Accounting for Property Taxes

Local Governments

Imagine opening your morning newspaper and learning that your city’s property tax rate will jump to one of the highest in the state—and that it still won’t be enough to pay for the services in your community. That is exactly the situation that blindsided taxpayers and elected officials in the city of York, Nebraska.

Nebraska’s property taxes are among the highest in the nation, and local governments’ current accounting practices may be contributing to the problem. Often, local budgets are too convoluted and difficult for the public and policymakers to understand. Due to its hard-to-follow budget, the city of York had spent more money than it had available to operate over many years, unbeknownst to local officials—including the city administrator, mayor, and city council members.

York is now experiencing a financial crisis requiring major tax increases.

Few people object to paying taxes if the taxes are fairly assessed and if the money is being properly used. Unfortunately, too many communities in Nebraska have misused the money they have collected. Spending comes first with governments; if they did not spend money, they would not need to tax their citizens.

Nebraska is home to 93 counties, 503 municipalities, 244 public school districts, and many other political subdivisions such as sanitary improvement districts, community colleges, natural resource districts, and historical societies, among others.1 In total, there are 5,208 political subdivisions in the state of Nebraska.2

Most of these units of local government have the authority to levy taxes, primarily property taxes, to pay for their services. Originally, property taxes were also levied by the state, but for the last 50 years, they have only been levied by local governments in Nebraska. Over that time, the property tax burden for citizens has grown. Today, property taxes collected per capita in Nebraska have reached an all-time high.

There are many legitimate needs facing local governments, but officials need to convince their citizens that they are spending wisely before imposing new taxes, fees, or other costs on residents.

At times, local governments have pursued spending priorities that undermine the trust of taxpayers. Nebraska local governments have spent money on many non-essential projects, such as municipal golf courses, economic incentive packages, swimming pools, athletic stadiums and complexes, and convention centers, at the expense of investments in local libraries, sewer systems, police protection, fire departments, and roads. For local governments that typically face funding constraints, prioritization is the key.

The Problem

In Nebraska, private, for-profit organizations adhere to uniform standards for their financial statements, known as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles or GAAP. Nebraska’s local governments, however, are not subject to these same standards, although a few subdivisions have chosen to use GAAP reporting. This lack of uniformity imposes challenges to a variety of public finance questions, including analysis for bond ratings, assessing a locality’s financial management, and creating useful comparisons of local governments.

Not using uniform reporting standards and procedures creates a transparency problem for the users of local budget information as well. It makes it extremely difficult for residents or elected officials to see where their tax dollars are being spent, or if there is fiscal mismanagement. For Nebraskans to be effective in achieving long-term property tax reform, everyone must have the opportunity to know where the money is being spent through fiscal transparency and accounting uniformity.

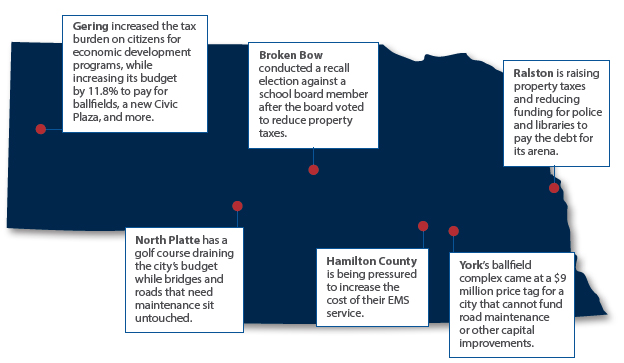

Local tax and spending decisions can have a significant impact on the quality of life and services received in communities across Nebraska. In Ralston, voters approved the construction of an arena which has saddled the city with the challenges of running a failing business operation, and has resulted in higher taxes. Hamilton County is trying to push back against pressure within the city of Aurora to increase the cost of its EMS service. A Broken Bow school board member faced a recall effort after voting to lower his district’s property tax levy. Gering has spent a record amount on economic development programs, while also increasing the city’s budget for non-essential projects. And North Platte has been funding a money pit of a golf course for years, while city infrastructure doesn’t get the attention it needs.

It might be the case that even with better information, locally elected officials and residents would choose all the same outcomes listed here. But with better financial statements, at least Nebraskans could approach these decisions with a more complete understanding of the potential consequences for the policy choices they face. In York, a lack of clear financial information has cost the city its previously competitive property tax climate.

York

York’s property tax rate was once on the lower side for comparable cities. In recent years, the community was gifted a convention center from a generous donor. Taxpayers only had to cover maintenance and operating costs. The city also built a new, state-of-the-art $9 million baseball field complex to help spur economic activity. City employees were also receiving generous compensation, with longevity pay and step benefits, and local infrastructure, including a new well field and sewer plant, was built. But one day in 2018, news broke that the city had significant money problems.

City officials looked back at their financials and realized the city had been experiencing deficits (spending more than they had in available revenue) since 2010. Eight years later, this information came as a shock to those in city government. Each year, the city auditors reviewed the budget and, according to the mayor, never gave any warning that the city was spending itself into financial ruin.

“The city has been using its reserves as a supplement. You can do that only so long. Now we need to reverse that—for the next budget, we are saying the expenses need to match the revenue and major cuts need to happen…”

—York City Administrator Joe Frei

Some may wonder how this could possibly occur. From the perspective of the council members, it certainly appeared that there was more money available in the budget than they were spending. In traditional fund accounting, it looked like actual spending was below budgeted spending. City leaders took this as a sign that there was plenty of money available to spend on new projects, such as the $9 million ballfield complex. What they did not know is that the surplus they saw in their budgets was in fact the city’s reserve, and they were unknowingly spending their reserve funds. After this debacle, the city administrator said he was going to change their financial statements to add a line in the budget for reserve funds.

“I’m still trying to figure out how we used every reserve dollar when everyone was doing a good job at not overspending their budgets…. I thought that what wasn’t spent went back into the reserves. I think we should know, to the penny, where the money went. It doesn’t add up. I’m struggling to get my hands around that.”

—York Councilman Barry Redfern

To remedy the situation, city officials have said more than $1 million must be cut from the budget, and all capital expenditures must be eliminated. That means streets that need to be repaired will sit untouched, salaries will freeze, and no new hires will be permitted. According to news reports from the York News-Times, even if York doubled its property tax levy, it wouldn’t solve their dire money problems.

Accounting Methods

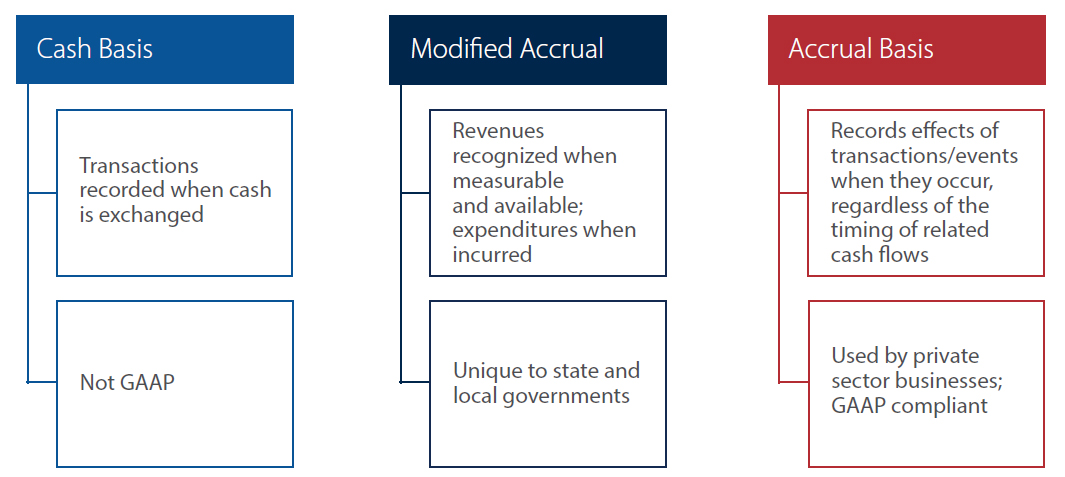

Though accounting is not well understood by many people, the methods commonly used in Nebraska for recording taxes and spending may be a contributing factor to the troubles experienced in York. In Nebraska, there are three main methods of accounting used: accrual basis, cash basis, and modified accrual basis. The main difference between accrual and cash basis is the timing of the transaction. Under an accrual basis, revenue is recorded when it is earned and expenses are recorded when they are consumed. Cash basis, however, records cash when it is received and expenses when the cash is paid.

For example, there are expenses associated with maintaining a city park, such as mowing. There are two different ways to record this expense of tax dollars. Under both methods, the mowing expense will be paid, but the chosen method will determine when the expense will be recorded.

Under the accrual method, the mowing bill will show up on the financial statement as a monthly expense, regardless if it is paid that exact month or not. Under the cash method, the city could misplace its mowing bill and then pay three bills at once. This would not show up on the financial statement until the expense is actually paid. Both methods will ultimately show the same transaction, but the timing is different.

This means if an average taxpayer looked at the city’s financials before it paid its mowing bill, it would look like it had more cash on hand than it really did under the cash basis method. Whereas, if the taxpayer looked at the city’s financials under the accrual method, it would give a more accurate and useful picture of the city’s current financial position.

A disadvantage of the cash method, as illustrated above, is that it might overstate the health of a government that is cash-rich but has large amounts of future payables or liabilities that far exceed the available cash on hand or current revenue stream. The accrual method is a more accurate picture of the government, particularly in the long term. The community of York shows us an example of how accounting can lead to fiscal disaster in local governments and why this is a problem that needs to be addressed across Nebraska.

If the accrual basis of accounting had been used in York, maybe city leaders would have had a better idea of the city’s overall financial position and could have avoided the spending of their reserves.

Another problem with Nebraska’s local government accounting methods is that they are not uniform, sometimes even within the same local government subdivision. For example, the city of York operates on a modified accrual basis. By state law, municipalities of York’s size are required to use accrual basis for their utilities, yet they can use a cash basis for their general operating fund. This combining of accounting methodology is one reason why city council leaders had no idea what was coming.

“So we spent a lot of time going over our expenses [during annual budget formulations and discussions] but we didn’t know what revenue we were using.”

—York Councilman Barry Redfern

The Solution

The State of Nebraska should require that local governments use GAAP accrual basis accounting.

Fiscal transparency is necessary if local property taxes are to be sustainably reduced or kept under control in Nebraska. Even if the Nebraska Legislature were to enact significant property tax reforms, local spending will still remain the primary driver of property taxes in the state. Citizens and elected officials need tools that create fiscal transparency, to see what actions are being taken by their local government, and that allow them to act in the best interest of their community.

It should be noted that a lack of transparency in local government finances does not necessarily mean that officials are intentionally hiding anything or not issuing a yearly budget. It can simply mean the reporting methods are not easy to understand. To counter this problem, the private sector in the United States is required to follow GAAP accounting for clear and easy to understand financials, but the State of Nebraska does not require that of its local governments.

There needs to be a state statute that instructs local governments (primarily counties, cities, and school districts) how to report their annual financials. This is necessary, not only because almost every other state in the country requires it, but because uniformity of methodology and reporting is necessary for full financial transparency. School districts are the largest single consumer of property tax revenues in Nebraska, yet all school districts with the exception of Omaha Public Schools report their finances with cash basis accounting. Omaha Public Schools uses modified accrual, while reporting to the Nebraska Department of Education on a cash basis.3

If Nebraska local governments were required to follow GAAP accounting on an accrual basis, similar to that of the private sector, then it would give citizens and lawmakers a better picture of what was being spent and a more accurate current financial condition. Eventually, it would be ideal if all local governments issued a comprehensive annual financial report (CAFR), which is a financial document that provides a more detailed financial and historical context of the local government.

Other Issues to Consider

Of course, the use of the word “require” or “mandate” will immediately suggest to some that this policy suggestion will increase costs for taxing subdivisions like so many other mandated policies. Many local governments in Nebraska have very low populations and limited resources. The idea of a mandated change to their accounting standards would come at a significant cost.

Many local municipalities in the more rural areas of Nebraska have employees that serve many different functions and to add another task to their daily duties might require the hiring of an additional staff person.

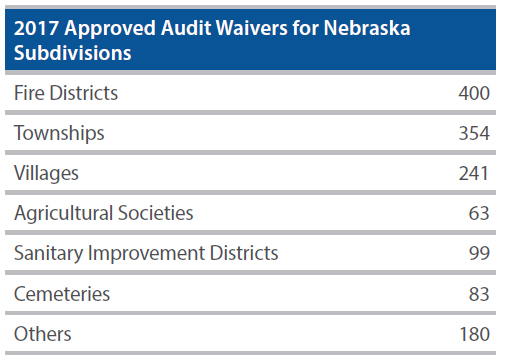

Under current Nebraska state law and Nebraska’s Administrative Code, all local political subdivisions are required to file annual audit reports with the Auditor of Public Accounts. Subdivisions are allowed to request a waiver from the audit requirement according to State Statute 84-304 (4b). There is a review process for the waiver request and the main criterion for a waiver is the dollar amount of total disbursements. The current threshold for allowing an audit waiver is if expenditures for the year exceeded $300,000 or not. In fiscal year 2017, the State Auditor approved 1,420 waivers:4

Similar to the audit waiver law in Nebraska, a comparable threshold should exist for financial reporting. Twelve states have established thresholds where GAAP compliance is not required. These thresholds are generally based on population, revenues, or expenditures. In the case of school districts, it is based on enrollment.5

However, with this exemption there are unintended consequences that might need to be addressed at some point in the future. Some of these subdivisions requesting waivers still need to ensure their financial statements are accurate and transparent for their taxpayers and residents. For example, in 2017, the Village of Abie, Nebraska, was granted a waiver from the State Auditor’s office because their budget and expenditures were below the threshold, yet the independent accountant’s compilation report6 states:

“Management has elected to omit substantially all of the disclosures ordinarily included in financial statements prepared in accordance with the cash basis of accounting. If the omitted disclosures were included in the financial statements, they might influence the user’s conclusions about the Village’s cash receipts and disbursements. Accordingly, the financial statements are not designed for those who are not informed about such matters.”

Citizens should be able to read their financial statements and know where their tax dollars are going, regardless of their community’s size or if a waiver is granted. There should be a change in the report requirement of waiver governments via the State Auditor so residents can understand their financial statements, even if they are not complying with GAAP standards. All users of the financial information should be able to understand what their community is spending money on.

Who Else Does It?

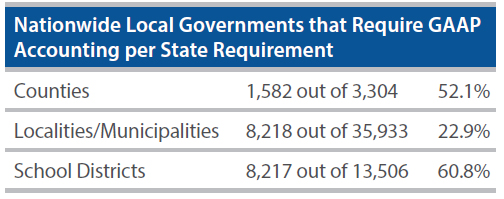

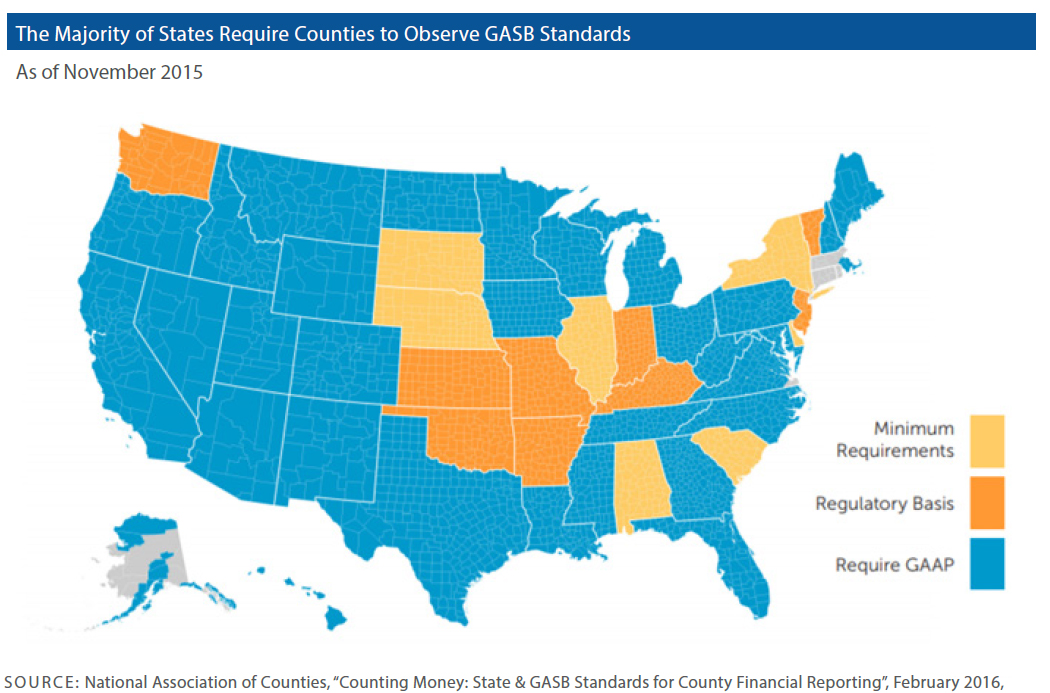

According to a survey report issued by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) in 2008,7 36 states have either laws or regulations that require at least some of their political subdivisions to follow GAAP. School districts are required to follow GAAP in 34 states and 28 states require GAAP for their counties. In 27 states, some other local governments are also required to follow GAAP.

In some states, certain governments are required to conform to GAAP but for some reason choose not do so, and there is no enforcement mechanism available or used by the state. GASB found that if all governments are complying with their state’s requirement to use GAAP, then the maximum impact would be as follows:8

GASB, however, does not look at state GAAP requirements for governments other than counties, localities/municipalities, and school districts.

A study by the National Association of Counties9 in 2015 found that 32 states require counties to follow GAAP. In another 13 states and the District of Columbia, there are 295 more counties that choose to file their financial reports according to GASB standards. As a result, almost three-quarters (71 percent) of counties report their annual financial information following GASB standards in the format of basic financial statements and on an accrual basis of accounting.

Almost a fifth (19 percent) of counties use a financial reporting format decided by their state and other comprehensive basis of accounting different from GASB standards. Nine states (Arkansas, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Missouri, New Jersey, Oklahoma, Vermont, and Washington) ask counties to follow an alternative method of financial reporting and accounting to GAAP. The state determines the framework, including measurement, recognition, presentation, and disclosure requirements of the county financial reports. Another ten percent of county governments use basic financial statements approved by GAAP, but they do not use accrual accounting. Most of these county governments are on the smaller side; 94 percent of them have less than 50,000 residents.

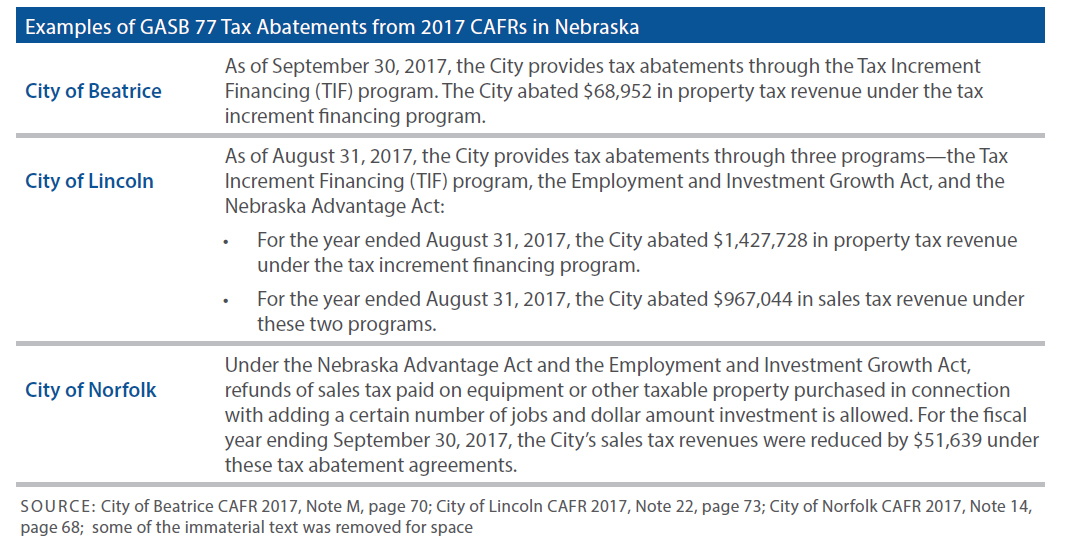

In 2017, there were six Nebraska local governments that received a certificate for Achievement for Excellence in Financial Reporting for going beyond the minimum requirements. Not only did they comply with GAAP reporting, but they also prepared a comprehensive annual financial report (CAFR) for additional transparency and full disclosure of their financials. These local governments in Nebraska that chose to invest in fiscal transparency by publishing a CAFR are: Beatrice, Douglas County, Lincoln, Norfolk, Omaha, Papillion, and South Sioux City.

CAFRs are financial reports that follow the GASB standards and are intended to provide a more robust financial and historical context of the county government. A CAFR’s additional discussions and analyses of county trends and statistical data add to the picture of a county’s financial standing. Bond rating agencies and bondholders use the additional information from a CAFR to assess the investment risk of the county government. Eighty-one percent of large counties—with more than 500,000 people—report using a CAFR. CAFRs are not exclusive to large county governments, but large counties are more likely to issue municipal bonds on a regular basis.

The Opportunity

Understanding

There is great opportunity for Nebraska to require more stringent financial reporting standards of its local governments. As illustrated with York, locally-elected officials have a hard time reading complicated financial statements, which can ultimately lead to overspending and higher taxes. Residents also need to be able to easily read financial statements so they can be more involved with their local governments. Understanding government financial reporting helps users of this data comprehend how their local governments function and deliver services to their residents. It can also help them understand how and why they are taxed in the first place.

Bond Ratings and Cost of Debt

Independent and capital markets recognize GASB as the official source and standard setting organization for state and local governments, which suggests GAAP accounting. If a local government’s financial report uses GAAP standards, it can lower their costs for borrowing, such as the interest charged on bonds, because the financial statements are easier to follow and there is more transparency.

For example, the city of York had over $27 million in outstanding debt as of September 30, 2017, yet the city of York does not have a bond rating.10 If the city were to switch to GAAP accrual basis accounting, it could possibly lower their debt service cost as well as allow the city to receive a bond rating.

Economic Development

Another benefit would be more transparency regarding economic development incentives. GASB has issued Statement 77, a requirement of their standards which charges all state and local governments conforming to GAAP standards to disclose information regarding tax abatements that affect their revenue-raising ability on their financial statement.

GASB Statement 77 applies to all taxes, including exemptions, credits, rebates, or traditional abatements. In a time where many are questioning the impact economic development money has on a community, it is appropriate that this information be available for proper analysis and discussion.

Conclusion

Local government policymakers face many challenges. For these officials to make good decisions, they must first have good information that they can understand. Few people object to paying taxes if the taxes are fairly assessed and if the money is being properly used. Unfortunately, too many communities in Nebraska have misused the money they now have. Clear and understandable financial statements are an essential tool to help set the priorities that can keep taxes low.

Nebraska’s 93 counties, 503 municipalities, 244 public school districts, and many other taxing political subdivisions have the authority to levy property taxes to pay for their services. But Nebraska may be at a breaking point today, as property taxes have reached an all-time high. At the local level, officials can help rein in this tax burden by helping to identify where and how these dollars are being spent. That is nearly impossible to do without financial reporting that is easy to find, easy to read, and easily comparable with subdivisions across the state.

It is time the state of Nebraska enacts a law that mandates that local governments comply with GAAP accounting standards for uniformity and transparency. Providing local elected officials and Nebraskans with better tools for local financial transparency can help our officials earn the trust of their constituents, improve financial management, and enter into major local policy decisions with the best information possible.

Endnotes

1. Total list of subdivisions in Nebraska: Agricultural societies, airport authorities, cemetery districts, cities and villages, cities and villages – utilities, community colleges, community redevelopment authorities, counties, county proprietary funds, ESUs, fire districts, healthcare facilities, historical societies, housing authorities, miscellaneous districts, natural resource districts, public power districts, road improvement districts, sanitary improvement districts, school districts, townships, water districts.

2. Author summed the figures for both the political subdivision budgets received in FY2018 and political subdivision audits/waivers received in FY2018 for the total. http://www.auditors.state.ne.us/

3. Email from Administrator of Financial and Administrative Services with the Nebraska Department of Education dated November 30, 2018.

4. Email from Assistant Deputy State Auditor dated December 6, 2018.

5. GASB, State and Local Government Use of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles for General Purpose External Financial Reporting, March 2008, page 3, https://www.gasb.org/cs/ContentSe rver?c=Document_C&cid=1176156726669&d=&pagename=GASB %2FDocument_C%2FDocumentPage.

6. Independent Accountants Compilation Report for the Village of Abie dated December 15, 2017, found in the Nebraska Auditor of Public Accounts local governments query, http://www.nebraska.gov/auditor/ reports/index.cgi.

7. GASB, State and Local Government Use of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles for General Purpose External Financial Reporting, March 2008, page 3, https://www.gasb.org/cs/ContentSe rver?c=Document_C&cid=1176156726669&d=&pagename=GASB %2FDocument_C%2FDocumentPage.

8. Private email communication with Dean Michael Mead, Senior Research Manager for GASB.

9. Dr. Emilia Istrate, Cecilia Mills, and Daniel Brookmyer, NACo Policy Research Paper Series, Counting Money: State & GASB Standards for County Financial Reporting, February 2016, Issue 4, https://www. naco.org/resources/counting-money-state-and-gasb-standards-county-financial-reporting.

10. Independent Audit Report of the City of York for the year ended September 30, 2017, Nebraska Auditor of Public Accounts, page 13, http://www.auditors.nebraska.gov/Audits_Filed/2017/York_FY2017. pdf.