtedly the best-known and most hated tax in the state. But Nebraskans are affected by property taxes in many different ways, creating several barriers to reform that policymakers must address to arrive at any solution.

One obvious barrier is the Nebraska Legislature itself. Though high property taxes dominate the discussion in the Unicameral, a simple majority vote from state senators is not sufficient to pass property tax reform legislation. Without a 33-vote consensus that can overcome a legislative filibuster, no major reforms will be enacted.

State senators or legislative procedure don’t deserve all of the blame, though. After all, senators rely on the input of their constituents, who often make contradictory demands for lower taxes and more spending on government services.

Another barrier facing lawmakers is that the state itself does not collect the property tax, which is a local tax in Nebraska. Still, they are expected to solve the problem to the satisfaction of property taxpayers, the local taxing subdivisions that collect property taxes, and those who desire the state to fund other programs or state tax policy changes. It is difficult to do anything that will make all of these groups happy.

While it may seem obvious that one way to lower property taxes would be to require local property taxing subdivisions to cut spending and do with less, many of their responsibilities are mandated by the state and federal government.

School districts must provide all children in their community access to an education. Counties and other local governments must provide for a justice system, roads, and services such as police, fire, and emergency medical services.

In recent years, the state has increased spending on the property tax problem, subsidizing property taxes with state sales and income tax dollars. But the fundamental tax structure has not changed, and as property tax valuations have risen, these programs have been ineffective in curbing tax increases.

Anything the state does to address property tax comes with a cost to someone. If the state mandates a lower property tax levy rate, a cap on assessment growth, or makes a change to property valuations, that will come at a cost to local subdivisions, who will lose revenue for providing local services.

If the state replaces those revenues from property taxes with other funds from sales and income taxes, that will come from the taxes Nebraskans would otherwise pay for services provided by the state.

As discussed in previous reports, the state’s flexibility has been limited by slower revenue growth resulting from a downturn in agriculture. The Legislature has to balance spending on programs supported by the state, such as Medicaid, corrections, and higher education, with funding for services that are otherwise funded by property taxes, such as public schools.

This paper intends to report on which tax policy changes have the best chance of working to achieve lasting property tax reform. Policy studies tend to gloss over the difficulty of making such big changes. This report will not.

This study also asks whether Nebraskans themselves are ready for changes that could realistically address the current property tax burden. We will investigate that question and look at responses to possible approaches through scientific polling of Nebraskans represented by the Legislature’s Revenue Committee.

Finally, even policymakers who do agree that property tax reform is an important policy issue disagree on how much the state can afford to spend to offset the property tax.

If policymakers wanted to pursue a major, immediate reduction in property taxes, or were forced to by a voter initiative, it would necessarily require the state to find more revenues. But this policy change is still fraught with danger for the state and for taxpayers. Without needed reforms to the structure of property taxes, the state could put itself on the hook for significant increases in spending and taxes, with no positive change to the local property tax burden.

After all, the state is now spending $275 million on direct subsidies for property taxes annually, while property taxes are higher than they’ve ever been. Getting real about property taxes means acknowledging that difficult, and even initially unpopular choices may be needed if lawmakers truly want to make the property tax less of a worry for Nebraskans.

History

Despite current dissatisfaction with property taxes, there have been multiple reforms to the tax in Nebraska’s history. Originally, Nebraska levied a state property tax. That changed in 1967, when the state’s property tax was abolished via constitutional amendment. Instead, the Legislature created the income and sales tax to fund state government.

Local governments were still allowed to levy a property tax to fund their operations, but with time, those property taxes became a problem as well.

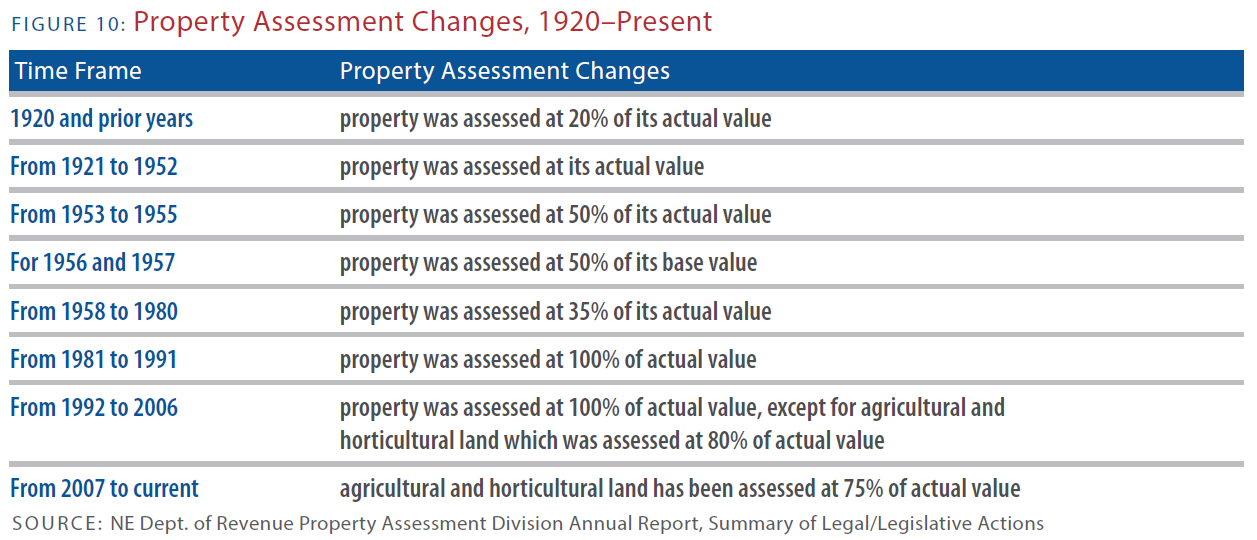

Following the constitutional amendment ending the state property tax, the first major change to the local property tax was in 1979, when the assessment level changed from 35 percent of actual value to 100 percent of actual value.1 This means the entire market value of property was subject to the property tax rate, instead of only a fraction.

The next big change to the property tax was addressing how to fund K–12 education. This became an issue because schools are the most expensive function of local governments, and today, the school district levy makes up 60 percent of the total property tax levied.2 In the 1980s, school district levies ranged from less than $0.45 to over $3.40 per $100 of assessed value, and over 70 percent of the cost of operating public schools was from the property tax.3 The state’s current school funding formula, also known as LB1059 or TEEOSA, was signed into law in 1990.

The debate around TEEOSA focused on the question of “how we fund education and how we tax property.”4 As one senator put it, “the first goal (of TEEOSA) was to try and shift the burden of taxes in this state from property to sales and income [and] do away with the overreliance on property taxes.”5 One of the key points of opposition to the bill was that school districts that were currently receiving funds from the state would lose that revenue, because the new formula still viewed property ownership as the “only indicator of wealth.”6 This argument still holds today.

Critics of the formula note that most school districts do not receive equalization aid (one of several sources of state aid) due to their higher agricultural land values, while a smaller group of mostly urban school districts receive most of the equalization aid.

Initially, however, the enactment of TEEOSA led to additional state funding being directed to schools, and the state dropped the maximum school district levy limit to $1.10.

Another significant property tax relief effort was LB1114 and LB299 in 1996. These laws placed a limit on local government expenditures7 and levy limits on the total property tax rate. The rate decreases took effect in 1998 and again in 2001.8 The discussion of county consolidation or the consolidation of local governments was also discussed in 1996 as a property tax relief measure. The result was a constitutional amendment ballot initiative to provide the Legislature the authority to establish methods for counties to merge with other counties or cities. The question was placed on the 1996 general election ballot, and it failed to pass by a margin of 47 percent (for) to 53 percent (against).9

Targeting relief towards agricultural land has also been a method used to reduce property taxes. In 1992, the assessment of agricultural land was lowered to 80 percent of its actual value, and then reduced again to 75 percent in 2007. The Property Tax Credit Fund was created in 2007. Under this program, state money from sales and income tax revenue is sent to local taxing subdivisions, which appears as a credit on local property tax bills. The program started at a state cost of $105 million and has grown to $275 million in the last fiscal year.10

What history has shown us is that while property taxes are now only locally levied, there is significant state involvement with the amount of tax local political subdivisions can levy, how property assessments are conducted, and what services local taxing subdivisions must provide for their residents. Many of the changes the state has made in the past to lower the local property tax required a shift in financial responsibility from the local governments to the state. This comes at a cost to state taxpayers, because the state has obligations it must fund as well, with a limited amount of state tax dollars.

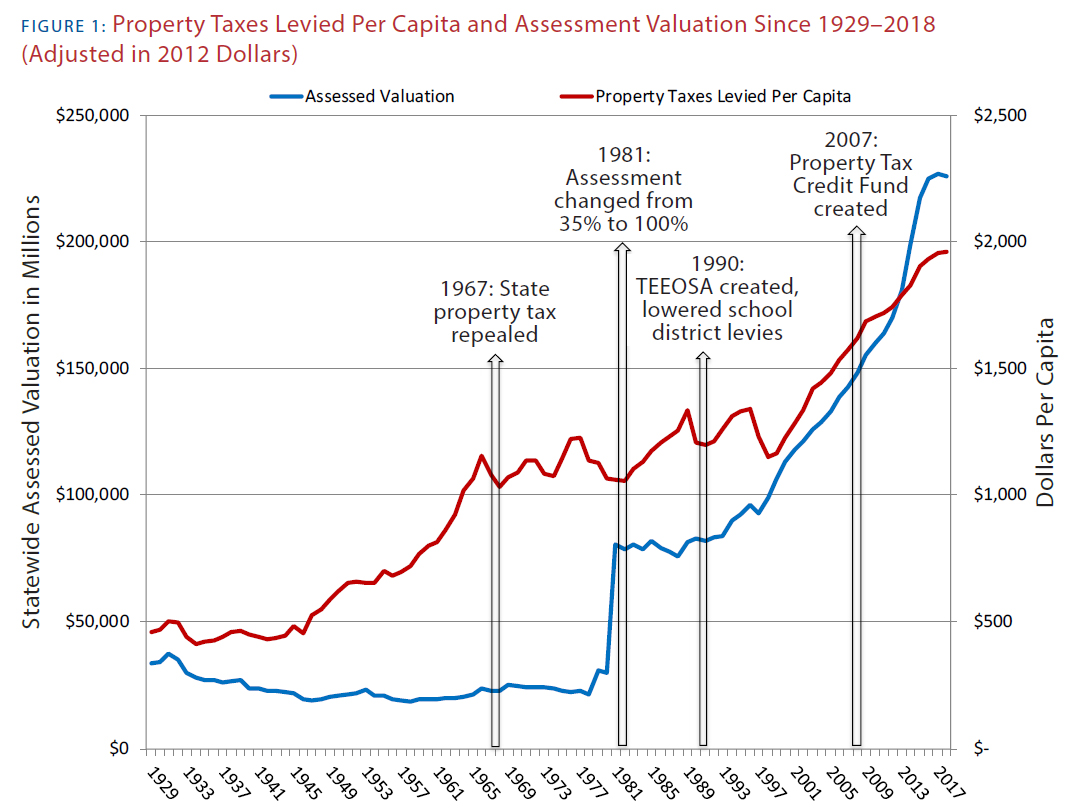

The state’s ability to address the property tax problem is not only limited by tax revenues and the state’s economic circumstances. Crafting a policy that actually restrains the growth of property taxes also appears to be a historical problem. On a per capita, inflation-adjusted basis, property tax collections in Nebraska have never been higher than they are today (see Figure 1). The growth of these taxes has not been reined in, either with higher state taxes and more spending, or previous attempts at reductions in levy rates or the agricultural assessment ratio.

Some would argue the state has not yet spent enough to offset the property tax. However, even in parts of Nebraska where taxing subdivisions receive the largest amounts of financial support from the state, property taxes are well above the national average. This means a proper combination of both spending and limitations on property taxing authority will be needed to secure lasting property tax reform.

1857 Property tax adopted by the Territorial Legislature.

1867 Nebraska gains statehood. State and political subdivisions begin levying property taxes.

1920 New revenue law passes to assess real property at actual value instead of 20% of actual value.

1953 Property assessment changes to 50% of actual value.

1954 Voters approve constitutional amendments on property values, methods of determining uniform value, and prohibiting a state property tax if the state ever adopts a sales or income tax.

1956 Property assessment changes to 50% of base value.

1958 Voter approve constitutional amendment to cancel property taxes and assessment charges unpaid for 15 years.

1966 Ballot initiative to limit state property tax fails, while voters approve a constitutional amendment to terminate the state property tax.

1967 State property tax is abolished. Legislature creates state income taxes and sales tax as replacement revenue sources for state government.

1968 Ballot initiative to classify or exempt personal property from taxation fails.

1969 Homestead exemption program created.

1972 Voters pass constitutional amendment allowing agricultural and horticultural land to be valued based on its current use, rather than potential use.

1978 Voters approve constitutional amendment for the state board of equalization to equalize assessments of property among counties.

1980 Voters reject constitutional amendment to require “a system of financing public education that imposes no unfair and excessive property tax burden.”

1981 Property tax assessment changes from 35% to 100% of actual value.

1984 Nebraska Supreme Court case, Kearney Convention Center Inc. v. Board of Equalization, holds the State Constitution’s uniformity requirement demands agricultural land be assessed similarly to other classes of property, at full market value.

The State Constitution is then amended to make agricultural and horticultural land a distinct class of property.

1988 The U.S. Court of Appeals case, Trailer Train v. Leuenberger, prohibits personal property tax collections from railroads.

1989 The Nebraska Supreme Court rules, in Northern Gas v. State Board of Equalization, that pipelines, telephone companies, and other centrally assessed entities should be treated the same as railroads.

1990 TEEOSA (LB1059) caps school district levy rates to $1.10 and increases state income and sales tax rates.

Voters approve constitutional amendment to remove agricultural and horticultural land from the uniformity clause, requiring this land to be assessed uniformly only within its own class of property.

1991 The Nebraska Supreme Court rules, in MAPCO Ammonia Pipeline v. State Board of Equalization, that all prior personal property exemptions were unconstitutional, thus reversing earlier cases.

1992 Agricultural and horticultural land is assessed at 80% of actual value.

Voters approve constitutional amendment establishing separate and uniform tax valuation of tangible personal property.

1995 Tax Equalization and Review Commission (TERC) formed. Body hears valuation appeals and exemption disputes instead of district courts.

1996 LB1114 places a limit on local government expenditures and reduces levy rates in phases.

Ballot initiative providing for the Legislature to consolidate counties fails.

1997 LB271 changes the taxation of motor vehicles to be different than taxation of other property.

1998 1996 property tax limitations fully implemented, limiting local governments to tax levy rates of no more than $2.19 per $100 of property value.

Voters approve constitutional amendment to exempt government property used for public purposes from taxation.

1999 Department of Property Assessment and Taxation created as a separate state agency, distinct from the Department of Revenue. Administrator appointed by the governor for a six-year term.

2003 LB540 lowers school district levy limit to $1.05, the current amount.

2004 Voters approve constitutional amendment exempting certain improvements of historically significant real property from property taxation.

2005 Nebraska Advantage Act is created, offering property tax exemptions to companies in the state that meet certain employee and capital investment goals.

2006 LB968 prevents reduction of school district levy lid to $1.00.

Maximum exempt amount and maximum value for homestead exemption increased.

Assessment of agricultural and horticultural land reduced to 75% of actual value, and changes from income valuation to market valuation. This policy is still in use today.

LB 808 eliminates agricultural zoning requirements, but clarifies that the entire parcel must be used for agricultural or horticultural purposes in order to receive special valuation.

Legislature authorizes Learning Community taxing subdivision for Douglas and Sarpy Counties with a common school levy rate of $0.95.

2007 LB367 creates the Property Tax Credit Act at a state cost of $105 million.

The Department of Property Assessment and Taxation is returned to the Department of Revenue, and the Property Tax Administrator functions within the Department of Revenue.

2008 An exemption for tangible personal property is established in Nebraska’s Beginning Farmer Tax Credit Act.

LB 777 excludes land associated with buildings from the parcel of agricultural and horticultural land and clarifies the rest of the parcel can qualify for the special valuation if it meets other requirements.

Property Tax Credit Act increased to $115 million.

2009 Legislature passes LB121, requiring all counties to resume assessments before June 2013. Previously, some counties turned over assessment responsibilities to the state.

2010 Tax exemptions for property used in wind generation enacted.

2012 Tax exemptions for data center property enacted.

Community College levy lid increases to $0.1025, its current rate.

2014 Income limitation amounts for homestead exemption increased.

Property Tax Credit Act increased to $140 million.

2015 Property Tax Credit Act increased to $204 million.

2016 LB958 increases the Property Tax Credit Act to $224 million and directs the additional $20 million towards agriculture.

LB1067 eliminates common school levy in Learning Community school districts.

2019 LB103 created an automatic lowering of the levy rate if valuations increase.

Property Tax Credit Act increased to $275 million.

Nebraskans’ Views on Property Tax Reform

Despite all the reform attempts made by the state over the last fifty years, Nebraskans remain concerned about property taxes. Nonetheless, synthesizing these concerns into an understandable consensus can be difficult.

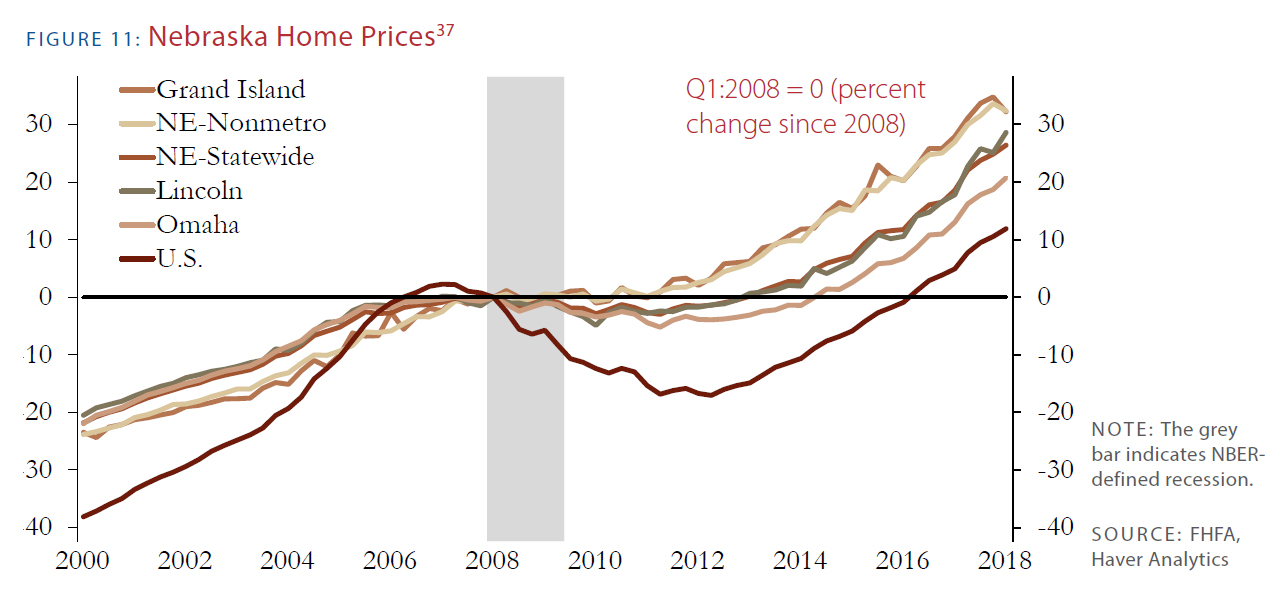

Agricultural land values increased substantially over the last decade as commodity prices reached record highs. Though the pace of growth for residential property owners was less by comparison, a report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City finds that home values in Nebraska have grown the sixth fastest nationally in the same period of time (See Figure 11). That means farmers, ranchers, and landowners are disproportionately impacted by even modest increases in property tax rates. But property tax rate hikes that may seem small to homeowners now may not seem so manageable as more updated assessed valuations arrive.

Local school districts are not unanimous on how the property tax issue should be addressed, either. Districts currently receiving equalization aid have opposed changes to the education funding system that would create a base amount of education funding for each student enrolled in public schools and place greater limits on property taxing authority, while un-equalized districts support these reforms. Taxpayers are also divided. Even those concerned with property taxes may believe property tax reform will impose too great a cost from other types of taxes they pay to state or local government. For example, some taxpayers may feel overburdened by state income taxes, or feel that taxes they pay to the state will not find their way back to the local community and result in property tax reductions.

Some parts of the state may not have the needed mix of taxpayers to collect their own revenues to offset high property taxes, making them dependent on the state for a policy fix. And, undoubtedly, some Nebraskans are accustomed to the state’s high property taxes and feel the levies are validated by the amenities, services, and public employment opportunities their revenues make available in our communities.

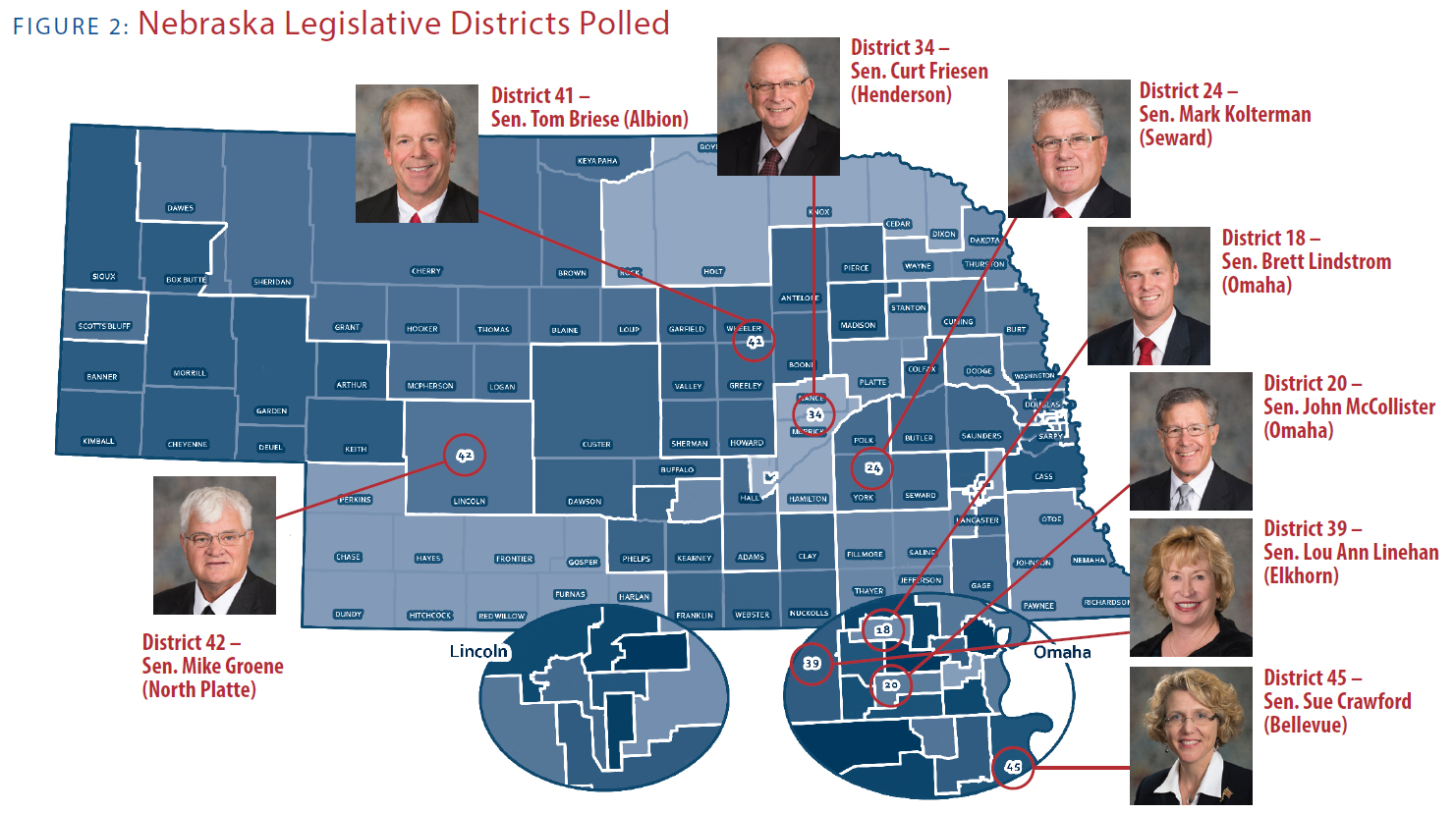

In an effort to collect and better understand these various views, the Platte Institute conducted a scientific poll in January 2019, which received 2,977 responses. The respondents were likely voters residing in eight state legislative districts represented by senators serving on the Nebraska Legislature’s Revenue Committee in the 2019 session. Their answers may give us a better sense of what Nebraskans mean when they say, “property tax relief.”

The complete set of polling responses can be found in the appendix.

Regardless of a candidate’s proposed policy approach to the issue, it is good politics to run for the Nebraska Legislature on a platform of reducing local property taxes. In practice, however, the need to make difficult choices about changing taxes or spending has prevented senators from reaching a solution that significantly and sustainably reduces the property tax burden.

Our polling results can give us insight into why that may be.

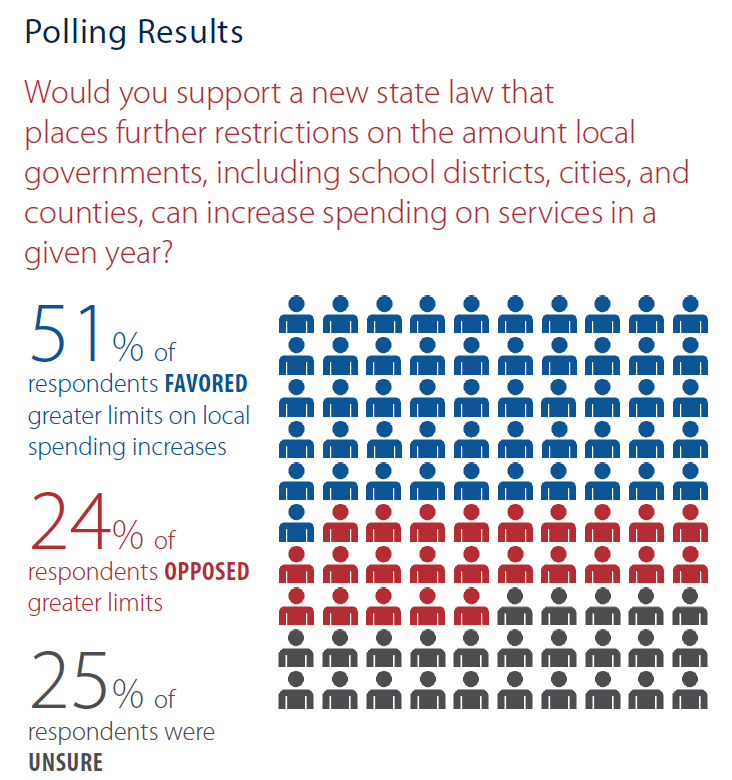

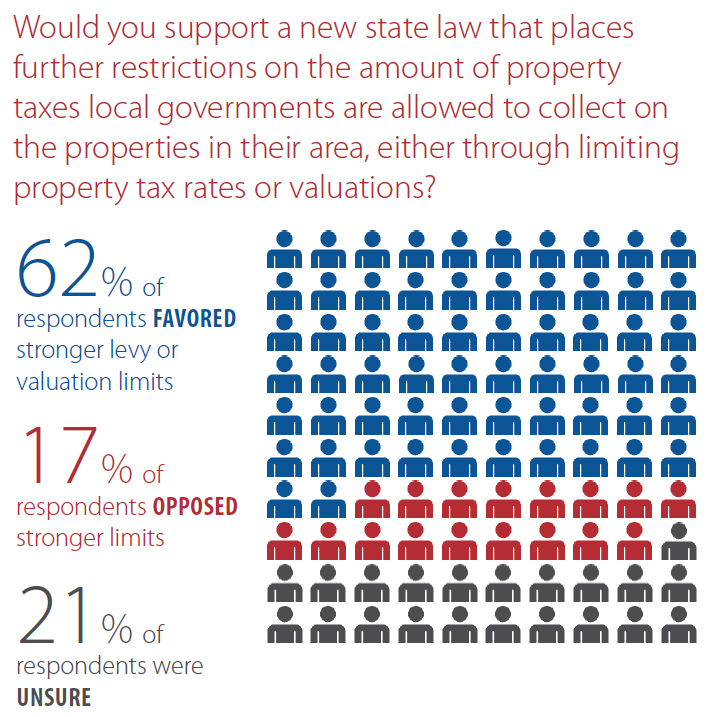

Nebraskans may be divided on many aspects of property tax policy, but voters across the political spectrum respond favorably to proposals to limit local property taxing authority. Our first question on property tax limitations asked: “Would you support a new state law that places further restrictions on the amount local governments, including school districts, cities, and counties, can increase spending on services in a given year?”

Overall, 51% of voters favored greater limits on local spending increases, 24% were opposed, and 25% were unsure. A stronger spending limit was the most favored option in every district. Republicans and Independents were more likely to favor a stronger spending limit than Democrats in each district, but Democrats also favored the proposal in 3 of the 8 districts. In addition, respondents were asked if they would favor a new law placing more limits on how local governments could levy property taxes: “Would you support a new state law that places further restrictions on the amount of property taxes local governments are allowed to collect on the properties in their area, either through limiting property tax rates or valuations?”

This proposal won strong majority support across the state. In all, 62% of voters favored stronger levy or valuation limits, 17% opposed the change, while 21% were unsure. Notably, at least a plurality of Republicans, Democrats, and independents all favored this policy in 7 of the 8 polled districts. In District 42, which is in Lincoln County, a total of 70% of all voters polled favored additional property tax limits, including 69% of Republicans, 68% of Democrats, and 75% of independents.

In the only district where more Democrats opposed the limits than favored them, the difference between support and opposition was only two percentage points, or within the margin of error.

These numbers reflect once again that calling for property tax cuts makes for very good politics in Nebraska among voters of all political viewpoints, and that voters are receptive to some key policy ideas that could work.

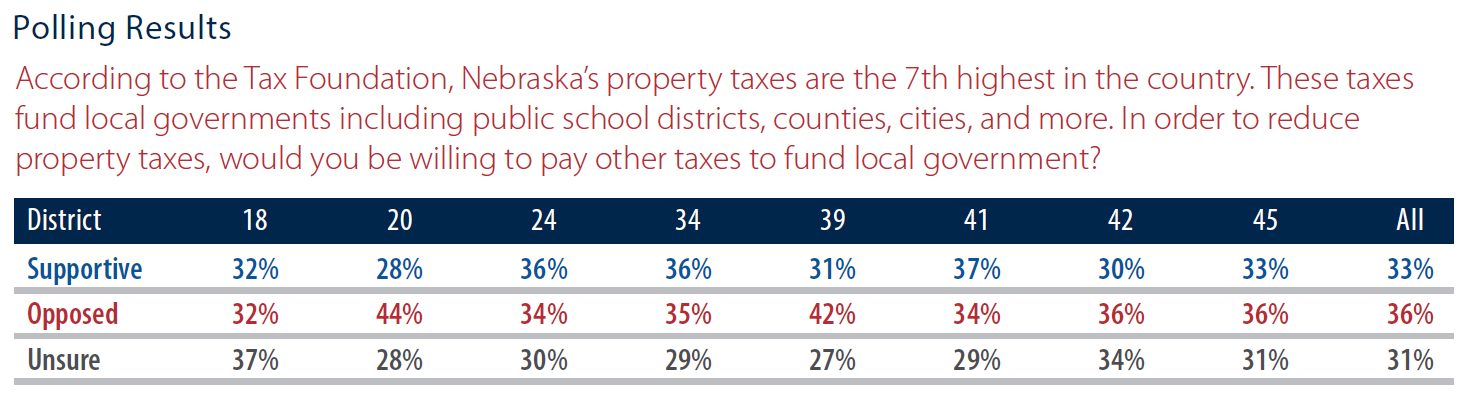

But since it’s unlikely that the Legislature will simply cut tax levies and valuations without providing additional funds to impacted local governments, it’s also necessary to ask what voters think about the cost of raising new revenues. We directly asked these voters their opinion about this possibility. Our question was: “According to the Tax Foundation, Nebraska’s property taxes are the 7th highest in the country. These taxes fund local governments including public school districts, counties, cities, and more. In order to reduce property taxes, would you be willing to pay other taxes to fund local government?”

As with the previous questions, voters were offered the chance to state that they were unsure about their answer. This factor contributed to none of the options earning a clear majority, and voters were far less certain about this aspect of property tax reform than limiting spending growth, or reducing tax levies and valuations.

Thirty-six percent of respondents opposed paying other taxes to reduce property taxes, while 33% supported a tax shift. Another 31% were unsure. The results are divided by district below. While the largest number of voters expressed opposition to paying other taxes, the difference was within the margin of error in 5 of the 8 districts.

It is worth noting that no specific type of tax was mentioned in this poll question. Different voters may imagine different types of taxes to be raised or changed to carry out the proposal. In a previous unscientific Platte Institute survey, a majority of respondents indicated a willingness to pay additional sales taxes as a way to reduce property taxes. No other tax type received majority support.

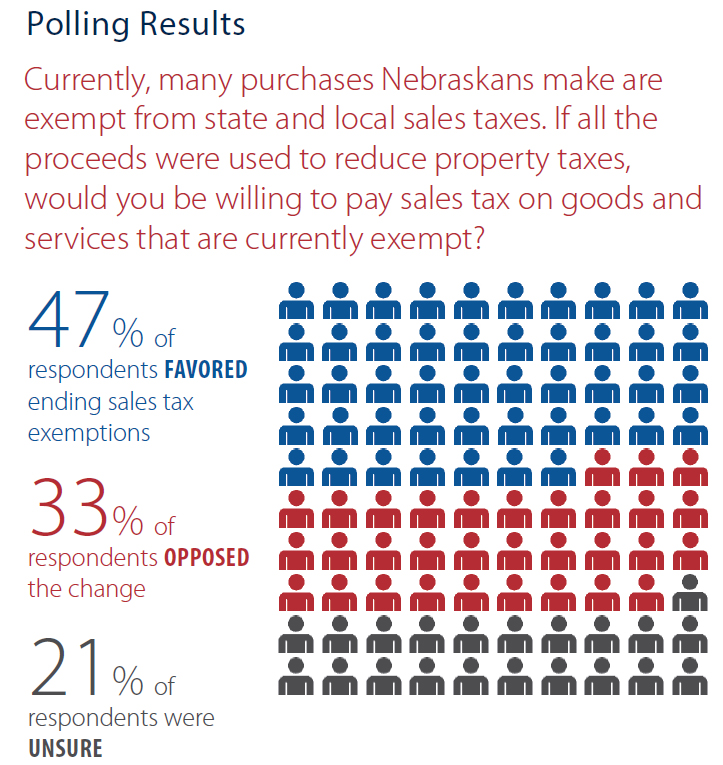

We decided to give more specificity to the subject of a potential tax shift by asking what voters thought of removing sales tax exemptions as the primary means of property tax reform. In our next polling question, we asked: “Currently, many purchases Nebraskans make are exempt from state and local sales taxes. If all the proceeds were used to reduce property taxes, would you be willing to pay sales tax on goods and services that are currently exempt?”

Voters were significantly more receptive to paying sales tax on exempt goods and services to reduce property taxes than they were to an open-ended tax shift. Overall, 47% supported ending sales tax exemptions, 33% opposed the change, and 21% were unsure.

Expanding the sales tax to include exempt goods and services won the top spot in all eight legislative districts, including in District 39 in western Douglas County, where a high of 56% of voters favored the proposal.

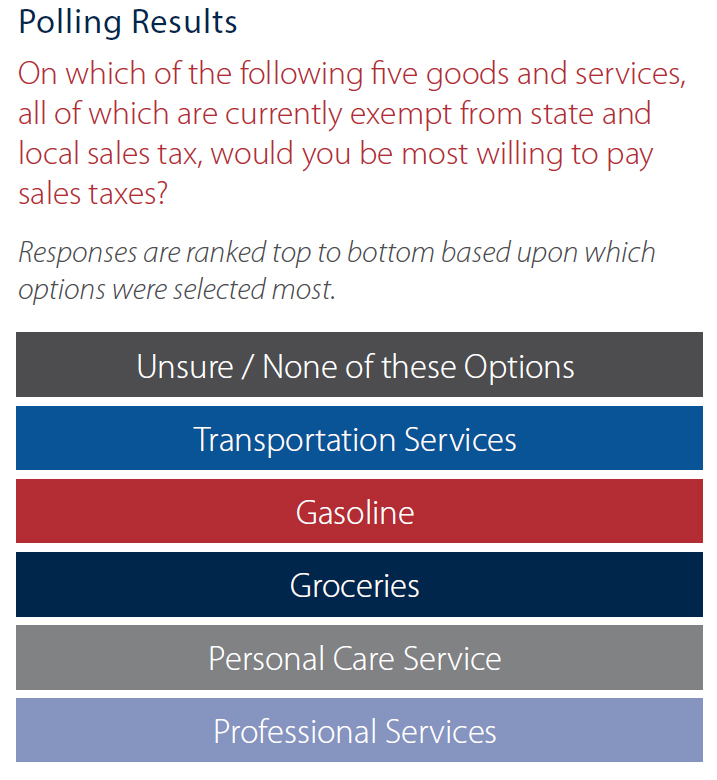

What we can gather from this result is that a lot of Nebraskans are at least receptive to the idea of eliminating sales tax exemptions as a means for reducing property taxes. They are clearly less hostile to the concept of using that revenue source to pay for local government services than other approaches that they might interpret as an unmitigated tax increase. Just as with our initial question of whether voters favor reducing local property tax authority, this response deserved to be vetted. In the following question, respondents were asked to provide more specifics. Five categories of goods and services that are frequently exempt from sales tax in Nebraska were provided to voters. Respondents were asked to select one category for which they would be most willing to pay sales tax.

The listed categories were:

• Personal care services, including haircuts, massages, and manicures;

• Professional services, including veterinary care, legal advice, or motor vehicle repair;

• Transportation services, including buses, taxis, limousines, and Uber or Lyft;

• Groceries;

• and Gasoline

Like the other questions, voters were given the ability to select that they were unsure, or that they chose none of the above options. Despite the initial support for removing sales tax exemptions, in all eight legislative districts, voters said they were either unsure which exemptions should be eliminated, or were unwilling to pay sales tax on any of the offered options.

The hierarchy selected by voters who did choose an exemption to eliminate was somewhat surprising. To this point, most legislative proposals to expand the sales tax base have relied heavily on the inclusion of more personal care services and professional services. Yet these choices were actually the least likely to be favored by respondents.

Sales taxes on transportation services, gasoline, and groceries were favored by more voters who selected an exemption to end than other services. Typically, imposing sales tax on staples like food and motor fuel is considered unthinkable by many policymakers.

On the whole, though, these results illustrate yet another barrier that makes the job of property tax reform much easier said than done for elected officials. It may be the case that given the choice, no one would wish to pay sales tax on a haircut, legal services, a taxi ride, a tank of gas, or a bag of groceries.

But it is also the case, as we will discuss later, that the Legislature will be unable to achieve an immediate, major reduction in property taxes if taxpayers are unable to tolerate any of these changes at all.

Nebraskans have responded to past increases in property tax relief programs with little enthusiasm, which seems to suggest taxpayers have a much more significant desire for property tax reductions than the state has been able to deliver. But the difficulty will be whether leaders can communicate a vision that would make such a change both politically possible and economically feasible.

Voters currently have the opportunity to support a 2020 ballot initiative related to property taxes. It would amend the state constitution to create an income tax credit refunding 35% of local property taxes paid. A similar, though somewhat smaller proposal, was estimated by the Legislative Fiscal Office to cost up to $1.3 billion a year.

It is unlikely such an outlay of state money could be afforded without legislators making the previously discussed tax policy changes, or an enormous reduction in state spending.

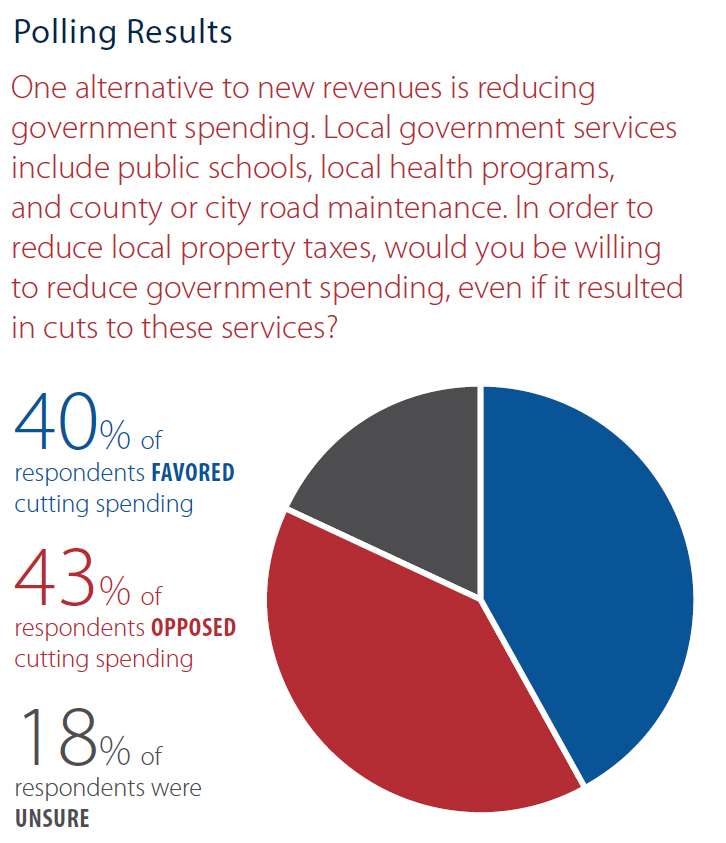

But in our scientific poll, voters were reluctant to support reductions in government spending to lower property taxes, especially voters in urban districts. We asked: “One alternative to new revenues is reducing government spending. Local government services include public schools, local health programs, and county or city road maintenance. In order to reduce local property taxes, would you be willing to reduce government spending, even if it resulted in cuts to these services?”

Overall, 43% of voters opposed cutting spending, 40% supported cutting spending, and 18% were unsure.

Opposition was much more pronounced in Omaha Metro area districts. A majority of voters opposed cutting spending for property tax reduction in Districts 18 and 20, and a plurality opposed cuts by ten percentage points in District 45. Alone among Omaha area districts, the more suburban and rural District 39 favored cutting spending, along with rural District 41. All other districts were tied or opposed (See Appendix).

While it may be unsurprising to hear that Republicans were more likely to favor cutting spending and Democrats strongly opposed it, the breakdown shows an even more nuanced picture. A majority of Republicans only favored spending cuts in two districts, and only by narrow majorities. In numerous districts, a combined majority of Republicans were opposed to cuts or unsure. That means a lot of Republicans are also susceptible to having second thoughts about whether property taxes are bad enough to justify cutting spending.

Supporters of cutting spending may argue that this polling question was asked in a way that was intended to make the choice difficult for voters, even conservative Republicans. They would be right. Ultimately, any effort to cut government spending will face enormous outcry from interest groups and the public that will temper any kneejerk reaction to simply cut budgets. Polling should reflect how Nebraskans might respond given those challenges.

The answers to these questions begin to paint a clearer picture of why Nebraska is in its current position. Voters are strongly confident about placing more restrictions on local property taxing entities, but they mostly don’t want government to cut spending to get there. They may be willing to pay certain types of taxes they’re not paying right now to bridge the gap, but that support could be fragile depending on how those changes are presented.

As previous reports have shown, the state is not currently generating enough new revenue on its own to provide a major reduction in property taxes out of pocket, particularly as new demands for spending arise every year at the local level. This stark reality demands for taxpayers to get more specific, and their leaders along with them: if they want very significant property tax reductions, how are they willing to pay for them?

Consistent with our polling, in 2019, the Legislature’s Revenue Committee appeared to reach a consensus that sales tax was the most desirable revenue source for offsetting local property tax. The desirability of the sales tax may relate to a feeling that it is more voluntary or within the control of the taxpayer than property or income tax. Income is taxed as it is earned, and property tax is levied with assessments that may change over time, while sales tax is only owed on the amount a taxpayer chooses to spend.

There is also an argument to be made that sales tax has a built-in consideration for the ability to pay, insofar as a person cannot have sales tax assessed on them if they do not have the money to spend in the first place. Let’s discuss how Nebraska’s sales tax works currently and how it could potentially function under property tax reform.

Sales Tax

A major replacement of property tax collections with sales tax revenue has already happened once before in Nebraska’s history. When the state abolished its property tax in the 1960s, one of the two new taxes implemented was the state sales tax. The tax was structured to focus on the final sale at retail of any item of tangible personal property or goods.

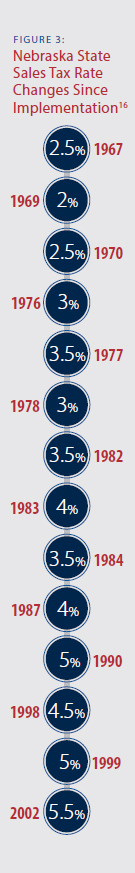

At the time, Nebraska was primarily a goods-based economy. Prior to the passage of the 1967 Sales Tax Act, the Legislature commissioned a study to focus on the design of a retail sales tax. This study recommended that business-to-business sales or business inputs be exempt, a structural principle that still exists in today’s law that is supported by economists as a sound tax policy.11 The original state sales tax rate was 2.5 percent. It has changed 13 times since then and is now 5.5 percent. Many Nebraska cities levy local sales taxes in addition to the state’s, placing the average combined sales tax rate in Nebraska at around 7 percent, though some cities are higher.

As a rule of thumb, all goods or tangible products are automatically subject to sales tax unless exempted by law. However, according to Nebraska’s tax expenditure report, there are 117 sales tax exemptions currently in state law, including many goods, like groceries, gasoline, or prescription drugs.12 Some of these exemptions date back to 1967 when the tax was created to exclude business inputs, while some were enacted as late as 2016, like the exemption for the purchase of fine art.13

Unlike most goods, which are subject to the sales tax, services sold to the final consumer are not taxed unless specifically mentioned in the sales tax law.14 This has become a problem because Nebraska has an increasingly service-based economy. Because services are mostly exempt from the sales tax, only one-third of what is purchased in Nebraska is now subject to the state and local sales tax.15 The exclusion of most services means that as the service sector grows, the amount of revenue the sales tax can bring in is being eroded. This narrow tax base is one reason why the sales tax rate has increased over time. As more of the economy is made up of nontaxable purchases, the rate must increase to collect the same amount of revenue.

One question Nebraskans and lawmakers have is whether the collection of sales tax from online transactions can broaden the tax base enough to enable significant property tax reform. This conversation accelerated in June of 2018, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the South Dakota v. Wayfair decision, allowing states to collect sales tax on out-of-state internet retailers. A previous ruling in the 1990s, dealing with catalog-based retailers, prohibited such collections.

In 2019, the Nebraska Legislature enacted Legislative Bill 284, which codified requirements necessary under the Wayfair ruling for the state to mandate the collection of sales tax from out-of-state internet retailers.

While some revenue will come to the state from the remittance of internet sales, it is hard to estimate the total impact to the state budget, since some retailers were already collecting voluntarily prior to the ruling. State estimates of how much new revenue will come in have varied greatly, but range in the tens of millions of dollars. Such a sum would not last long once split among Nebraska’s many property taxpayers. That means a broader source of sales tax revenue would be needed if fundamental property tax reform is the goal. Economists tend to agree that the least economically detrimental solution for broadening a sales tax is to end sales tax exemptions on final consumer purchases, whether goods or services, wherever possible.

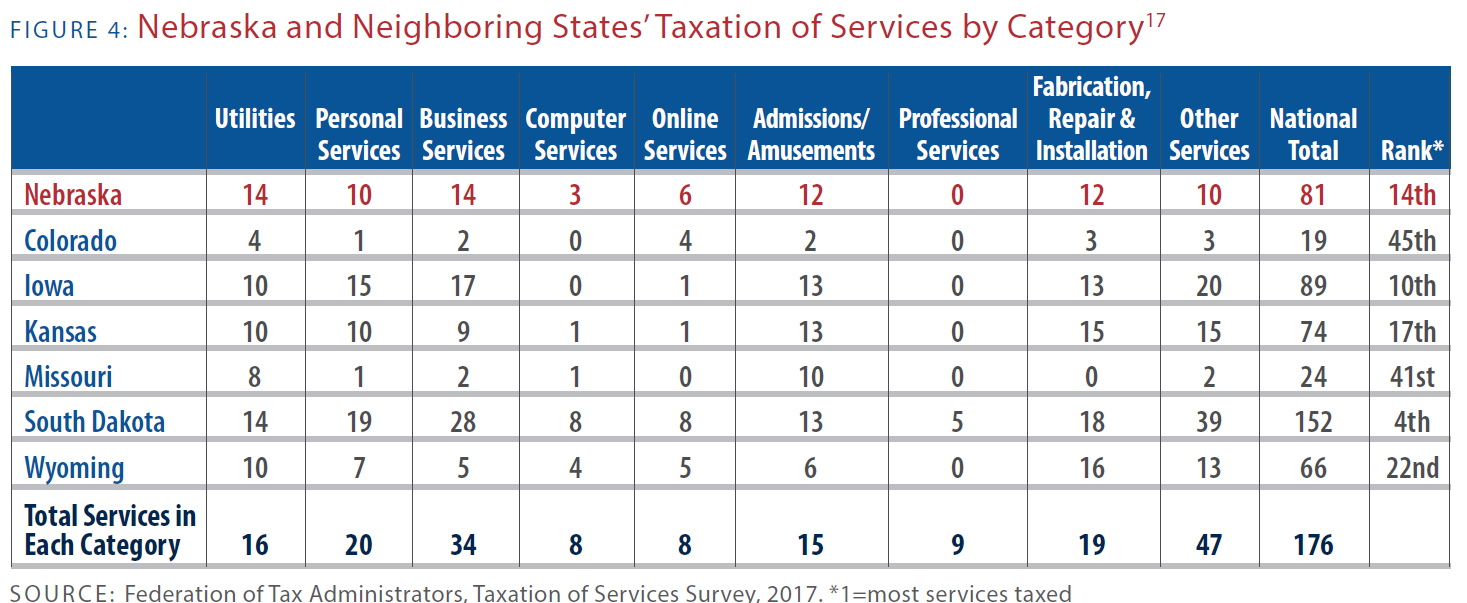

Besides increasing state and local revenue without increasing tax rates, expanding the sales tax base provides an added benefit for government budgets as well. A broader sales tax will make tax collections more reliable during economic swings, which will help the state to sustainably fund its commitment to property tax reform, and help local political subdivisions replace more of their property tax revenues with sales taxes if their taxpayers desire. One potential solution to enable this reform is highlighted in Figure 4.

In the economically ideal sales tax system, all consumer goods and services should be subject to the same tax rate. However, very few states come anywhere near achieving this ideal. Instead, political considerations often drive which goods and services are subject to sales tax, and at what rates.

Nebraska currently taxes 81 services and is ranked 14th nationally in the number of services taxed. While Nebraska is ahead of many states in this area, there is still plenty of room to improve. The top two states in the nation, Washington and Hawaii, tax 167 services.

Closer to home, South Dakota has the broadest sales tax base in our region, ranking 4th nationally for the number of services it taxes. It uses these revenues to forgo personal and corporate income taxes, as well as levying lower property and sales tax rates.

A 21st Century Sales Tax for Nebraska

In 2019, Nebraska state senators debated legislation to expand Nebraska’s sales tax to about 30 new goods and services. As ambitious as these proposals were, the policy was criticized from many possible angles.

Supporters of major property tax reductions could make a credible argument that the potential reductions in property tax would not be great enough to make a difference without other tax increases. Advocates for low-income residents would not be wrong to believe that paying new sales taxes at the state’s current tax rate would feel punitive for many taxpayers. And some business groups have a compelling argument that including some consumer goods and services but not others adds complexity to the tax code and is an example of government picking winners and losers.

Perhaps ironically, one of the only ways to effectively mitigate these concerns is to go even farther in ambitiously expanding the sales tax to more goods and services. Unless a fundamental reexamination of the sales tax is made, policymakers will always face insurmountable limits to addressing these competing concerns.

How do policymakers bridge the gap between tax research, which broadly supports the idea of collecting sales taxes on all final sales of consumer goods and services, and taxpayers, who often find paying sales tax on nearly all goods and services intolerable?

Tax reform is never easy. Property tax collections are a large sum paid by Nebraskans all across the state. To replace those revenues, lawmakers will need to look for sources that have a similarly broad base. Getting real about property taxes means coming to grips with the reality that there are very few palatable choices at the disposal of policymakers if they want to collect enough new, stable revenue to pay for significant and immediate property tax reforms.

Policymakers need to look at the sales tax as a tax meant to collect a sufficient share of the total consumer spending in the state economy. The good news of looking at the sales tax through this more expansive lens is that policymakers would still have ample control over how much sales tax Nebraskans should pay on their purchases.

As it stands, Nebraska’s roughly 7% combined sales tax applies to numerous goods and services that Nebraskans need in daily life, including utilities, over the counter medication, sanitary products, and many prepared foods that Nebraskans buy at the grocery store. It is worth noting that even if Nebraska taxed the sale of groceries again (as the state once did when the sales tax was first introduced), federal law prohibits sales of groceries purchased with SNAP or WIC nutrition benefits from being subject to tax. The fewer exemptions there are, the more revenue would be available to reduce the sales tax rate on all of these purchases, or to address other concerns legislators may have, in addition to property taxes.

However, because state senators have struggled to advance an overarching reform of Nebraska’s sales tax base, many property tax reform proposals have included an increase in the state sales tax rate.

In general, raising tax rates is less preferable than removing sales tax exemptions because it creates a greater financial burden on those who are currently paying the tax, while forgoing additional revenue from those who do not. A narrow tax base with a high tax rate can also make the tax less stable in times of economic uncertainty, or place Nebraska in a less competitive position with nearby states that have lower tax rates on the same goods and services.

It will likely take significant political will for senators to advance any proposal that involves these new revenues, since it faces boisterous opposition on all sides of the policy spectrum. A longer discussion of sales tax reform will be contained in Nebraska’s Sales Tax, a new Platte Institute report to be published at PlatteInstitute. org/Policy

Local Sales Tax

Another merit to expanding the sales tax base is its direct impact on locally collected taxes. Currently, cities and counties can levy their own sales tax with voter approval, and it can be set at ½, 1, or 1½ percent.18 Any city, except a metropolitan class city (Omaha), may impose a local sales tax rate up to 1¾, or 2 percent of the retail sales within the boundaries of the city.19 Currently, Dakota County and Gage County are the only counties authorized to have a sales tax.20

Twenty-seven cities levy a 2 percent tax, for a total state and local combined rate of 7.5 percent. The city of Lincoln is the only one to levy a 1¾ percent tax while a 1½ percent rate is levied by 112 cities. Ninety-seven cities have a local rate of 1 percent, and only two jurisdictions, Dakota County and Upland, have a local rate of ½ percent.21

If the state were to expand its sales tax base, local taxing subdivisions with sales tax authority would then receive additional revenue on each transaction that was newly subject to sales tax. This would increase the city or county’s sales tax collections, allowing for a proportionate reduction in their property tax through either a levy reduction or assessment reduction.

Many states allow their local governments to levy a local sales tax via voter referendum to fund local operations or projects. Nebraska should consider restructuring the local sales tax policy to better meet the needs of local taxing subdivisions, which may allow a lowering of local property taxes without putting a larger financial burden on the state.

Local option referendums are an important policy because the needs of communities differ across Nebraska. For example, if a policy such as a sales tax rate increase to replace property taxes is desired in Scotts Bluff County, but not Sarpy County, local policymakers would be able to better respond to those differences of opinion than the Legislature enacting a ‘one size fits all’ approach.

In legislative debate, cities and counties have been resistant to conceding property taxing authority, even when the possibility of greater sales tax revenue may be available to them. This reluctance may harken back to previous decades, when cities and counties saw their allowed property tax levies reduced by the state, and ultimately, lost all their direct sources of state aid.

For this reason, if municipal and county property tax reform is not possible, it may be worth asking whether local sales tax reform can be accomplished instead. If local sales tax rates are reduced in proportion to the increase of revenues from the removal of sales tax exemptions, that would help soften the blow of paying sales taxes on a wider range of goods and services for taxpayers, and would reduce the combined state and local sales tax rate.

There are also some complications with local sales taxes that prevent them from being fully utilized as an alternative to property tax. Currently, a county sales tax can only be imposed on taxable sales within the county, but not within the boundaries of any city that also imposes a city sales tax.22 In May of 2018, Dakota City voters approved a separate city-wide sales tax from their existing county tax. Per the Nebraska Department of Revenue, since Dakota City is within Dakota County, the county sales tax would no longer be effective for taxable sales made within the Dakota City boundaries.23

This small ½ cent city sales tax was intended to supplement infrastructure improvements without increasing property taxes, but an unintended consequence was that the county will no longer be allowed to apply sales tax to items sold within the city limits. This situation experienced by both Dakota City and Dakota County illustrates a deficiency in the current local option sales tax policy.

One possible reform could be to change state law to allow counties to collect sales tax within city limits, in addition to city taxes, if the county sales tax is approved by voters. While this policy would be new to Nebraska, it is common in many other states, particularly when there is a greater financial relationship between county governments and local public school districts.

This additional revenue could be used to offset the property tax, or eliminate other taxes harmful to economic growth. However, some counties have very few taxable sales within their jurisdiction, such as Banner, Blaine, and Hayes counties. This means that a locally levied sales tax could bring some relief for certain counties but is not a solution for every county.

In 2019, the Nebraska Legislature adopted a limited exception to its restraint of county sales tax when it enacted Legislative Bill 472. The measure, which was adopted over the veto of the governor, allows for Gage County to impose a half-cent countywide sales tax, in addition to the city sales tax levied in municipalities like Beatrice. The tax is only meant to exist for the period of time needed to allow payment of a federal judgment owed by Gage County, which has required the county to maximize its property tax levy.

Due to the urgency of the judgment, the Legislature decided that the Gage County sales tax would not require voter approval, as with other local option sales taxes. Instead, the tax could be levied with the approval of the county board of supervisors.

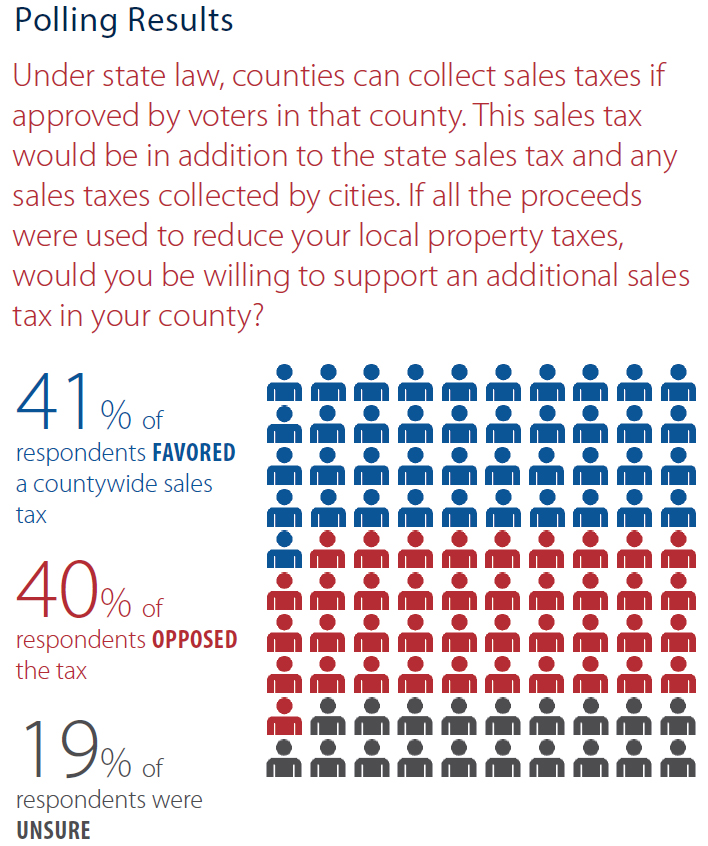

It is unlikely that the approval of LB472 is an indicator of broader support among lawmakers for countywide sales taxes. However, polling of Nebraskans shows the idea could potentially win local voter approval, particularly in some rural areas, if the law allowed such an approach. In total, 41% of voters favored a countywide sales tax, 40% opposed it, and 19% were unsure.

Opposition was strongest in three of the four districts polled in Douglas and Sarpy County, where the plurality of voters rejected the policy. But in districts that included a variety of Central, West, and Northeast Nebraska counties, the largest number of voters supported the idea.

Most taxpayers in Douglas and Sarpy County already pay local option sales tax to their cities, as well as local occupation taxes that increase the cost of many of their daily purchases, which may explain their general reluctance. In other parts of the state, however, municipalities may not currently levy a sales tax at all, or the rate is low enough that an additional county sales tax to reduce property taxes would not be seen as an undue burden.

While a tax does not automatically become a better economic decision just because it is approved locally, it is at least easier to change and review with regularity if it depends on the support of local voters, rather than a state legislature.

Economic Development and Business Incentives

A common question is whether Nebraska could significantly reduce its property tax burden by eliminating business incentives and economic development programs. The answer is about as complicated as the many programs that exist under that umbrella.

“Economic development” is a catch-all term used by many to mean activities that promote migration, jobs, and investment in a specific area, but really, it is most applicable to government policies that direct economic activities for specific businesses or industries. A more appropriate term for the general improvement of business, wages, and other measurements of prosperity that arise from free enterprise and a government providing core services would be “economic growth.”

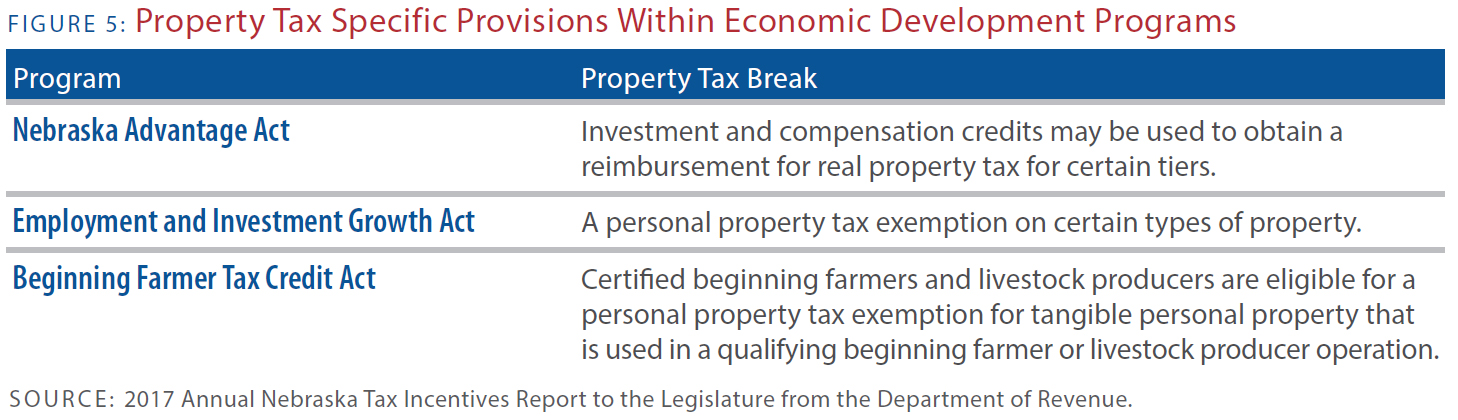

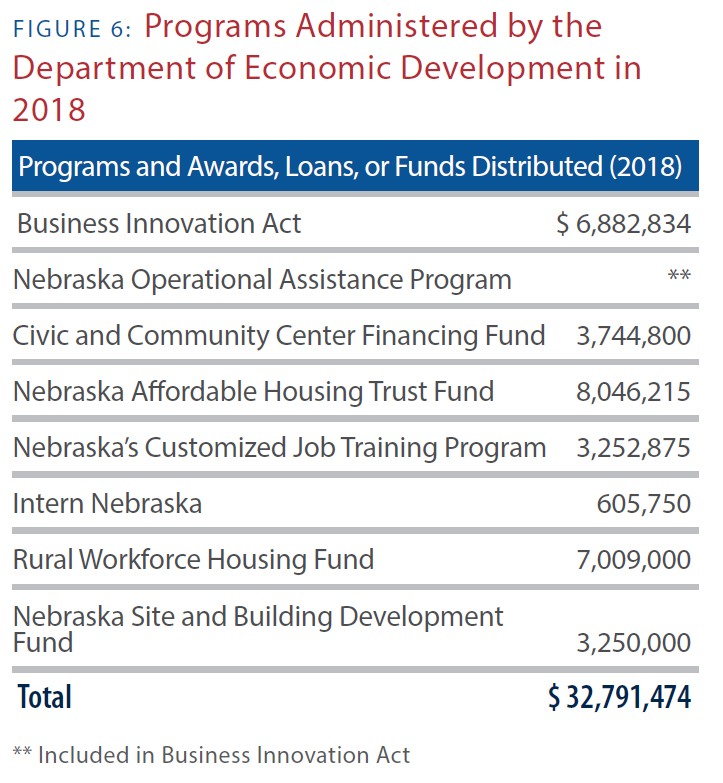

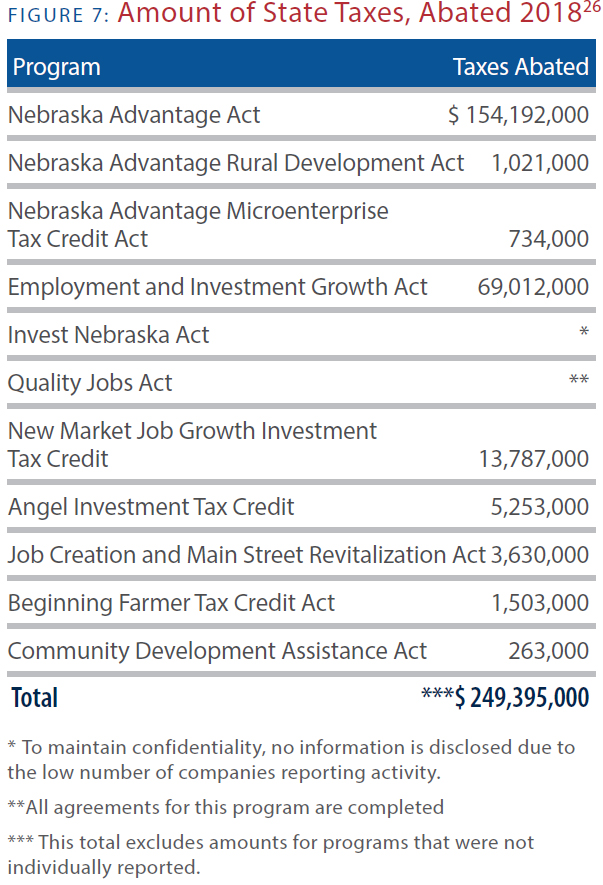

Tax incentives are abatements or tax credits that are designed to provide tax cuts for businesses agreeing to make certain types of investments in Nebraska. These programs do not only offset state taxes like the corporate and personal income tax, or the sales tax, but may also reimburse or abate local personal or real property taxes as detailed in Figure 5.

These incentives are supposed to help the state overcome its many tax policy disadvantages and increase the number and quality of enterprises and jobs that would make Nebraska a more attractive place to live and work. In practice, incentives are pursued for the same reason as sales tax exemptions: in any given legislative session, it is more politically expedient to give a smaller group of market participants a carve-out in the tax code than it is to craft an overarching tax policy with a broad base and low rates.

However, a study24 by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University found that Nebraska could make a significant positive impact on its overall tax burden if it moved away from using tax incentives and instead initiated tax reforms. Mercatus found the revenue lost to incentives was enough to eliminate the state’s corporate tax and still have money left over for additional tax cuts.

But just as with the sales tax, achieving an economically ideal outcome of a better tax system for everyone is much easier said than done mainly because Nebraska has a wide variety of economic development programs, and very different opinions exist in the Legislature regarding these programs.

In addition to state tax dollars being spent by the Department of Economic Development, there are multiple tax incentive programs that are continuously making agreements with businesses for their participation. According to the State of Nebraska’s Certified Annual Financial Report,25

“As of June 30, 2018 the State administered eleven separate tax abatement programs—the Nebraska Advantage Act, the Nebraska Advantage Rural Development Act, the Nebraska Advantage Microenterprise Tax Credit Act, the Employee and Investment Growth Act, the Invest Nebraska Act, the Quality Jobs Act, the New Market Job Growth Investment Tax Credit, the Angel Investment Tax Credit, the Nebraska Job Creation and Main Street Revitalization Act, the Beginning Farmer Tax Credit, and the Community Development Assistance Act.”

Nebraska’s largest incentive program, known as the Nebraska Advantage Act, is scheduled to expire in 2020. There were multiple meetings and hearings on the fate of the state’s incentive program during the interim of 2018. Many rural senators wanted the money to go towards property tax relief instead of a new incentive plan. The 2019 Legislature debated a proposal to replace the Advantage Act, Legislative Bill 720, which was filibustered by many members who prioritized property tax reform over incentives. As a result, the bill failed cloture during the second round of debate.27 As shown in Figure 7, though, there are many other incentive programs in existence, and whatever becomes of the Advantage Act, future tax incentive debates in Lincoln are inevitable.

If corporate incentives are curtailed in the coming legislative session to fund property tax reform, some businesses may experience significant tax increases, while others may see significant reductions. If Nebraska wants to consider reforming its state incentive programs, it should be tied to comprehensive tax reforms that create a more neutral tax policy for all business taxpayers in the state.

Retrace Your Steps

Almost every legislative session, a new economic development program, tax incentive, or tax-carveout is approved by the Legislature. In deciding how to begin reforming these policies with the least disruption, the Legislature should look at the most recent history, identify the newest incentives and carve-outs, and work in reverse order to scale them back or eliminate them.

One suggestion is to look for incentives and programs that are redundant to existing federal or local policies. As one example, the Nebraska Historic Tax Credit (NHTC), which is under the Nebraska Job Creation and Main Street Redevelopment Act, costs the state $15 million annually. The program currently sunsets on December 31, 2022.28 This credit for the restoration of historic buildings, which is also available at the federal level, was only created in 2015, when the state faced a very different budget picture.

In addition, property owners can take part in the Valuation Incentive Program (VIP), which freezes the assessed property valuation for eight years after the rehabilitation, and subsequently property taxes can only increase by 25 percent each year for the next four years for a total of 12 years of property tax relief.29

By removing or capping entry to this relatively new credit, the state will free up millions of dollars per year over time to spend on property tax reforms. In addition, if the Valuation Incentive Program were to be suspended, that would give local governments a broader tax base and possibly lead to lower property taxes in some jurisdictions.

Because virtually all of the potential benefits of a renovation project accrue to those who live, work or sell goods and services in that community, it makes sense for any support for such a project to flow from local sources, whether private or public. This is just one example of many that can be implemented to help reduce the state’s expenditures on incentives and economic development and free up valuable tax dollars for property tax reform.

Property Tax Limitations

No discussion of property tax reform would be complete without discussing what appropriate restraints will be placed on property taxing subdivisions in exchange for any new revenues they receive. Our previous polling shows that Nebraskans have a strong interest in placing greater limits on their climbing local property tax bills. This is important, since history shows that more spending alone doesn’t work to reduce the property tax burden for very long. Taxes kept increasing in 2007 after the creation of the Property Tax Credit Fund, and in 1967, with the elimination of the state property tax.

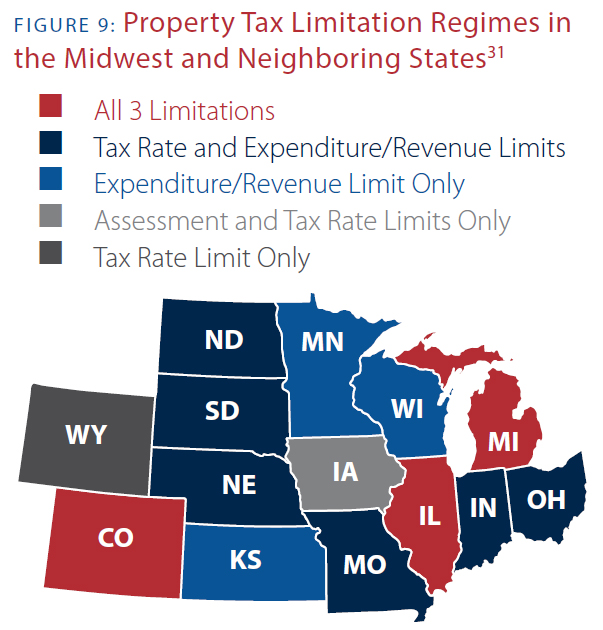

Property taxes will tend to be higher if local taxing jurisdictions have (1) high property tax reliance, (2) low property values, or (3) high local government expenditures.30 In some parts of Nebraska, combinations of all three exist. It is important to note that Nebraska, like 45 other states and the District of Columbia, already has some limitations in place for property taxes. Another barrier in solving the property tax problem is that even with these limitations, property taxes range widely across the United States, and there is no proven combination to keep property taxes low that works for every state. Each state that has implemented limitations serves as a case study where Nebraska can learn from their limitations to see which would best suit Nebraska’s needs.

To truly reform the state’s property tax system, all property taxing subdivisions must come to the table, along with state lawmakers, and be willing to compromise on a solution that exchanges greater property tax limitations with a broadening of Nebraska’s state and local tax bases.

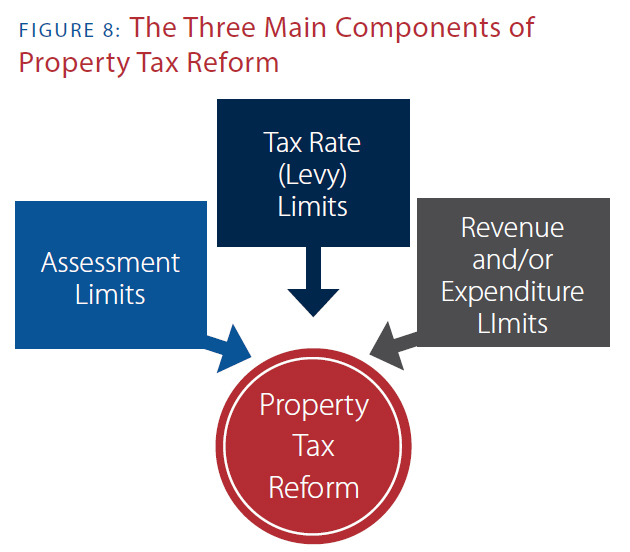

Overall, property tax limitations are broken into three broad categories: assessment limits, tax rate levy limits, and revenue/expenditure limits. Under current law, Nebraska’s property tax system has revenue/expenditure and tax levy rate limitations, and no assessment limitations. A combination of these three limitation types can result in significant property tax reductions for Nebraskans. However, each of these limitations work in very different ways, and any reform must have a clear understanding of how they all work together to achieve the goal of lessening the property tax burden in Nebraska.

Let’s look at each property tax limitation in more detail:

Assessment Limits, Ratios, and Valuations

An assessment limit is a way to avoid inadvertently pricing someone out of their home or land when their assessed value and associated tax burden rises. Nebraska does not currently have an assessment limit statewide. Assessment ratios, as discussed previously, are the percent of property value subject to the tax rate. Residential and commercial properties are taxed on 100 percent of the property’s actual value, while agricultural and horticultural land are taxed at 75 percent of actual value.

One policy option to help curb the growth of property tax liabilities in Nebraska is to set an aggregate assessment cap to keep assessments from growing too fast. Another option is to reduce assessment ratios in Nebraska, as was the case in many years for Nebraska’s history.

Assessment limits are advantageous for a property owner that may appear wealthier on paper due to the appreciation of their property value, yet their income and ability to pay higher taxes may not have risen proportionately. An example of this is would be an elderly homeowner who has paid off their home, yet is on a fixed income, or a farmer who has low income, yet has a very high property tax bill due to the large amount of land on their farm. However, experience from other states suggests an aggregate assessment limitation, which takes the whole state into account, may have fewer unintended consequences that an assessment limit on an individual property.

Otherwise, a restriction on assessment growth for a single property can create large inequities. California decided to limit assessments in 1978,32 freezing the assessments to 1976 values. The law only allowed property tax assessments to increase a maximum of 2 percent per year as long as the property was not sold.33 Once a property was sold, it was reassessed. This means two homes on the same street can have drastically different property taxes based upon the year of purchase. This has created a disincentive for homeowners to relocate and also increases the cost of new construction.

Two of Nebraska’s neighboring states have a form of a statewide aggregate assessment limit. According to Tax Foundation research:

“Colorado caps residential property at no more than 45 percent of statewide assessed value. Iowa, meanwhile, combines a statewide assessment limit with an “ag tie” which implements an assessment rollback if residential property values in aggregate rise faster than agricultural assessments, or vice versa.”34

If an assessment limit were to be enacted in Nebraska, a full review of other states’ assessment limits and the impact on the property market should be evaluated so a detrimental policy like California’s does not result. A well-designed tax limitation will keep taxes in check across the board, not shift the tax burden from one class of property owner to another. Assessment limits alone will not safeguard against tax increases and would need to be part of a bigger reform package including the other two aspects of property tax limitations, if Nebraska lawmakers chose to implement them.35

Changing property assessment ratios also has similar drawbacks. Agricultural property, which is assessed at 75 percent of market value while all other classes of property are assessed at full market value, is a good example. A constitutional amendment was approved by voters in 1990 that distinguishes agricultural land as a separate class of property which must be assessed uniformly and proportionately within that class, but not in comparison with other classes of property.

A reduced assessment ratio on agricultural property may have made property tax increases less costly than they otherwise would have been, but valuation increases have outpaced any difference the ratio change would have made. Further reductions in agricultural assessment ratios offer only a limited use on their own.

In an area where most property is agricultural, there is little other property to tax. That means absent other funds, local taxing subdivisions may only increase property tax rates in response. In areas where residential and commercial property are well represented, such a change would shift property taxes higher on these taxpayers.

However, one exception where certain property should be assessed differently is in the event of a natural disaster. In 2019, Legislative Bill 512 was enacted, which allows temporary property tax relief to owners who are affected by fires, earthquakes, floods, and tornadoes resulting in significant damage to the assessed value of real property.36 This policy immediately benefited many of those that experienced flooding along the Missouri River during the historic March 2019 floods.

There have been recent suggestions and proposals to adjust the agricultural land property tax valuation from market valuation to income potential in an effort to reduce agricultural property taxes. If this were to occur, it would be reversing a law passed in 2006 by the Nebraska Legislature that changed the valuation from income to market.

This leads policymakers to question which is the best approach. According to tax economists, the income potential valuation adds complexity to the tax code, and ultimately does not make much of a difference for agricultural property tax bills.

Switching to income potential is based on the idea that crop prices and yields are volatile, and that paying property taxes is more painful in bad years. But it leads to questions such as how county assessors will consider productivity, soil quality, irrigation, and other factors that speak to income potential. Ultimately, good tax policy should strive for greater simplicity than the income potential method involves.

Tax Rate ‘Levy’ Limit

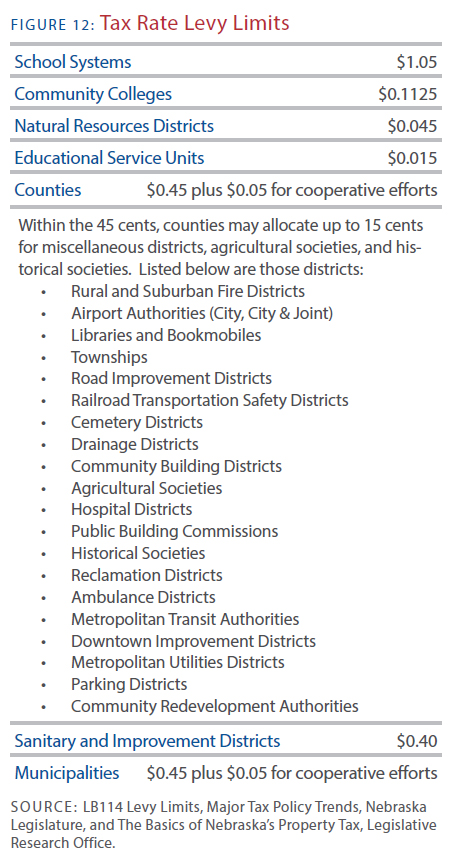

A rate limit, commonly referred to as the levy limit, is the most straightforward limitation, and imposes a cap on property tax rates. Nebraska has overall levy caps intended to provide absolute maximum property tax levies.

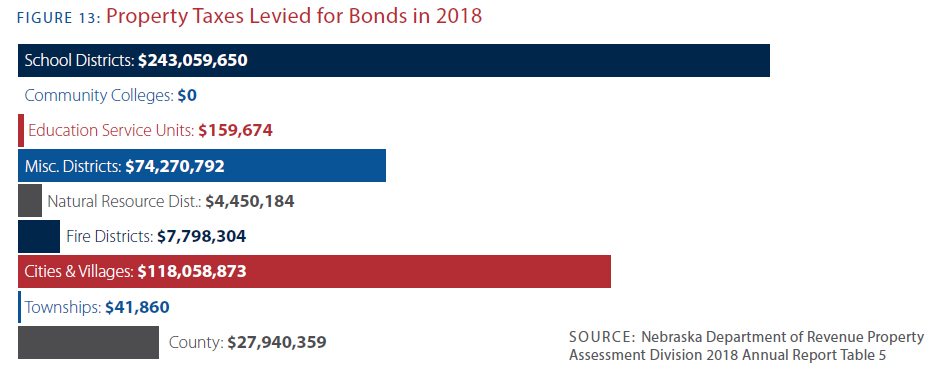

Starting in 1998, property tax levy limits were implemented, limiting local governments to property tax levies of no more than $2.19 per $100 of property value. Caps have varied over time, especially with regard to school districts, as there have been changes in the state school aid formula and funding. Currently, school systems are limited to $1.05 per $100 of property value. Cities, counties, community colleges, natural resource districts, and sanitary improvement districts are also subject to levy limits. The levy limits do not apply to levies for bond issues of any of these local government units, which is why many taxpayers pay more than $2.19.38

Voters may approve an override of the levy limit. If a taxing subdivision, other than a class I school district, wants to levy an additional property tax amount in excess of its cap, they may do so if approved by a majority of the voting electorate, upon a resolution of the governing body voted in favor by 66 percent or more, or by petition signed by 5 percent or more of the voters. Only one resolution and one election for excess levy is allowed per calendar year and if approved is only applicable for a period up to five years.39

In addition to the traditional levy rate limit, Nebraska also has a levy limit that can be adopted in any jurisdiction using the property tax. If a petition is signed by 10 percent of the registered voters of the political subdivision to put a limitation on the budget of the jurisdiction and subsequently approved by a majority of the electorate, then the limitation will take effect for up to two fiscal years.40 This ultimately means that any local government in Nebraska relying on the property tax may be limited by this process.

A recent change to Nebraska’s levy rate limit was enacted in 2019 via LB103.41 This legislation automatically reduces the levies of taxing entities as valuations increase in order to keep the total property taxes collected at the same level. For example, if the valuations in a district were to increase by 20 percent then the corresponding levies would decrease by 20 percent. If the elected board wishes to increase the levy rate, thereby increasing the total taxes collected, then they must hold a public hearing and hold a vote to raise the levy. This is to avoid taxing entities automatically collecting more taxes as valuations rise without a vote.

The most practical way to approach levies in Nebraska would be to tighten or lower levy rate limits for school districts or other taxing subdivisions in concert with a reimbursement of the difference in revenue from state funds.

In the late 1990s, cities and counties had their levy limits reduced. Today, school districts levy the most, and are also typically the subdivisions that levy overrides for school bonds. This is one reason why school districts are the single largest source of the property tax in Nebraska. Schools are also funded through a funding formula established by the state, as well as multiple other revenue sources, such as court fines, vehicle taxes, and alcohol and tobacco license fees.42 If a change occurred in how education was funded at the state level, then an appropriate accompanying policy would be a reduction in the allowed school district levy rate.

However, this approach was tried in 2019 as part of a property tax reform proposal. It was stubbornly opposed by equalized school districts. Some have said that property tax policy and school funding reform must occur separately if a bill is to succeed in overcoming the filibuster. However, it is clear that the path to substantial property tax reform will be tied to school funding in some way.

Revenue or Expenditure Limit

These types of limitations impose a hard constraint on revenue growth and have the same revenue effect as imposing both a rate and an assessment limit combined, without the inequities and distortions associated with assessment limits.43 However, revenue or expenditure limits do not protect taxpayers from substantial tax increases. Government officials still have the ability to adjust levy rates and assessment rates within the overall revenue cap.

Cities, counties, and taxing subdivisions across Nebraska must maintain a base limitation rate on the growth of restricted funds to 2.5%. A governmental unit may exceed the limit for one fiscal year by up to an additional one percent if approved by at least 75 percent of the governing body. A higher percentage may be approved by a majority vote, by the recommendation of the governing body, or by petition signed by at least five percent of voters. Further, a higher percentage may be approved by majority vote at a meeting of residents of the governmental unit after notice is published in a newspaper of general circulation. At least 10 percent of voters in the governmental unit constitute the quorum necessary to exceed the allowable growth percentage.44

A re-evaluation needs to occur as to how these spending and budget caps are working. Again, other states have imposed these with varied success, and a full review of these outcomes should be made. If any other form of property tax limitation is reformed, it is suggested this area also be reformed, as it is an integral tool to ensure local governments are not driving an increase in property tax with excessive spending. One suggestion is also placing a cap on the maximum override any specific district can enact, which will provide some relief from local communities spending in excess of their limit for bonds.45

In the 2019 legislative session, senators heard a proposal by Governor Ricketts to establish a new constitutional cap on the amount of property tax revenue growth local political subdivisions could budget annually. The proposal, LR8CA, would limit the growth of property taxes to 3 percent. The limitation would not apply to other revenue sources subdivisions could collect.

As with other limitations on the growth of assessments, the proposal itself does not reduce property taxes. However, many local political subdivisions oppose the limit because it would prevent them from fully using the property resources in their jurisdiction. One legitimate concern is whether such a limitation differentiates between an increase in property tax revenues due to tax increases, and those which merely result from newly developed or improved property in a community.

Another concern would be if there is a reasonable method for overriding the limitation in the case of an emergency, or if local voters have other ideas about how to use their property tax revenues.

Ultimately, as with other current proposals for a constitutional amendment, voter approval would be required to implement this policy. However, senators have considered advancing this proposal as a legislative bill.

Tax Credits

As should be evident from Figure 1, the Property Tax Credit Fund, which is technically a type of tax credit all property owners receive on their property tax bills, has not significantly changed the course of property taxes over the last decade.

More recently, proposals and initiatives to beef up this approach have revolved around creating a state income tax credit that a property taxpayer could claim each year when they file their state income tax return.

Currently, the property tax credit fund equals slightly less than 7% of the property taxes paid in Nebraska. The latest proposal for a constitutional amendment requiring an income tax credit proposes the state pay 35%—an increase of 400%.

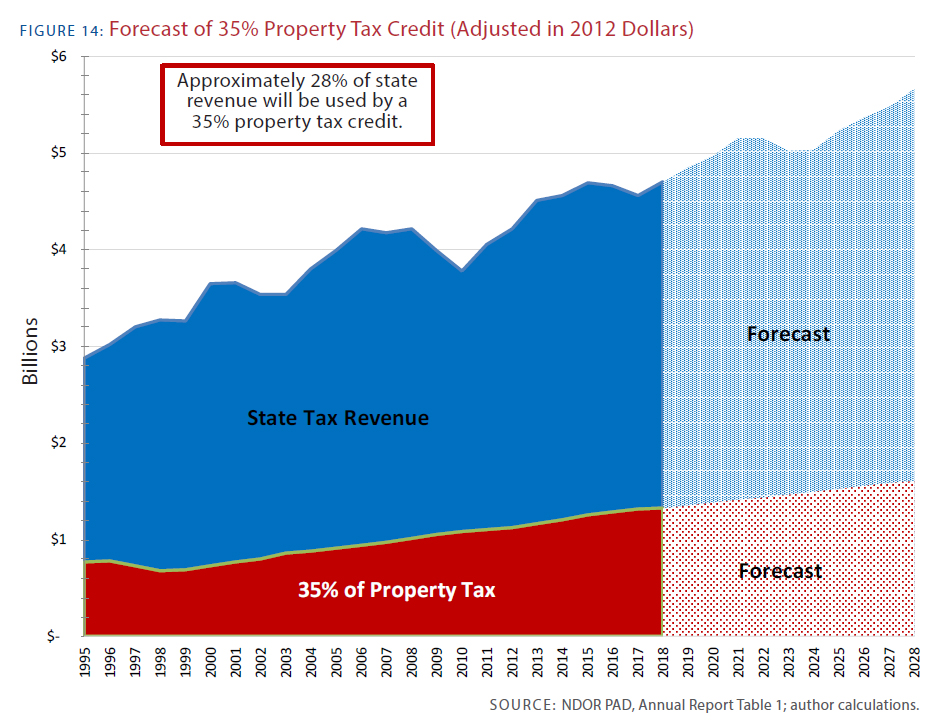

The above figure shows the amount of state tax revenue required to fund a 35% tax credit for property taxes, adjusted for inflation. It also forecasts what such a program could cost in the future. The current property tax credit fund is approved to spend $275 million, whereas if this credit were to be enacted, the amount of state revenue spent on property taxes would jump to more than $1.3 billion, or 28% of total state revenue.

This type of income tax credit would be particularly costly for the state because it would be refundable. This means a taxpayer who does not owe income tax, or owes a sufficiently greater amount of property tax than income tax, could receive a check from the state for the amount of property tax credit they are still owed.

On the surface, there is a certain appeal to this proposal. Effectively, it is a massive income tax cut and tax rebate program for those who own heavily-taxed real property. However, statutory tax rates would not change as a result of the tax credit, for either the income tax or the property tax. Previous Legislatures have debated more modest income tax rate reductions, but like recent property tax reforms, these proposals have been filibustered.

Supporters of the income tax credit approach acknowledge that their strategy is intended to impose budgetary pressure on the state, in hopes that it will motivate the Legislature to reform the property tax system or state spending.

However, it is difficult to say with certainty what would happen if such a policy became law. Even if these efforts to change state statute or the constitution prevail at the ballot box, their implementation will still rely on the Legislature. Undoubtedly, the filibuster would play a factor in how senators would choose to fund this new obligation. But in the end, the state of Nebraska must balance its budget.

This uncertainty seems to have led both supporters of higher taxes and lower taxes to oppose the tax credit idea at times, possibly out of concern that their position would be weakened as a result.

Supporters of higher taxes may believe a much larger share of the state budget would be dedicated to rebating taxpayers, undercutting the ability to use even increased state revenues to fund additional programs. For supporters of lower taxes, their fear may be that the Legislature will be unwilling to say no to any of its current spending decisions and will be forced to impose over $1 billion in state tax increases as local property taxes continue to rise.

A major hurdle for implementation is that a tax credit for property taxes paid will not provide a corresponding property tax limitation on its own. People will pay their property taxes like they always do, and there is no requirement for local governments to change any of their policies.

Another issue with a constitutional amendment for an income tax credit is that it can only be changed by another amendment. The state will still have a responsibility to pay for 35% of property taxes even if it passed new laws to further limit property taxes.

For example, while the cost of the 35% tax credit is a staggering $1.35 billion at current property tax levels, even if property taxes were reduced by 20%, the credit would still cost more than $1 billion annually. That is still many times more than the state’s current spending on the property tax credit fund.

At this moment, many taxpayers may believe a voter initiative may be the only path forward in the face of legislative gridlock. They may be right. However, the tax credit policy could result in significant increases in state taxes, while providing no incentive for local taxing subdivisions to reduce property taxes on their own.

Necessarily, if the property tax ballot initiative should pass, every revenue and spending option—hopefully short of large tax rate increases—will have to be on the table. When the bill rises to $1.5 billion, which is projected to occur in 2024, there will no longer be any room in the budget for a property tax credit fund, sales tax exemptions, or tax incentive programs. Taxing subdivisions that currently have their own local property taxing authority may need to concede their primary means of funding to the state, since state-funded programs would not be subject to a rebate.

For all its flaws mentioned here, the silver lining of a property tax-related credit would be that a new state tax and spending policy would have to be decided upon without delay. But since that scenario will not unfold until at least the 2021 Nebraska Legislature, no one can really know for certain what such a policy might look like.

Property Tax Reform Options in Summary

Assessments

• Study adoption of statewide aggregate cap on assessment growth;

• Avoid individual property assessment caps;

• Reduce assessment ratios in concert with tax rate reductions and state reimbursements.

Economic Development and Business Incentives

• If reformed, replace or reduce incentives with comprehensive tax reforms for all businesses;

• Eliminate incentive programs for which another incentive or tax credit performs the same function (i.e. historic preservation credit), and review incentives and carve-outs that have been recently created.

Education Funding

• Provide a base amount of state aid for students enrolled in public schools;

• Reduce or tighten levy rates or assessment ratios for school districts in concert with additional aid.

Property Tax Rate Limits

• Reduce total allowed levy rate below $2.00, including bonded indebtedness and overrides.

Property Tax Relief Programs

• Consolidate revenues from the Property Tax Credit Fund into overall property tax reforms, such as an increase in TEEOSA, with additional property tax limitations;

Sales Tax

• Broaden the base to include all final consumer goods and services;

• Reduce the sales tax rate;

• Expand the sales taxing authority of local subdivisions, including countywide sales taxes, with voter approval.

Conclusion

Nebraska currently has the 7th highest property tax in the nation and is in need of property tax reform that addresses the underlying problem of a local tax system that imposes too great a burden on the state’s economic growth. However, property taxes have been an issue in Nebraska for over 100 years, and there is no perfect solution to solving the state’s property tax problem. The historical tax changes enacted in 1967 were the result of property taxes, and they are still the number one public policy issue in Nebraska today. Each of the policy proposals offered in this paper have its own set of advantages and disadvantages, and each address a different set of priorities.

What is certain is that more state spending alone will not address the problem. Instead, lawmakers must reform the overall state and local tax structure in order to reduce the financial and compliance costs associated with local property taxes.

Achieving a structural reform is particularly important in the face of statewide economic challenges that have been compounded by the downturn in agriculture. In most recent years, Nebraska has lagged behind the national average in both employment growth and attracting migration from other states. Nebraska’s reputation for high taxes does it no favors in overcoming these challenges. States which gain the most people and jobs at Nebraska’s expense levy significantly lower taxes on average, but do share the commonality of relying more heavily on their sales tax base to fund government services.

During any discussion of tax reform, the Legislature will also need to be aware of the impact a change in tax revenue will have on the state’s budget. Ideally, Nebraska should look to enact revenue-neutral tax reform that results in greater limitations on property taxing authority. Broadening the sales tax base to include as many currently exempt purchases as possible will enable a broadly beneficial reduction in tax rates while maintaining the current level of state revenue.

None of this will be easy, but with courage, compromise, and a willingness to change, property tax reform can make a valuable difference for Nebraskans.

1. LB187 passed in 1979 and took effect in 1981.

2. Nebraska Department of Revenue, Property Assessment Division, 2017 Value & Taxes Levied by Taxing Subdivision & by Property Type, accessed July 26, 2018, http://www.revenue.nebraska.gov/ PAD/research/valuation/annual_taxchg/currentvt_piecharts_state. pdf.

3. Legislative Fiscal Office, Brief History of School Finance Formulas, TEEOSA Tax Force meeting handout, July 13, 2018.

4. Legislative Records Historian, Floor transcripts, LB 1059 (1990), prepared by the Legislative Transcribers’ Office, Nebraska Legislature, 91st Leg., 2nd Sess., 6 March 1990, 10477. http://schoolfinance.ncsa.org/teeosa#anchor67

5. Floor Transcripts, LB 1059 (1990), 6 March 1990, 10513. Senator Scott Moor quote.

6. http://schoolfinance.ncsa.org/teeosa#anchordebate, citations 39, 40, 41, and 42.