Legislative Testimony: LR415, Interim study to examine the state inheritance tax

Chairwoman Linehan and members of the Revenue Committee, my name is Sarah Curry, and I am the Policy Director for the Platte Institute.

Since there has been broad agreement in this committee that Nebraska needs tax modernization, I want to start today with a bit of legislative history. Nebraska’s inheritance tax law was adopted in 1901, based on a law from Illinois. This is noteworthy because Illinois’ inheritance law was the first to introduce a progressive rate structure, and as a result, was challenged in court and eventually heard by the U.S. Supreme Court.[1]

However, an important difference between Nebraska and almost every other state was that its inheritance tax did not allow a high exemption for immediate relatives. When the law was written, direct heirs had to pay 1% on everything above $10,000 received. Today, the law remains mostly the same except the threshold for direct heirs has been increased to $40,000, which is a negligible increase given the time that has elapsed. For context, $10,000 in 1901 would be $306,211 today after adjusting for CPI inflation, which was almost 3,000% since then. This means the exemption for direct heirs should be $306,211, if Nebraska had indexed the inheritance tax brackets to the consumer price index (i.e. inflation).

Another noticeable difference in the Nebraska law from all other states was that the proceeds went into a special fund in each county for the permanent improvement of roads. Most other states levied it as a form of state revenue since this tax predates almost all state income and sales taxes. Today, the proceeds still go into a special fund, however, they are used for more than just road improvement.

Knowing this history is important because one criticism of the law is its current structure.

Many confuse the structure of the inheritance tax with the estate tax. Estate taxes are paid by the decedent’s estate before assets are distributed to heirs and are thus imposed on the overall value of the estate. Inheritance taxes are remitted by the recipient of a bequest and are thus based on the amount distributed to each beneficiary.

Because the taxes are remitted by the recipient, the determination of the inheritance tax is a court process in Nebraska. That means that to determine the tax, heirs will generally need to hire a lawyer to assist. According to a retired estate attorney I consulted with, many lawyers in Nebraska charge one or two percent of the value of the property and it is not unusual for attorneys to be paid more than the amount of inheritance tax.

One solution would be to turn determination over to either the Department of Revenue or the local county treasurer, where forms could be filed by the taxpayers or their accountants. Removing the judicial system would eliminate excessive legal costs by way of simplification and increased competition for tax compliance work.

The historical and current basis for the inheritance tax is owning real estate. Unless the deceased owned real estate, they can completely bypass the tax rather easily because Nebraska has virtually no policing or enforcement mechanism. Current law provides that potential inheritance taxes constitute a lien against any real estate sold, which means if the decedent owns property, everything they own gets taxed to clear the title to the real estate.

Therefore, those most impacted by the inheritance tax in Nebraska are farmers, ranchers, and family businesses, as the inheritance tax makes it difficult to pass property from one generation to the next. The inheritance tax liability means small or medium-sized farmers must sell land, equipment, and in some cases, the entire operation to pay these taxes. Small family business owners face the same challenge as family farmers. Their income is heavy on assets – many of which are industry specific – but not available cash. The result is that parts and sometimes all the business must be sold to pay inheritance taxes.

This is why the Tax Foundation includes the inheritance tax as one of the reasons we are ranked among the ten worst states for property taxes, because it is essentially another tax on real estate.

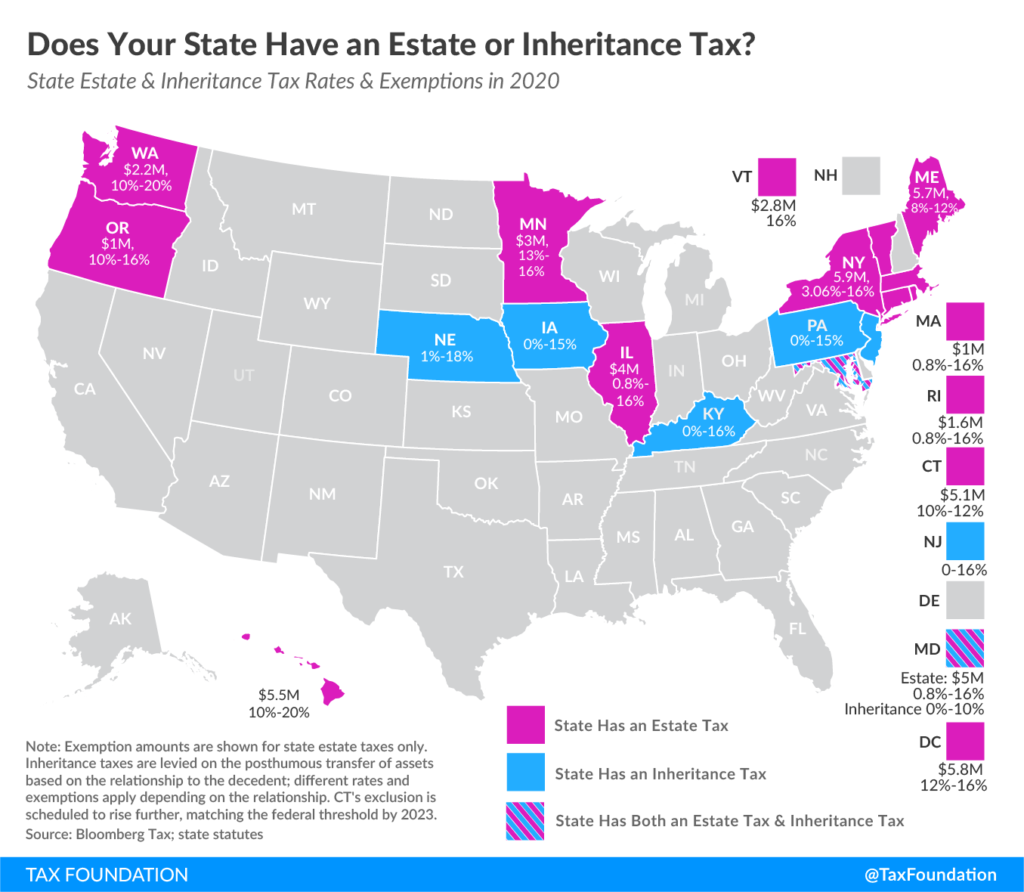

By 1907, 36 states had an inheritance tax, but today, there are only 6 states that continue to have this tax relic still levied on their citizens. This number will likely drop to 5, since lawmakers in Iowa have filed bills and show significant interest in either abolishing or phasing out the inheritance tax. Iowa already exempts immediate relatives like children, grandchildren, parents, and grandparents from inheritance tax.

The Tax Foundation has found that inheritance taxes are among the most hostile to economic growth and as I have already discussed, they have high compliance costs. A study by George Mason University found that states would gain more revenue in the long run by eliminating the inheritance tax due to its economically destructive impact on capital formation and investment.

All that said, I understand the perspective of the counties who use this money for important local government functions. One option that was suggested to the Platte Institute by a county supervisor is that they would support losing the inheritance tax if the counties were given the option to ask voters for a countywide sales tax.

I think that is a good compromise and something the Platte Institute would be willing to work with Revenue Committee members to draft if they felt it would be a worthwhile replacement for the inheritance tax, while keeping county budgets whole.

Another would be to take note of Tennessee and Indiana laws in 2012 which phased out the inheritance tax by gradually raising the exemption amount until the tax was eliminated. One benefit of this tactic is that it would allow the counties time to find an alternative revenue source or eliminate items from their budget due to the decrease in revenue.

I have also included for you some scenarios of how the inheritance tax works regarding decedents living in and out of Nebraska, as well as the most recent Tax Foundation map that shows the remaining 6 states with an inheritance tax, which shows that Nebraska’s top inheritance tax rate is the highest in the nation. Thank you.

Scenario 1:

- Decedent lives in Nebraska and all real and intellectual property is also owned in Nebraska. All inheriting children are residents of Nebraska.

- All real property and assets of any kind would be taxed to the children after allowable exemptions at the applicable rate.

Scenario 2:

- Decedent lives in and is a resident of Nebraska. They own some land in Nebraska and some land in Colorado. All inheriting children are residents of Colorado.

- Only the Nebraska land would be taxed to the children. The children would also pay tax on any other assets owned by decedent (cash, investments etc.) The Colorado land would not be taxable.

Scenario 3:

- Decedent lives in and is a resident of Kansas and owns real property in Kansas and in Nebraska. One inheriting child lives in Nebraska and one lives in Kansas.

- Both children would pay Nebraska inheritance tax on the Nebraska land. Kansas does not have an inheritance tax, and there would be no tax whatever on the Kansas land for either child.

Scenario 4:

- Decedent lives and owns land in South Dakota. All inheriting children live in Nebraska.

- There would be no Nebraska inheritance tax.

[1] Magoun v. Illinois Trust & Savings Bank, 170 U.S. 283 (1898)