Nebraska’s Crowded Budget and its Impact on Property Taxes

It’s well known that Nebraska has high property taxes, with government statistics showing that Nebraska’s property tax ranks 7th highest in the nation.1

While it may not seem like it, currently, the State of Nebraska spends a significant amount of money trying to mitigate the problem, arguably with little success. In conjunction with this, Nebraska’s total state spending is at record levels, reaching more than $11.8 billion per year or $6,180 per person.2

Since the property tax is a local tax in Nebraska, the state’s role in changing the tax is limited to mandating changes to local property taxing authority, or using its own revenue from other taxes to attempt to replace local property tax collections. This means if more money is spent on property tax relief, less money may be available to spend on other areas in the state budget.

For example, in last year’s budget, there were spending increases in the TEEOSA state aid formula for public schools, Medicaid eligibility and utilization, employee salary and health insurance costs, and the homestead exemption, along with other property tax relief programs. This required significant reductions in other areas of the budget, as well as a drawing down of the state’s cash reserve fund, to stay in compliance with the state’s balanced budget law. The challenge lawmakers are facing is how to adequately fund the services Nebraskans expect while making lasting improvements to the state’s property tax burden.

State Budget and Revenue Situation

Adding to the challenge is the fact that Nebraska state government has weathered many budget shortfalls in recent years, largely attributed to less-than-expected revenue growth following a major downturn in agricultural commodity prices. In fiscal years 2016 and 2017, the state experienced the third lowest back-to-back revenue growth over the past 36 years, and subsequently experienced the third lowest growth of the last 17 biennial budgets.3

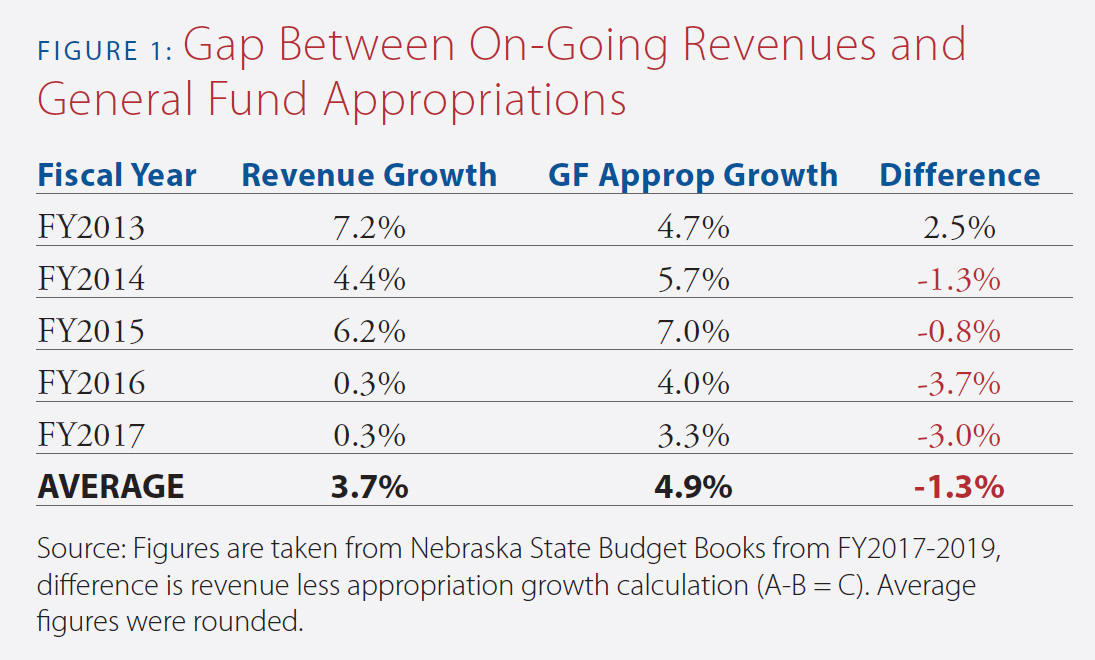

As seen in Figure 1, the average growth rate for the actual revenue collected by the state over the past five years is 3.7 percent per year, which is below the 36-year historical average of 4.7 percent.4

In order to fund additional property tax relief, or any increase in state government, the state must spend its tax revenue. Within the current constraints of state revenue, any new expenditure will ‘crowd out’ spending on other areas of the budget or require cuts to other program funding.

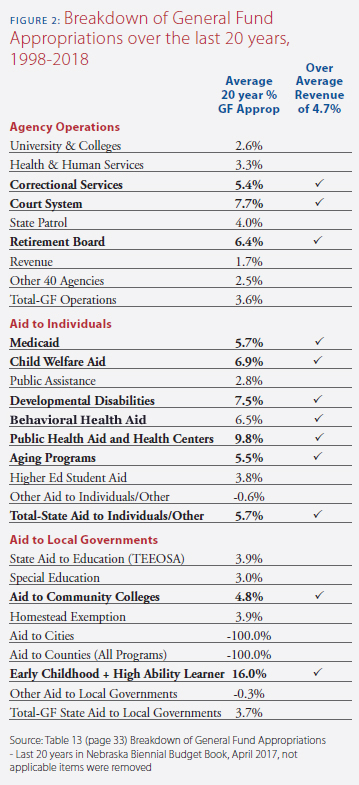

Figure 2 provides a breakdown of average General Fund appropriations for the last 20 years. Because average revenue is 4.7 percent, every area of state government that is growing faster than 4.7 percent is putting pressure on the other areas of the budget to either grow slower or reduce services to make room for the faster growing areas of the state budget.

Since Nebraska law requires the governor to submit, and the Legislature to subsequently adopt a balanced budget, spending cannot exceed revenues.5 Therefore, areas of the budget that are growing faster than revenue, such as Medicaid, corrections, public employee pensions, and aid to individuals are putting pressure on other areas of the budget, including state aid to education, the University and State Colleges, and aid to local governments.

These programs are being ‘crowded out’ of the state budget. In the most dramatic case, aid to cities and counties were entirely crowded out of the state budget when those expenditures were eliminated.

State Spending on Property Tax

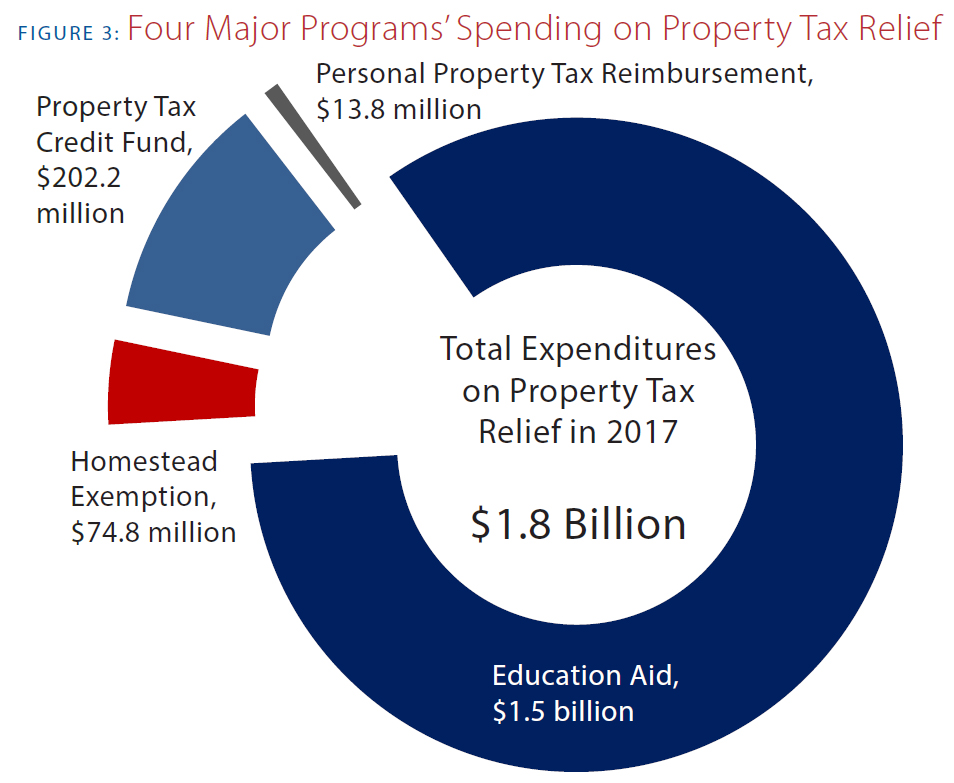

This is not to say local political subdivisions receive no funds from the state for offsetting property tax. Nebraska currently spends a significant amount of state money on property tax measures. Four programs that dominate the state budget discussion are: (1) education aid to school districts, (2) the property tax credit relief fund, (3) the homestead exemption, and (4) the personal property tax reimbursement.6

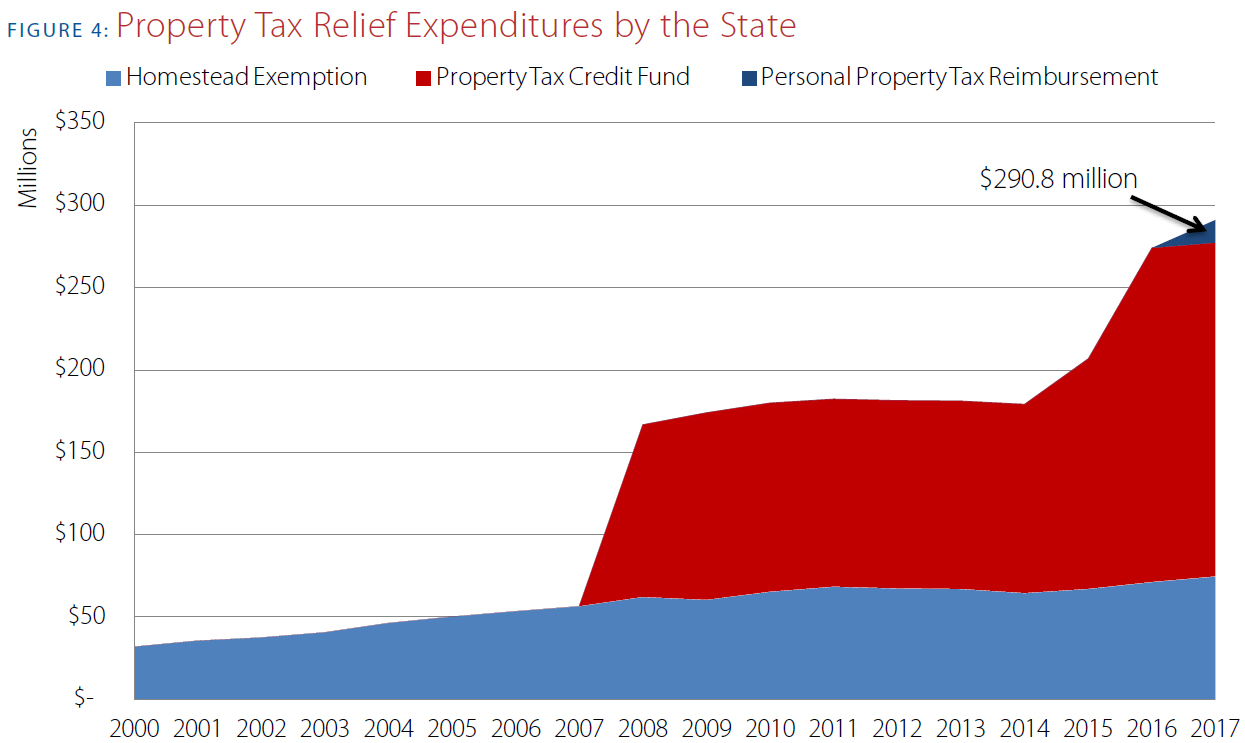

The total state expenditure for these four programs was nearly $1.8 billion in 2017, as seen in Figure 3.7 Some might not consider state aid to education to be a property tax relief measure since its impact on local property tax reliance can be dramatically different from district to district. However, even on their own, the other three programs illustrated in Figure 4 totaled $290.8 million in 2017.8

State Aid to Education

Though today, most school districts receive no equalization aid from the state’s school funding formula, the program lowered property taxes significantly when it was first created. LB1059, or the Tax Equity and Educational Opportunities Support Act (TEEOSA), created a major shift in the funding source for Nebraska’s public schools, with the promise of property tax relief in exchange for an increase in state income and sales tax rates.9

LB1059 decreased the amount of property taxes collected by counties by around $200 million,10 which lowered the local property tax by approximately 20 percent statewide.

Prior to 1990 when LB1059 was enacted, property tax levies ranged from 50 cents to $3.50 per $100 of valuation for school districts.11 This legislation created a property tax levy limitation, lowering the maximum school district levy to $1.10 and creating a spending limitation to ensure districts would not drive up property taxes through excessive spending. Subsequent legislation has lowered the school district levy to the current maximum of $1.05, in absence of a locally approved override of that levy.

While state aid for education has grown at a slower rate than the rest of the state budget, it still remains one of the largest spending items in the state budget, at more than $1.5 billion.

Property Tax Credit Fund

The property tax credit cash fund was created by the Nebraska Legislature in 2007. The fund is a transfer out of the state’s General Fund, thus lessening the amount of General Fund revenues available for other government services. The fund supports a credit property owners can see reflected on their county-issued tax statements. However, property taxing subdivisions, including school districts, are the direct recipients of these funds. The funds provided by the state are meant to replace the local revenue subdivisions forego by providing credits to property owners.

In its inaugural year, the property tax fund was $105 million. This amount stayed constant until it was increased to $140 million in 2014 and then increased again to $204 million in 2015.

In 2016, LB958 made several changes, with the most noticeable being a shift of $20 million of the property tax credits from residential, industrial, commercial and public service sectors to agriculture. This shift was to increase the fund to $224 million. Due to unexpected reductions in new state revenues following this change, the property tax credit cash fund was not funded to the full extent. According to the budget passed by the Nebraska Legislature in Spring of 2018, only $221 million has been allocated to the property tax credit relief fund.12

This illustrates that even if legislation mandates an expenditure, the state’s balanced budget law will supersede an individual spending law, like the property tax credit funding legislation. If more money is directed at the fund, yet the state does not have the available funds to do so, there is a good chance the fund will not receive as much as initially planned due to the crowding of the state budget.

Homestead Exemption

This program functions like the property tax credit, but is designed to give property tax relief to qualifying categories of homeowners, particularly the elderly, some veterans, and disabled Nebraskans. Local governments receive state-funded reimbursements where property taxes are not collected due to the exemption. The homestead exemption has existed since 1969 and the current version we are familiar with today was created in 1979 by LB65.13

Recently the amount for the homestead exemption was set at $78.2 million, yet because 2016 saw an increase in the amount needed to reimburse local governments, future homestead exemption appropriations have been set at $81.3 million for the current and future years.14

Personal Property Tax Reimbursement

In 2015, the Legislature enacted LB259, which created an exemption of the first $10,000 of valuation of tangible personal property in each taxing district. The state reimburses the local government for the funds lost through the exemption, a hold harmless provision.

In its first year, the tax loss to local governments was $13.7 million. Although the expenditure to the local governments is less than originally anticipated by the state, there is still a small increase each year the state must account for.15

Crowding in Nebraska and Property Tax Relief vs. Reform

Every year, there are lobbyists and special interests in Lincoln that court lawmakers to either create a new program or increase spending in a certain area. Meanwhile, our state has experienced multiple budget shortfalls with less-than-anticipated revenue collections. As illustrated in Figure 2, many areas of state government are growing faster than revenue, putting pressure on the other areas of state government.

The various parts of the state budget must work together to be balanced. Many people have discussed increasing spending for property tax relief, expanding Medicaid, spending more on schools, or creating new tax credits or exemptions. All of these things cost money, and will come at a price. Particularly in the current revenue picture, new programs and spending cannot occur unless at least one of two things happen—either cut spending in other areas or raise taxes.

It’s clear the state will have to financially support any plan to lower property taxes, since the revenue-generating ability by local subdivisions is limited or at its maximum allowed by law in many taxing districts. However, the support the state provides does not need to come in the form of spending alone. The state could give local subdivisions more options to fund their needs locally with voter approval, such as expanded local sales tax authority.

The state could also redirect funds currently spent on property tax credits, or state revenues currently lost to exemptions, to substantive property tax reforms that require more meaningful limitations on property taxing authority. Under the current relief programs, Nebraskans are still paying high property taxes. It’s likely that Nebraska’s local subdivisions will always have some level of property taxing authority. But if the state were to take a larger financial responsibility to alleviate the costs of these local political subdivisions, it makes sense that greater limitations on property taxes should come along with those funds.

The ultimate question lawmakers need to ask themselves is, “Will more spending alone fix the property tax problem?” Property tax relief programs, excluding TEEOSA, have increased their spending from $50 million to nearly $300 million in the last decade and property tax bills are still intolerably high for many taxpayers across the state. At the same time, state revenues have been unstable and have proven difficult to forecast accurately, creating budget uncertainty for state-provided services.

Senators in the Nebraska Legislature will eventually have the final say, but spending more money on the property tax without additional limitations to property taxing authority will only add to the state’s already crowded budget and likely lead to significant increases in state taxes. To succeed at providing needed revenues at both levels of government, while improving Nebraska’s overall tax system, Nebraska’s efforts on property tax relief must mature into property tax reform.

Reforming the property tax will not only address the public’s greatest complaint about Nebraska’s tax system, but also provide greater certainty to lawmakers about a part of the state budget that is increasingly crowding out other essential government services.

Policy Considerations

Many advocates correctly note that state aid to property taxing entities, particularly public school districts, has grown at a slower pace than the rest of the state budget. However, the pressure to spend limited revenues that might otherwise go to these property taxing entities on Medicaid, corrections, and pensions, will not go away, nor will the desire to improve Nebraska’s state tax system.

Nebraska’s budget is already crowded with many programs vying for more funding while also experiencing less-than-anticipated revenue collections. These circumstances make it especially difficult for state policymakers to commit to paying more for expenses currently shouldered by property taxes.

The public’s general fatigue with the level of taxation also makes it politically difficult for the Legislature to expand its own taxing authority or to authorize local subdivisions to collect other taxes that may replace property tax revenues. But any solution to meaningfully address property taxes will require a broadening of the state and local tax bases. At the same time, local political subdivisions must come to the table with a willingness to accept additional limitations on property taxing authority. If the Legislature makes a commitment to property tax reform, there also need to be rules in place that create fiscal certainty for the state.

These decisions will be challenging for everyone involved. Any policy that emerges from such a compromise must take the entire state into account, in order to forge a consensus that overcomes a filibuster in the Unicameral.

In an upcoming report, we will discuss policy options that the Legislature can explore to enable lasting property tax reforms for Nebraska.

About the Author

Sarah Curry is the policy director at the Platte Institute. Previously, she was the director of fiscal policy studies at the John Locke Foundation in Raleigh, North Carolina. Sarah began her policy work for the North Carolina State Senate as a research assistant for the chairs of the Senate Agricultural Committee and headed the research efforts for the Regulatory Reform Committee. Sarah earned her bachelors of science in business administration with a minor in government from Nicholls State University in Thibodaux, Louisiana, which she attended on an athletics scholarship. She then earned her international masters of business administration with a plus certificate in finance from Gardner-Webb University in Boiling Springs, North Carolina.

Endnotes

1. Walczak, J. (2017, January 16). How High Are Property Taxes in Your State? Retrieved August 7, 2018, from https://taxfoundation.org/how-high-are-property-taxes-your-state/

2. Curry, S. (2018, July 24). Trends in Nebraska State Spending. Retrieved August 7, 2018, from https://www.platteinstitute.org/research/detail/trends-in-nebraska-state-spending

3. State of Nebraska, Appropriations Committee. (2017). State of Nebraska FY2017-18 / FY2018-19 Biennial Budget (pp. 1-2). Lincoln, NE: 105th Nebraska Legislature.

4. State of Nebraska, Appropriations Committee. (2018). State of Nebraska FY2017-18 / FY2018-19 Biennial Budget As Revised in the 2018 Legislative Session (pp. 25-39). Lincoln, NE: 105th Nebraska Legislature. Table 11 Historical General Fund Revenues and Table 18 Historical General Fund Appropriations.

5. National Association of State Budget Officers, “Budget Processes in the States, Spring 2015”, Table 9, accessed August 6, 2018.

6. Nebraska Administrative Services, State Accounting Division. (n.d.). State of Nebraska Annual Budgetary Report. Lincoln, NE: Department of Administrative Services. Schedule of Major Aid Payments and program costs for Property Tax Credit, Education Aid and Aid to Local Government for Homestead Exemption; Schedule of Budgeted and Actual Expenditures Paid by program for Personal Property Tax Exempt (Budgeted figure).

7. Sum of Homestead Exemption ($71,818,923), Property Tax Credit Fund ($202,153,728) and the Personal Property Tax Reimbursement ($13,800,000), and Education Aid ($1,505,964,100) from Nebraska Annual Budgetary Reports which totals to $1,796,736,751. Rounding was used to come to the $1.8 billion figure.

8. Sum of Homestead Exemption ($71,818,923), Property Tax Credit Fund ($202,153,728) and the Personal Property Tax Reimbursement ($13,800,000) from Nebraska Annual Budgetary Reports.

9. Nebraska Council of School Administrators. (n.d.). 1990: Review. Retrieved August 6, 2018, from http://schoolfinance.ncsa.org/1990-review. Part of a series on TEEOSA policy history.

10. LB1059 fiscal note based on amendments adopted through 3/21/1990.

11. Hearing transcripts, LB 1059 (1990), 32 January 1990, 14. Larry Vontz, Deputy Commissioner of Education for the Nebraska Department of Education, noted that in 1990 school district property tax levies ranged from 50¢ to $3.50 per $100 of assessed valuation.

12. State of Nebraska, Appropriations Committee. (2017). State of Nebraska FY2017-18 / FY2018-19 Biennial Budget (pp. 26). Lincoln, NE: 105th Nebraska Legislature.

13. State of Nebraska, Appropriations Committee. (2017). State of Nebraska FY2017-18 / FY2018-19 Biennial Budget (pp. 51). Lincoln, NE: 105th Nebraska Legislature.

14. State of Nebraska Biennial Budget FY2017-19, Homestead Exemption (Revenue) on page 43.

15. State of Nebraska, Appropriations Committee. (2018). State of Nebraska FY2017-18 / FY2018-19 Biennial Budget As Revised in the 2018 Legislative Session (pp. 43). Lincoln, NE: 105th Nebraska Legislature. “Based on the 2017 certifications from the counties for the locally assessed personal property tax loss and the Department’s most recent estimate for the centrally assessed personal property, tax loss for the current fiscal year equals $13,807,419 below the original estimated and budgeted levels of $15.2 million. This allowed for a reduction in the FY2017-18 appropriation level of $1.3 million allowing for a small contingency for potential amendments. In addition, it is estimated that the appropriation for FY2018-19 can also be decreased from $16.2 million to $14.2 million, a decrease of $2.0 million based on the FY18 actual results.”