Death and Taxes: Nebraska’s Inheritance Tax

Executive Summary

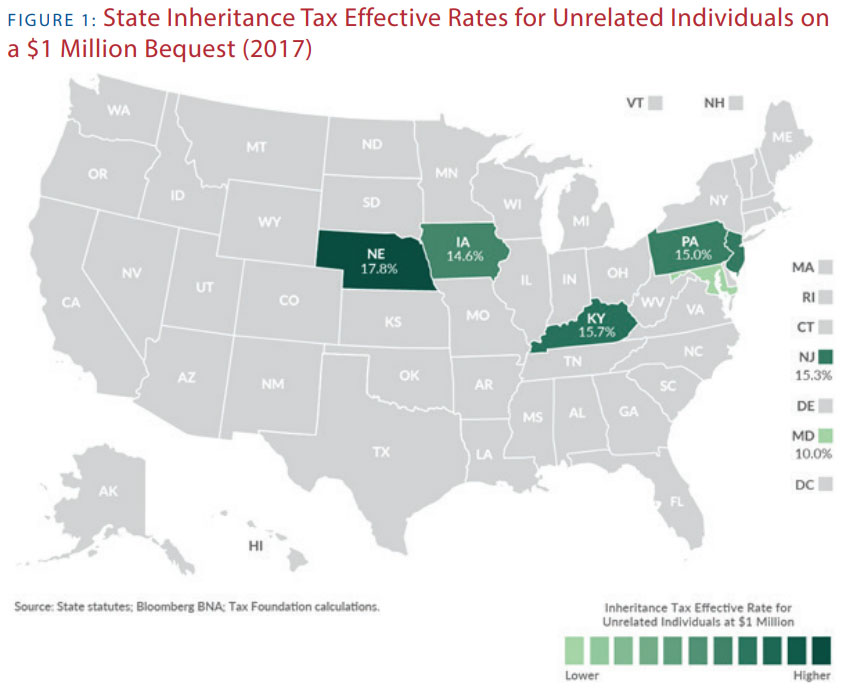

Nebraska has been seeking ways to modernize its tax code for several years, and unfortunately, the inheritance tax has often been left out of the analysis. The inheritance tax is a worthy subject for tax modernization and reform because only six states continue to have this tax: Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Appearing on this small roster has earned Nebraska a regular mention on Forbes’ list1 of “where not to die.”

Almost every state in the nation once levied an inheritance tax at some point in their history. Nebraska’s inheritance tax was adopted in 1901, before the state had a sales or income tax, and has remained relatively the same for the last 120 years. The unique feature about Nebraska’s inheritance tax is that it was and still is the only state in the nation to use this tax as a local revenue source. The inheritance tax, which is levied on the beneficiary of an estate and not on the estate itself, has been shown to have an particularly negative impact on family farms and businesses in Nebraska. Economic studies have found the tax to be hostile to economic growth because of the destructive impact on capital formation and investment, as well as having high compliance costs.2 Importantly, while most states do not make the transfer of property after death a taxable event for property of any value, Nebraska can impose inheritance taxes and compliance costs even on taxpayers receiving relatively modest inheritances.

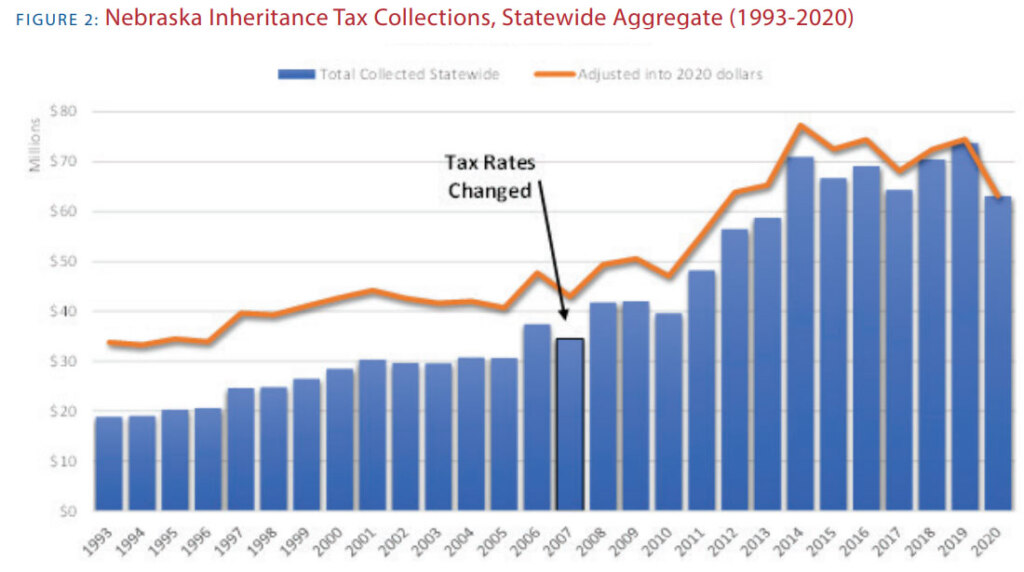

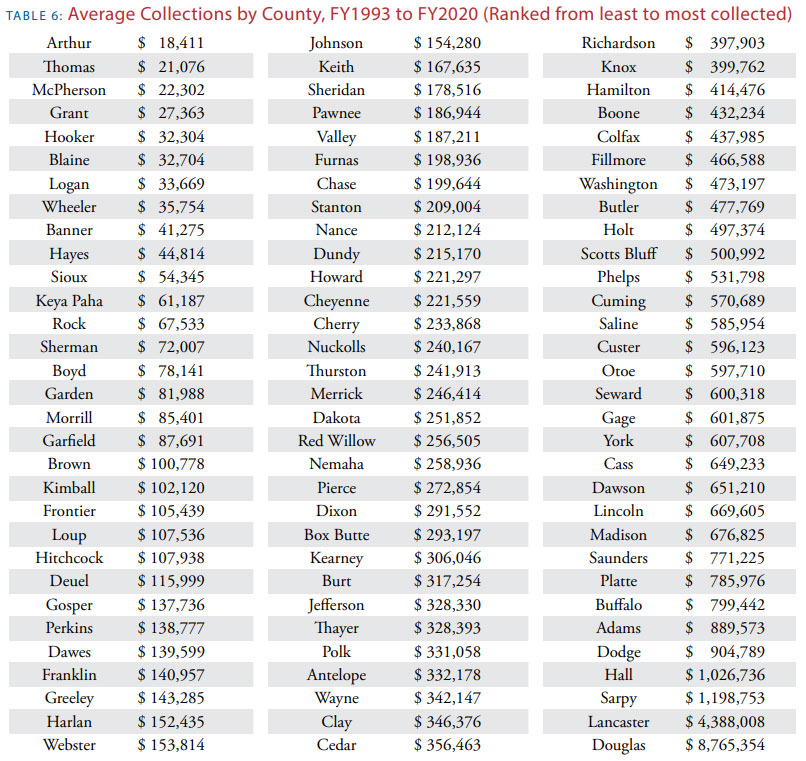

On a statewide basis, inheritance tax collections in Nebraska have ranged from a $18.9 to $73.3 million since 1993 ($33.7 to $74.5 million if adjusted for inflation into 2020 dollars). From a county perspective, Douglas County, the state’s most populated, had the highest amount ever collected from the tax at $16.2 million in fiscal year 2018. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the state’s least populated, Arthur County, holds the record for the least collected in a single year, with fiscal year 2019 producing $0, and the year before only generating $74.

This policy study’s objective is to give a historical perspective of Nebraska’s inheritance tax as well as a discussion of the economic implications of the tax. In addition, this report will include descriptive statistics on the collections of Nebraska’s inheritance tax over a period of years at both the statewide and county level.

The latter section of the study will include a list of recommended policy changes. While the ideal reform option is the eventual repeal the inheritance tax, the problem of cutting revenue to the counties without a property tax increase poses many public policy considerations that must be addressed. Forward-thinking lawmakers have introduced bills for over 40 years trying to repeal the inheritance tax, but none have been successful. Because of this situation, the reform options in this paper are aimed to make the tax less burdensome and to modernize Nebraska’s tax code.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Nebraska State Auditor’s office, the Nebraska Association of Counties, multiple county treasurers, the Nebraska Legislature’s Revenue Committee, and multiple state senators, both past and present. Without the guidance, suggestions, and data provided from these many sources, this paper and its analysis would not be possible.

The author would also like to thank Platte Institute interns Albert Gustafson and Jaliya Nagahawatte for their hard work and contributions.

Introduction

The term “death tax” has been used to describe a variety of different taxes related to the transition of property at the time of someone’s death. However, this term can be misleading, since it can encompass a wide variety of taxes and fees assessed at the time of death. In addition, a tax imposed on the property of the deceased can be called by many different names. The inheritance tax is also sometimes called a succession or legacy tax and is commonly confused with the estate tax.

At some point in their lifetime, almost every Nebraskan will become subject to the inheritance tax, unless they and their family decide to sell their real property in Nebraska and move to another state before their death. Unlike the federal estate tax, which exempts most taxpayers, Nebraska’s inheritance tax can have an impact on anyone who owns or inherits property. However, whether the inheritance tax is paid, avoided, or unpaid due to a lack of knowledge about the tax can vary based on the individual circumstances of taxpayers.

The Difference Between the Estate Tax and the Inheritance Tax

While estate and inheritance taxes are the most frequently grouped together, they function very differently in practice and under the law. An estate tax is imposed upon the privilege of transmitting property, while an inheritance tax is imposed on the privilege of receiving property.3

The biggest difference is that estate taxes are measured and levied on the net value of a decedent’s estate, thus the estate pays the tax before any distribution to heirs. Inheritance taxes are determined by the beneficiary’s share of the estate and the tax is paid for by the beneficiary. One other noticeable difference is that estate taxes are typically graduated according to the size of the net estate, where inheritance taxes are graduated by both the beneficiary’s share and according to their relationship to the decedent.

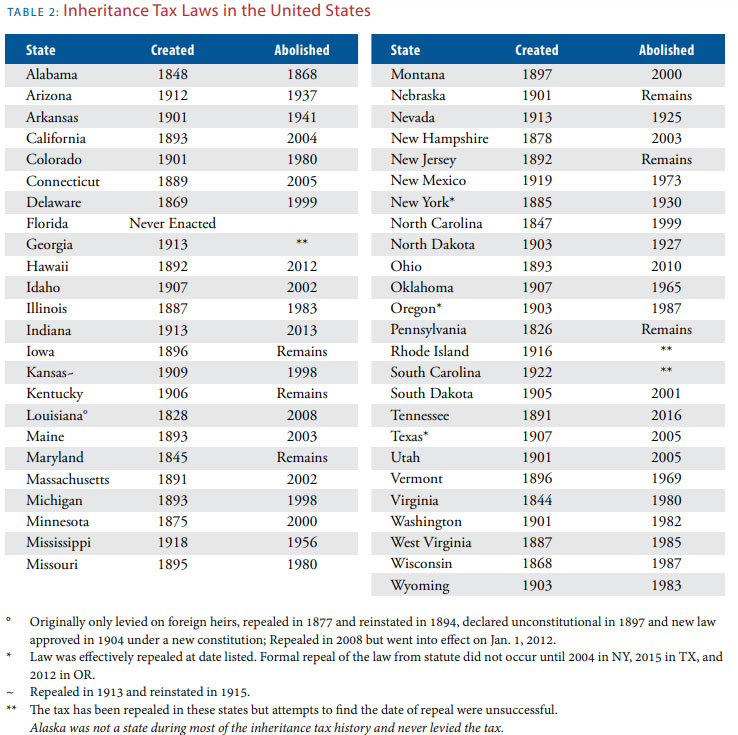

Many states have chosen to repeal their inheritance taxes, especially after the 2001 federal tax changes phased out the federal estate tax credit for state death taxes.4 This was one reason for Nebraska repealing its estate tax in 2007.5

Current National Landscape of the Inheritance Tax

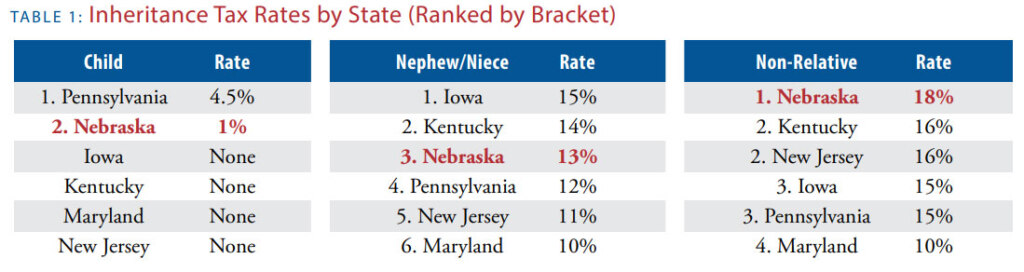

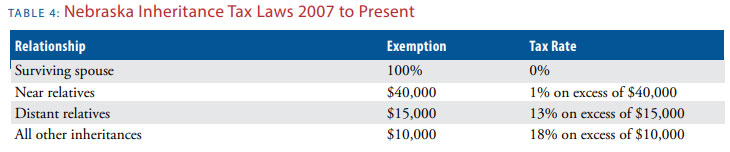

Of the six states that currently impose inheritance taxes, only two states, Nebraska and Pennsylvania, have chosen to tax lineal heirs (children and grandchildren), while the others exempt these relatives. Nebraska currently has the nation’s top inheritance tax rate, 18%, on remote relatives and non-related heirs.6

Inheritance Tax History

The United States has a long history of using the inheritance tax to fund government operations. Primarily, the inheritance tax was used to fund wartime efforts and was levied nationwide from 1797-1802, 1862-1870, and 1898-1902.7

There were efforts to create a nationwide inheritance tax to permanently fund government operations by progressives during the early 20th century. Notably, President Theodore Roosevelt advocated for both an inheritance and income tax, while Nebraska’s George Norris advocated for a 75% inheritance tax as an alternative to a federal income tax.8

In the end, Congress enacted a federal income tax in 1913, followed by an estate tax in 1916, which effectively ended any further discussion of a national inheritance tax. While the federal history on inheritance taxes is somewhat brief, the state inheritance tax history is more extensive and continues into modern times.

Pennsylvania was the first state to levy an inheritance tax in 1826 and served as a model for much of the subsequent legislation on this topic. While a few states enacted the tax during the mid-19th century, many states did not embark on levying an inheritance tax until the 1890s. The progressive movement experienced at the federal level was also a very strong influence in the states. As a result, Illinois adopted the nation’s first progressive inheritance tax on collateral heirs in 1895, creating higher tax rates for heirs, dependent on their relationship.9

The validity of the progressive structure being based on the relationship to the decedent was immediately questioned before the United States Supreme Court in 1898. The court upheld the Illinois inheritance tax law, declaring that the discrimination based upon the relationship to the decedent was considered a reasonable classification, and that the progressive rates were not in violation of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.10 Another important takeaway from this case is that inheritance taxes are not legally defined as a property tax by the court, but a succession tax. Modern economists may disagree with this classification, but the court found that the tax is on the privilege to inherit wealth, and as a result, the states have authority to impose conditions upon the transaction.

The decision by the U.S. Supreme Court was a catalyst for states to immediately amend their inheritance tax laws into progressive structures, and many states that had not yet levied the tax added it to their tax rolls. Until this time, almost every state that levied an inheritance tax had been subject to a considerable amount of lawsuits and constitutional challenges in their respective state supreme courts, forcing states to rewrite their tax laws multiple times.11

A 1941 Iowa Law Review article12 summarized the post-decision environment,

By 1916, 42 states, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico had enacted death duties of one sort or another. The taxes in use at that time ranged from the old-fashioned flat rate on collaterals to the combination inheritance and estate tax…. but the majority of the states were now using the progressive inheritance tax on both direct and collateral heirs, a form which was rapidly becoming the typical American death duty.”

In 1924, state inheritance taxes accounted for 8.2% of total state tax revenue13 and by 1925, only four jurisdictions remained without an inheritance tax: District of Columbia, Florida, Alabama, and Nevada.14 This also marks the climax of controversy between the states and the federal government, as estates were facing multiple layers of taxation.

The compromise solution15 was the adoption of a credit for state death taxes against the federal estate tax, up to a total of 25% of the federal estate tax liability.16 The credit was partly intended to reduce states from competing for affluent residents with the lure of no state inheritance or estate tax.17 The result was that many states enacted “pick-up” taxes equal to the amount of the credit to take full advantage.18 Essentially, the states saw it as free money because the federal tax credit did not increase their citizens’ tax liability. By 1940, there were 33 states using a combination of the estate and inheritance taxes.19 All states at the time, except Nevada, had some form of a death duty (estate or inheritance).

During the mid- and late 20th century, many states decided to forego the inheritance tax completely, replacing it with an estate tax. Other states decided to have a combination estate and inheritance tax, structuring the taxes to capture all the revenue up to the threshold of the federal credit or “pick-up tax.”

States were eventually faced with an ultimatum when Congress repealed the credit for state death taxes in 2001. The phase out of the federal revenue sharing lasted until 2004, which gave states time to decide what to do. After the complete implementation of repeal, the full burden of the taxes would fall on their citizens. As a result, most of the remaining states eliminated their inheritance taxes, along with their estate taxes, to conform with the federal tax change.20 While Nebraska did eliminate its estate tax, which was levied by the state, the inheritance tax, which is collected by county governments, remains in place.

Nebraska’s Inheritance Tax History

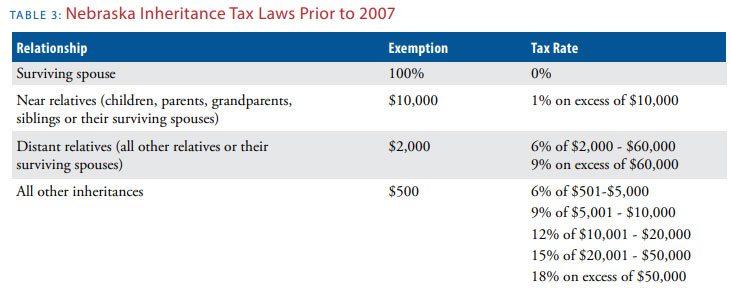

When Nebraska first enacted its inheritance tax law in 1901, lawmakers used the Illinois progressive tax as a model in most respects. However, Nebraska’s original inheritance tax did not include a substantial exemption for inheritances from immediate relatives. A unique feature of Nebraska’s tax was the state’s instruction for county treasurers to keep all the money collected through the tax in a separate and special fund to be spent only on the “permanent improvement of the county roads.”21 Nebraska was and continues to be the only state to use this tax as a local government revenue source.

When originally enacted22, the inheritance tax was $1 for every $100 of the market value of the property received by any immediate family member, with an exemption for the first $10,000 received by each person. The next class of family included any uncle, aunt, niece, or nephew, and the tax rate was $2 for every $100 of the market value of the property received, with an exemption of only $2,000. However, if an estate was valued at less than $500, then it was not subject to any tax regardless of relation to the decedent.

As a reference point, $500 in 1901 is equivalent in purchasing power to about $15,317 in 2020 according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics consumer price index. The $10,000 exemption is equivalent to $306,152.23

The first major amendments to Nebraska’s inheritance tax occurred eighty years after its creation in the 87th Nebraska Legislature. Senators expressed concerns about the inheritance tax’s structure and how it contradicted aspects of the federal estate tax law. Transcripts from multiple legislative sessions and committee hearings show examples of past officials whom either believed the tax needed to be repealed due to its archaic structure or needed to be amended to increase the tax’s efficiency.24 The result was two major amendments that (1) exempted property transfers to surviving spouses and simplified the system of gift reporting, and (2) rectified problems of liens imposed upon spouses.25

The late former state Sen. Peter Hoagland, who later went on to serve as the U.S. Representative for Nebraska’s 2nd Congressional District, spoke on the inheritance tax on April 7, 1982, during floor debate on his LB480 from the 87th Legislature,

“When Senator Beyer and I introduced this bill, we were concerned not only about the inheritance tax which was originally enacted in 1901 which is basically an antiquated tax with an antiquated collection system, and which has been superseded in many respects by all the subsequent forms of taxation that has since been developed at the state and federal level. In 1901, when the county inheritance tax was adopted, there was no state sales or income tax, there was no federal income tax. There really in the last 80 years, needless to say, have been enormous changes in the taxation system.”26

In addition to these amendments, the floor debate within the 87th Legislature focused on how much money was being collected by counties from the tax.27 The point of contention was that since the tax’s enactment in 1901, the counties had been given other means of raising revenue, and the amount from the inheritance tax was a small portion of the county’s overall revenue. The opposing view was that the revenue from the inheritance tax provided great improvement opportunities for the counties, and without this tax, the counties would have to increase their real estate taxes. The ultimate decision on this matter resulted in removing the original descriptions of the ways the counties could spend the proceeds of the inheritance tax.

Another result of this legislation was a significant reduction in legal fees associated with the “inheritance tax determination” and the cost of administering the county inheritance tax. Though it resulted in some loss of revenue to the counties, the exact amount was unable to be calculated at the time.28

The next big push for changes to the inheritance tax came during the 100th Legislature in 2007. This happened to be the same year when Nebraska repealed its estate tax.29 Legislative Bill 502 was intended to be revenue neutral. It sought to reduce the revenue collected from the inheritance tax paid by immediate family members and to increase the amount paid by more distant relatives or other non-related beneficiaries.30 According to Nebraska Association of Counties (NACO) data from 10 counties cited at the hearing,

“The Class I which is immediate family members in these test counties represented about 42% of the revenues received in inheritance tax. Class II which is remote relatives was about 48%. And Class III, those that are not related, was about 9%.”31

While there was substantial floor debate on the bill, it ultimately passed. The major takeaway was that nobody knew exactly what rate or exemption change would keep the tax revenue neutral because there is no formal reporting of the tax or how it is used by the counties.32

The last major attempt to change the state’s inheritance tax was in 2012. During Gov. Dave Heineman’s State of the State address, he proposed a complete repeal of Nebraska’s inheritance tax through a gradual phase out to give the counties time to adjust.33 Echoing the same historical arguments, this idea was met with opposition from many county officials, who argued that without inheritance tax revenues for county operations, real estate taxes would be increased.34

As a result, two bills were filed in the 102nd Legislature to satisfy the governor’s request. LB970 was a total repeal of the inheritance tax, and LB1102, which would increase the exemptions and lower the rates over time. Both bills were unsuccessful in the Legislature.

In more recent years, Sens. Thomas Hansen and Tom Carlson introduced bills to eliminate35 or reduce36 the tax during the 103rd Legislature in 2014. Following in the 104th Legislature, Sen. Laura Ebke introduced LB93637 in 2016, which created a generous exemption and created a flat 1% tax on all heirs.

The aforementioned reforms and attempts at reform are just a sampling of what has occurred in Nebraska related to the inheritance tax. There have been multiple other bills filed to adjust the tax that have been unsuccessful. While the Legislature has amended the tax, there have also been numerous lawsuits related to Nebraska’s inheritance tax over the last 120 years.38 However, the result is that most of the law’s substance and purpose remains unchanged today from its original version in 1901.

Fiscal and Economic Considerations

Historically, many scholars have argued against inheritance taxes on a multitude of economic premises. The most accepted argument is that the tax falls on capital, which ultimately diminishes future production and reduces economic growth. Those arguing in favor of the tax focus on wealth distribution, arguing that the tax can break up large fortunes. Interestingly, both sides of this argument would disagree with the idea that a progressive inheritance tax should be levied at higher rates as more distant relations receive an inheritance. Those in favor of inheritance taxes traditionally believe progressive rates should be applied to the amount of wealth or property received and not based solely on familial relationships.

Wealth redistribution was not the only original motivation for inheritance taxes, though. The tax largely pre-dates income taxes or sales taxes, and one of the historical rationales for the tax in Nebraska was that an additional revenue source was needed to defray losses from personal property that had escaped taxation. For most of the 20th century, personal property tax was owed by the general public, in addition to businesses, but tax avoidance was commonplace.

By enacting an inheritance tax, policymakers reasoned they had a means of collecting tax on personal property that went unpaid in the past, because the personal property could not be concealed as easily during the probate process. This concern, however, became moot when the state stopped collecting personal property tax on individuals as a result of Nebraska’s 1967 tax changes.

In modern tax analysis, the inheritance tax has been found to reduce investment, discourage business expansion, and can sometimes drive wealthy taxpayers out of the state. When high net worth individuals leave states, not only does the local community miss out on the one-time inheritance tax revenue, but the state misses the revenue from other taxes that might have been collected during their lifetimes.39

It should be noted that past literature has evaluated the inheritance tax as a state, and not local, revenue source. While most, if not all, of the economic literature is still relevant in this situation, it does change the analysis from a fiscal aspect. Many of Nebraska’s counties are extremely rural, with little retail activity. In these remote areas of the state, the ability to shift away from the inheritance tax toward local revenue sources besides property tax may be more limited than in the more urban areas. This is why any reform options must weigh the impact to counties.

Below are the main economic and fiscal concerns related specifically to the inheritance tax.

Avoidance

Many individuals, mostly those expecting to leave a sizable legacy to their heirs, employ sophisticated estate planning techniques to limit their future tax liability. This process not only limits the amount of tax revenue that is collected by governments, but also imposes other costs such as the time and resources spent on estate planning, and in economic opportunities foregone to reduce future tax exposure.40 These costs have been known to be substantial, and are economically inefficient, as they reduce wealth without increasing government revenues.

Some of the most common avoidance techniques are making tax-advantaged gifts and transfers as well as shifting assets and investments. For example, under a shifting technique, the original owners may bring children on as owners of a home or co-investor in a business, which allows the profits to accrue directly to the intended heir, effectively bypassing the tax. Both techniques encourage inefficient resource allocation and have a negative impact on economic growth.

Because these estate planning techniques are normally used by wealthy individuals, those of lower- or middle-incomes are usually the most affected by the tax. Because their amount of property may require relatively less management, they would not likely be as motivated to conduct estate planning or hire an outside planner.41

Nebraska Specific Avoidance Techniques

Another avoidance method is the failure to report transfers. There are three broad categories of property: real property (real estate), tangible property (furniture, jewelry, etc.), and intangible property (stocks, bonds, insurance policies, etc.). With regards to Nebraska’s inheritance tax, tangible and intangible property are the most difficult assets to track. As a result, if a decedent did not own any real estate in the state of Nebraska, then there is no concrete way to track the transfer of their property at death, and it frequently goes unreported.

Another way Nebraskans have been instructed to avoid the inheritance tax on real property is by creating a foreign limited liability company (LLC). If an individual decided to transfer their real property into a foreign LLC, the property interest no longer belongs to the individual, but to the company, effectively sheltering the assets from the inheritance tax.42

In fact, this is such a well-known method of avoidance that multiple publications in legal journals have detailed how family farming operations can shield their assets from the burden of state inheritance taxes. Nebraska is so well-known for taxing small farmers with its inheritance tax that the Drake Journal of Agricultural Law used Nebraska as an example in an article titled “Dodging the tax bullet: the use of foreign limited liability companies by retired farmers to limit state inheritance tax liability for the next generation of small farmers.”43

Those choosing to stay in Nebraska and whom have the foresight to plan for death will go through estate planning. These legal tax avoidance strategies ultimately create dead-weight losses that reduce economic efficiency and, in some instances, break up farms and family-owned businesses.

Reliability of Revenue from the Tax

The tax collections from the inheritance tax often fluctuate. In Nebraska, where the tax is collected at the county level, the death of one very wealthy person can dramatically affect collections. Because of this, the inheritance tax is difficult, if not impossible, to forecast. This is partially why the counties in Nebraska treat the revenue from the inheritance tax as a cash reserve. Using long-term averages is the best method for forecasting revenues for this type of tax.

For example, over the last 5 years in Banner County, its inheritance tax revenue equates to an average of 1% of fiscal year receipts. However, in 2016 this jumped to 18.3%. A similar situation occurred in Loup County in 2019, when inheritance tax revenue was 58.7% of total county receipts, where their normal average is around 3%.

This occurs less frequently in larger populated counties, but windfalls from wealthy individuals still occur. Measuring inheritance tax as a percent of total county receipts, Dodge County received 10.6% in 2019, where their average is 2.8%, Saline County received 17.7% in 2018 with an average around 5%, and Dawson County received 27.2% in 2015, with an average of 3.7%.

Compliance and Administration

The probate system for disposing of assets at death requires an accounting of the decedent’s assets. Because Nebraska is the only state to have ever imposed this tax as a local government revenue source, each county administers the tax in different ways. Nebraska also has no central taxing authority, meaning the inheritance tax is administered by the county or probate court of the county where the estate’s administration is being conducted.44 Therefore, while the inheritance tax has no administrative burdens on the state, its implementation and documentation lacks standardization.

Interstate Competition

One main cause for the trend to eliminate or reduce inheritance taxes is the role of interstate competition. Wealthy taxpayers can easily avoid state taxes by establishing residence in a state where tax laws are more favorable, such as snowbirds moving to Arizona or Florida. However, Nebraska inheritance taxes can legally be imposed on real and tangible property located within the state, even if the taxpayer lives in another state. This does not affect the value of a wealthy person’s estate, which today is typically intangible property—stocks, bonds, and cash—that is only taxable to the state of residence.

There have been many academic studies that have found evidence that high state inheritance taxes discourage migration into a state.45 In fact, one study found that a 1% increase in a state’s average inheritance tax rate is associated with a 1.4 to 2.7% decline in the number of federal estate tax returns filed in each state, with estates over $5 million particularly responsive to rate differentials.46 In response to those that claim tax competition based upon the inheritance tax is not occurring, one study found “that a 10% decrease in the estate/inheritance tax share of a ‘competitor’ state leads to between a 2.2 to 4.3% decrease in the state’s own estate/inheritance share”—confirming that tax competition on death taxes is taking place.47

Nebraska Inheritance Tax Revenues

Because the local revenue received from the inheritance tax functions like a county cash reserve, it is administered and spent in different ways across all 93 counties.48

Statewide Analysis

On a statewide basis, the inheritance tax collections have ranged from $18.9 to $73.3 million since 1993 ($33.7 to $74.5 million if adjusted for inflation into 2020 dollars). It is noticeable from Figure 2 that the tax rate for Nebraska’s inheritance tax changed in 2007. Prior to this time, the tax collections were relatively flat and increased substantially afterward.

Part of this is due to the exemption amount and tax rates staying the same while inflation erodes the value of the dollar. This same concept can be observed in income tax analysis, where bracket creep can occur. Inflation can push taxpayers into higher income tax brackets, resulting in an increased tax burden. To prevent this, the Legislature adjusts Nebraska’s state income tax brackets to inflation, but has not done so with the inheritance tax.

When Nebraska originally set the exemption at $10,000 in 1901, it was considered a substantial amount of money (approximately $306,000 today). Keeping the exemption the same until 2007, when the most generous exemption was raised to $40,000 (approximately $50,000 today), has resulted in significant bracket creep.

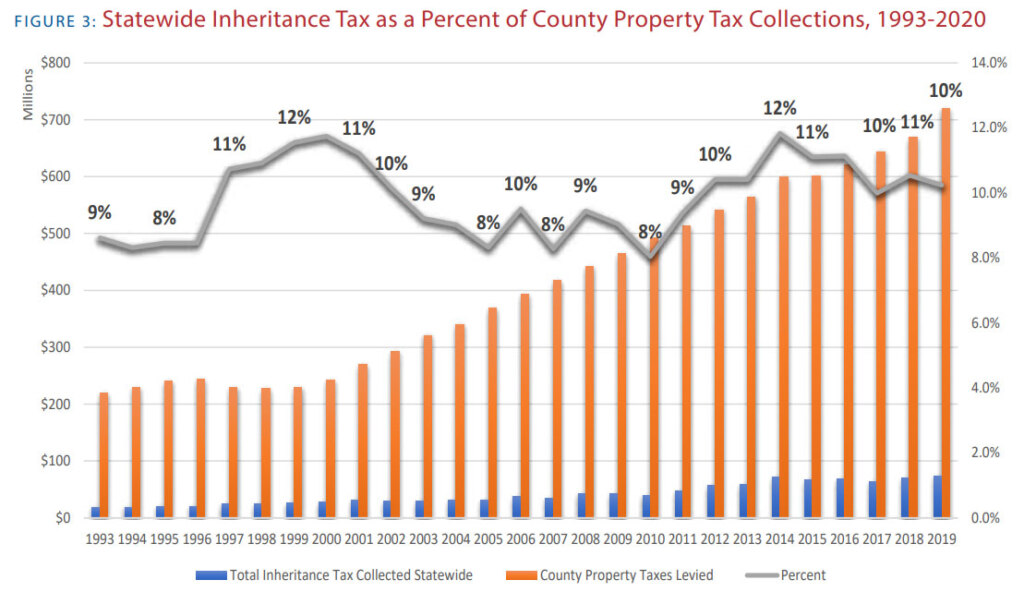

Many of the arguments against removing the inheritance tax stem from the need for local revenue or the fear that property taxes will increase if the inheritance tax is reduced or repealed. Counties receive many sources of revenue, which include property taxes, motor vehicle taxes, occupation taxes, fees, state aid, etc. However, due to Nebraska’s lack of local government financial reporting standards, the exact tax revenues for each county for these years are unavailable. That is why Figure 3 is measured as a percent of property tax collections statewide, to give a very liberal value for what the impact to the counties would be if the inheritance tax were to be repealed.

County Level Analysis

Each county in Nebraska collects their own inheritance tax and uses it for their own purpose. Some of these counties use the funds annually while others hold onto the funds and make one large disbursement for a major project. Currently, the state has no administrative role over the tax, which is one reason for its lack of reporting. Thanks to public records requests, hundreds of hours reviewing county audits and budgets, along with information from the Nebraska Association of County Officials and the Nebraska Auditor of Public Accounts, this paper has some county level data to provide. For the totals collected by each county in each fiscal year since 1993, please see Appendix 1.

Since fiscal year 1993, there are two counties that have either had the most collected or the least in the entire state over the nearly 30 years of data. Douglas County, the state’s most populated, has had the highest amount collected from the tax, with the most ever collected in a single year reaching $16.2 million in fiscal year 2018. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Arthur County, the state’s least populated (est. population 463 people), holds the record for the least collected in a single year, with fiscal year 2019 producing $0 and the year before only generating $74.

Table 6 shows us the average collections for each county, which gives a very different picture when evaluating the impact any changes this tax would have to county finances. As expected, the least populated counties in the state collect the least in inheritance tax dollars while the larger populated counties collect the most.

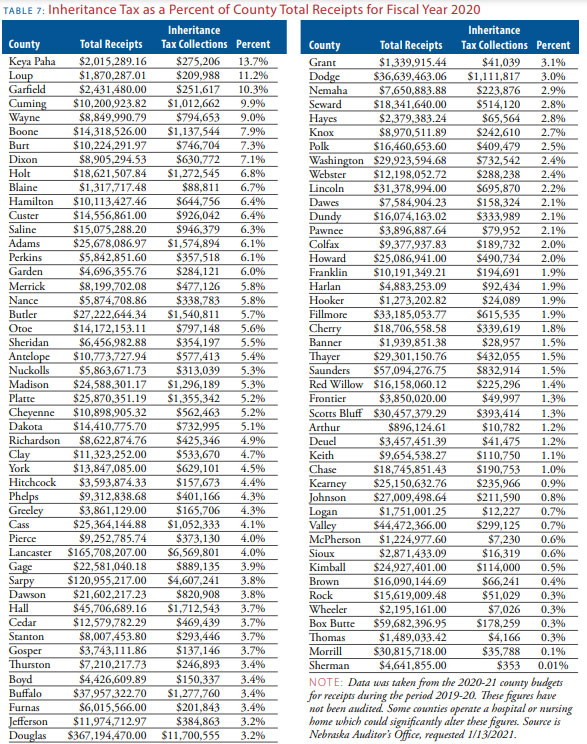

One of the most frequently asked questions during legislative hearings on reforms to the inheritance tax is what percent of county revenue comes from the inheritance tax. In Table 7, each county’s total receipts (revenues) for fiscal year 2020 is compared to the same year’s inheritance tax collections.

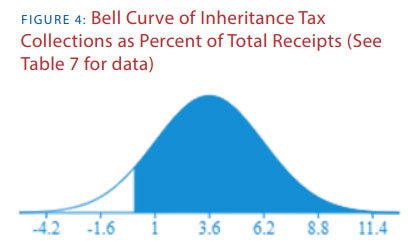

The range of inheritance tax collections to total county receipts is from 0.01% in Sherman County to 13.7% in Keya Paha County. The average (mean) statewide is 3.6% with a standard deviation of 2.6%. This tells us that the top two counties, Keya Paha and Loup are extreme outliers, and every county with a value above 6.2% and below 1% is outside one standard deviation from the mean. This applies to the bottom 14 and the top 13 counties.

The data is illustrated in a normal bell curve distribution. From this, we can see that for FY2020, seventy counties fell within one standard deviation of the mean, or inheritance tax collections were between 1% to 6.2% of total receipts. While the mean and standard deviation change each year, this snapshot of FY2020 gives a general estimate of what counties are relying on annually from the tax. In raw numbers, 14 counties were within two standard deviations from the mean (8 above and 14 below) while only one was 3 standard deviations above the mean. What this distribution shows is that while there are outliers of county inheritance tax receipts, most counties tend to collect 3-4% of their tax receipts from the inheritance tax.

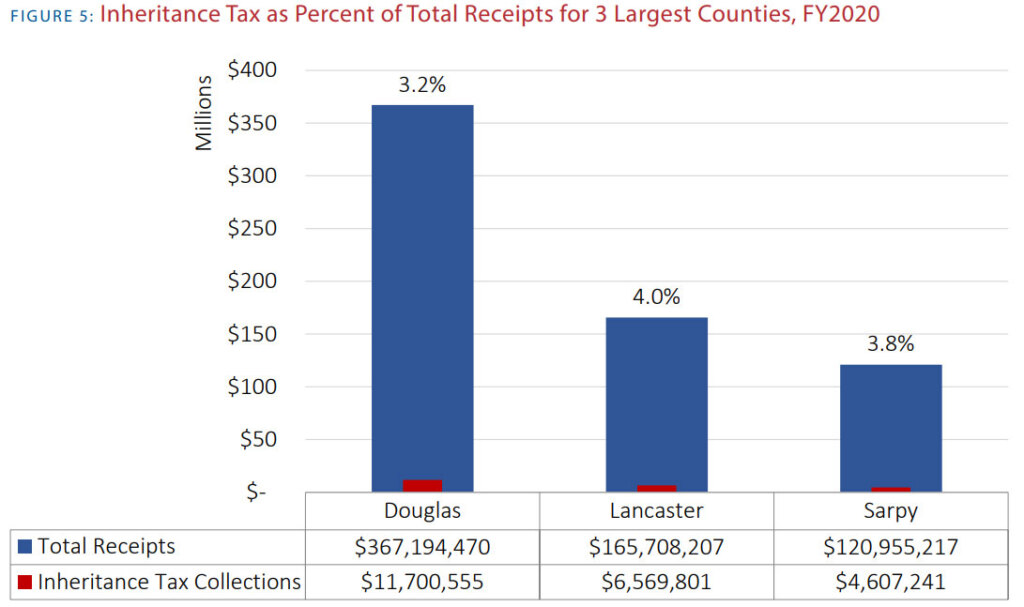

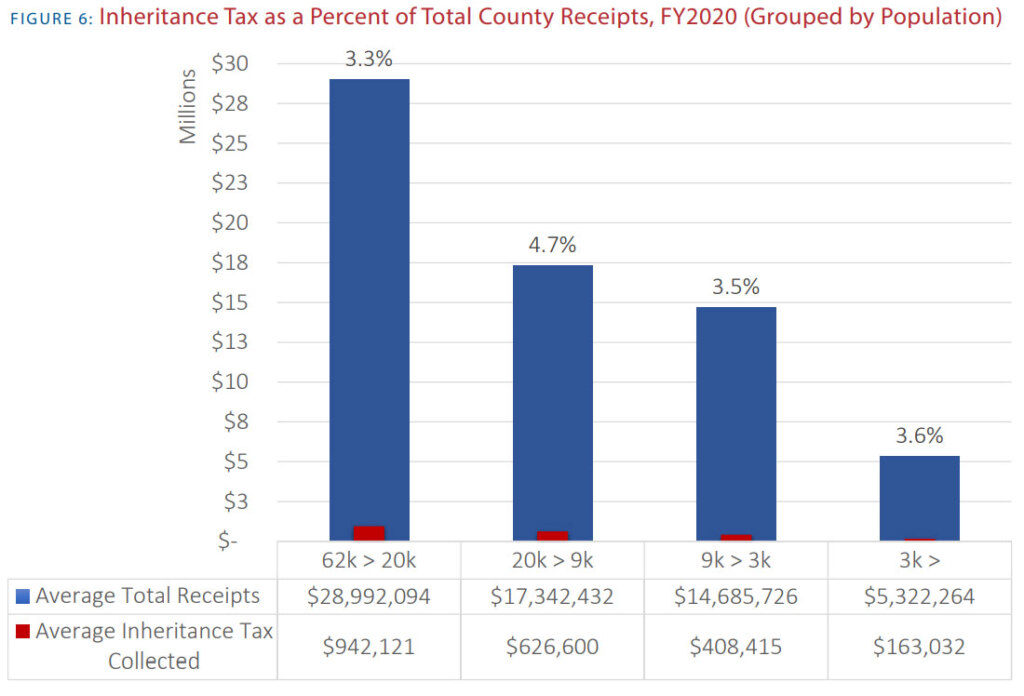

Because Nebraska has such varied population centers across the state, it is important to know how this tax affects counties from a population stance. Figure 5 looks at the three largest counties in the state and compares their total county receipts to total inheritance tax collections for FY2020. Figure 6 uses the same methodology yet groups counties according to population. The exact amounts used for the calculation are included in the figures.

Reform Options for Nebraska

The following are reform options that would be appropriate for Nebraska’s inheritance tax.

Repeal or Phase Out the Inheritance Tax

While the ideal reform option is the eventual repeal of the inheritance tax with a gradual phase out to allow counties time to adjust, history has shown us the opposition to this reform option is very strong. Forward-thinking lawmakers have introduced bills for over 40 years trying to repeal the inheritance tax, but none have been successful. Because of this situation, other reform options have been suggested in this paper to make the tax less burdensome and to modernize Nebraska’s tax code.

Reduce the Top Rate and Consolidate Tax Brackets

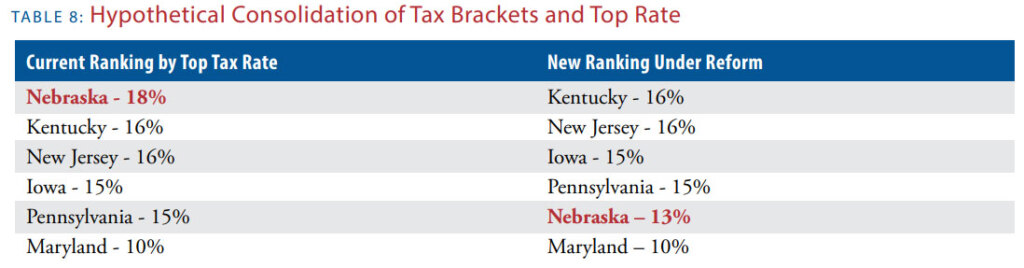

Right now, Nebraska has the highest rate for inheritance taxes nationwide at 18% for the Class 3 inheritors—those who are not related to the decedent. According to past testimony from NACO, the third bracket accounts for only 9-10% of the total amount collected under the tax. Consolidation of the Class 3 and Class 2 brackets (distant relatives) for the tax should be combined, creating a two-tiered tax with a top rate of only 13%, which is Nebraska’s current rate for Class 2 recipients. This reform would drop Nebraska’s top inheritance rate to the second lowest in the country, just behind Maryland’s top rate of 10%. If the reform proposed by Sen. Robert Clements in LB310 during the 107th Legislature of 2021 is enacted, then Nebraska’s top inheritance tax rate would be the lowest in the country at 9%.

Remove Probate Provisions

It is difficult to obtain the information on the amount collected by each class without going through each probate case individually. In addition, the cost to the beneficiary to take the estate through probate can sometimes equate 1-2% of the total inheritance, thus adding another regulatory-type tax onto the beneficiary.

A useful reform to the current system would be to move the inheritance tax out from under the court system and put it under the County Treasurer. This would simplify the system, requiring the beneficiary to only complete a form instead of having to hire an attorney. Standardizing this process would make reporting much easier and transparent.

A Statewide Reporting Requirement

For decades, policymakers have wondered how much revenue the inheritance tax collects, and how much is collected under each class tier and tax rate. NACO has tried to compile this information for the Legislature over the last few decades, but they have admitted it is time-consuming and not possible to get accurate information for all 93 counties.

Each county should remit to the state the amount of the tax collected in each tier to the Department of Revenue or the State Auditor. This will make data available to lawmakers who might want to consider how to adjust the inheritance tax rates in the future. The state department charged with this task should aggregate all the information and issue an annual report to the Legislature.

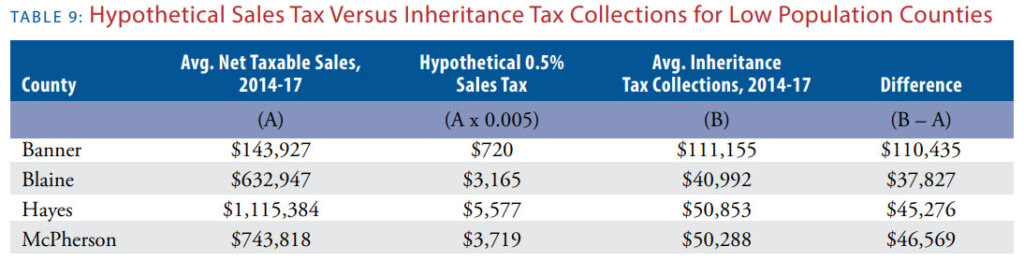

Allow County Level Sales Tax as a Replacement

Under current Nebraska law, a county sales tax can only be imposed on taxable sales within the county, but not within the boundaries of any city that also imposes a city sales tax.49 One possible reform could be to change state law to allow counties to collect sales tax within city limits, in addition to city taxes, if the county sales tax is approved by voters. This revenue stream could replace the inheritance tax and would be a more reliable source of revenue for the counties.

However, it should be noted that some counties have very little retail activity and taxable sales within their jurisdictions, such as Banner, Blaine, Hayes, and McPherson counties. So, while this is a viable reform option for the more populated counties in Nebraska, it is not a solution for every county.

Exempt Children Under the Age of Majority if Parents or Direct Guardians are Decedents

In his Wealth of Nations50, Adam Smith mentioned that it was inappropriate to impose an inheritance tax upon the death of a parent or guardian when the decedent’s children were still minors. If this situation were to occur, the loss of the parent or guardian may already result in a considerable reduction of future financial support, and the children should not be subject to any further reduction of their parent’s or guardian’s possessions.

“That tax would be cruel and oppressive which aggravated their loss by taking from them any part of his succession.”

– Wealth of Nations

Nebraska’s inheritance tax law should exclude minor children from the 1% tax imposed on them if their parents or guardians leave them any inheritance. The fiscal impact of this should be negligible since most people die at an advanced age.

Conclusion

Several proposals have been introduced in the Legislature in recent years to address the inheritance tax. The fact remains that Nebraska’s inheritance tax is chiefly a tax on families. And since the assets to be inherited were acquired with after-tax income, in the case of Nebraska’s excessive property tax, it is appropriate to describe the inheritance tax as a triple tax, since the decedent must have also been paying the requisite property taxes for the land to be inheritable.

The inheritance tax is contrary to the idea of tax modernization because it is a holdover from a tax system and economy that no longer exists. Given that there is no sign that other states will reinstitute their inheritance taxes in the 21st century, Nebraska should recognize that it is in the state’s interest to repeal the tax, if not immediately, then over a reasonable period of years.

Records show that although many Nebraska policymakers understood the need for repeal, even in eras when the tax brought in a relatively minimal amount of revenue for counties, they also faced insurmountable obstacles in the Legislature.

If the removal of the inheritance tax is politically impossible due to the need for local revenue sources other than property tax, then Nebraska lawmakers need to look seriously at the tax’s most harmful effects and work to mitigate those features, so the tax is more efficient and less of an economic burden to families.

Those that support the tax’s progressive nature would do well to see that taxing an inheritance at a higher rate based on the relationship from the decedent is in direct opposition to wealth distribution policies. For example, a life-long domestic partner is not recognized as a legal spouse by the State, and this means their gift from the decedent is taxed at the highest rate.

Reforms are long overdue for this tax, as well as a uniform method of reporting the revenue generated from the tax. Making changes to the inheritance tax can help Nebraska create a tax system more aligned with the 21st century and may cause the state to be removed from Forbes’ list of places “not to die,”51 but most importantly, eliminating the barriers and frustrations the tax creates for families and businesses can make Nebraska a better place to live.

An appendix with additional county-level data and a copy of Nebraska’s original inheritance tax legislation is available in the PDF version of this report.

Endnotes

1. Ebeling, Ashlea (Jan. 15, 2021). “State Death Tax Hikes Loom: Where Not To Die in 2021” Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/ashleaebeling/2021/01/15/state-death-tax-changes-loom-where-not-to-die-in-2021/?sh=2a8cd43944cd.

2. Wagner, Richard (1993). “Federal Transfer Taxation: A Study in Social Cost”, Institute for Research on the Economics of Taxation Fiscal Issue No. 8. ; Walczak, Jared (July 17, 2017). “State Inheritance and Estate Taxes: Rates, Economic Implications, and the Return of Interstate Competition”. Tax Foundation Special Report No. 235.

3. Birmingham, Edward (1968). “Nebraska Inheritance and Estate Taxes,” Creighton Law Review 2, no. 2: 284-294

4. P.L. 107-16, § 531 and § 532. Generally, the maximum allowable credit was the lesser of the net tax paid to the State or the statutory ceiling of 26 U.S.C. § 2011(b) (a percentage of the taxable estate minus $60,000). Many States used the maximum credit allowed under § 2001(b) to constitute the State’s estate and/or inheritance tax.

5. LB367-2007 repealed the estate tax dying on or after January 1, 2007. Prior to enactment of LB367, Nebraska levied a graduated estate tax, beginning at 5.6 percent on estates of less than $100,000 and increasing to 16.8 percent on estates over $9 million.

6. Neb. Rev. St. § 77-2001.

7. West, Max (1908). The inheritance tax. Columbia University Press, the Macmillan Company, agents, pages 87-96

8. Pollack, Sheldon D. “Origins of the Modern Income Tax, 1894-1913.” Tax Lawyer, vol. 66, no. 2, Winter 2013, p. 295-330.

9. West, Max (1908). The inheritance tax. Columbia University Press, the Macmillan Company, agents, page 125.

10. Magoun vs. Illinois Trust and Savings Bank et al., 170 U.S. 283 (April 25, 1898).

11. West, Max (1908). The inheritance tax. Columbia University Press, the Macmillan Company, agents.

12. Oakes, Eugene E. “Development of American State Death Taxes.” Iowa Law Review, vol. 26, no. 3, March 1941, p. 459-460.

13. Oakes, Eugene E. “Development of American State Death Taxes.” Iowa Law Review, vol. 26, no. 3, March 1941, p. 468.

14. Nevada repealed their inheritance tax in 1925 and at the time Alaska was not a state.

15. For a more in-depth discussion of the controversy of the tax credit, see “The Federal Offset and the American Death Tax System” (1940) 54 Harvard Quarterly Journal of Economics, 566.

16. Luckey, J. R. (2011). “A History of Federal Estate, Gift, and Generation-Skipping Taxes”. Congressional Research Service, https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20110124_95-444_50e99c528a7f80c3b710d7d6a323e78ab8d399e2.pdf.

17. Michael, J. (Dec. 25, 2006). “State Estate, Inheritance, and Gift Taxes Five Years After EGTRRA”, State Tax Notes Special Report.

18. This was done by Florida in 1931, New York in 1930, Alabama in 1932, North Dakota in 1933, Oklahoma in 1935, and Arizona in 1937.

19. Oakes, Eugene E. “Development of American State Death Taxes.” Iowa Law Review, vol. 26, no. 3, March 1941, p. 469.

20. Michael, J. (Dec. 25, 2006). “State Estate, Inheritance, and Gift Taxes Five Years After EGTRRA”, State Tax Notes Special Report.

21. West, Max (1908). The inheritance tax. Columbia University Press, the Macmillan Company, agents.

22. Nebraska – 27th Session: 41-632; Laws 1901, c. 54, § 1, p. 414

23. https://www.in2013dollars.com/us inflation/1901?amount =500, accessed December 10, 2020.

24. Faulkner, B. J. (2012). The ugly stepsister inheriting the defects of Nebraska’s inheritance tax. Creighton Law Review, 46(2), p.288.

25. Floor debate transcript for the 87th Legislature, LB 480, page 8,921.

26. Floor debate transcript for the 87th Legislature, LB 480, page 10,443.

27. Floor debate transcript for the 87th Legislature, LB480, page 8,924.

28. Floor debate transcript for the 87th Legislature, LB480, page 10,444.

29. Aiken, David J. (2007). “2007 Legislature Repeals Estate Tax and Reduces Inheritance Tax”. Cornhusker Economics. 325.

30. Nebraska Revenue Committee (Feb. 28, 2007). “Transcript prepared by the Clerk of the Legislature [LB502]”, pg. 7-11, https://www.nebraskalegislature.gov/FloorDocs/100/PDF/Transcripts/Revenue/2007-02-28.pdf.

31. Nebraska Revenue Committee (Feb. 28, 2007). “Transcript prepared by the Clerk of the Legislature [LB502]”, pg. 8, https://www.nebraskalegislature.gov/FloorDocs/100/PDF/Transcripts/Revenue/2007-02-28.pdf.

32. Nebraska Floor Debate (March 28, 2007). “Transcript prepared by the Clerk of the Legislature [LB502]”, pg. 48-88, https://www.nebraskalegislature.gov/FloorDocs/100/PDF/Transcripts/FloorDebate/r1day53.pdf.

33. O’Hanlon, K. (Jan. 12, 2012). Heineman touts tax cuts during State of the State address. Lincoln Journal Star, retrieved from https://journalstar.com/news/state-and-regional/nebraska/heineman-touts-tax-cuts-during-state-of-the-state-address/article_ec405b3f-edaa-51f3-becc-0880ce4eebd2.html.

34. Hub staff (Feb. 14, 2012). Governor’s inheritance tax repeal gets early ‘no’ in Unicam. Kearney Hub, retrieved from https://kearneyhub.com/news/local/article_092d8fc8-573c-11e1-bade-001871e3ce6c.html.

35. Legislative Bill 812. 103rd Nebraska Legislature, second session, 2014, https://nebraskalegislature.gov/bills/view_bill.php?DocumentID=21836.

36. Legislative Bill 960. 103rd Nebraska Legislature, second session. 2014, https://nebraskalegislature.gov/bills/view_bill.php?DocumentID=22067.

37. Legislative Bill 936. 104th Nebraska Legislature, second session. 2016, https://nebraskalegislature.gov/bills/view_bill.php?DocumentID=28473.

38. Nebraska Revised Statutes Chapter 77-2001:2040

39. Walczak, Jared (2017). “State Inheritance and Estate Taxes: Rates, Economic Implications, and the Return of Interstate Competition”. Tax Foundation Special Report No. 235, https://taxfoundation.org/state-inheritance-estate-taxes-economic-implications/.

40. Walczak, Jared (2017). “State Inheritance and Estate Taxes: Rates, Economic Implications, and the Return of Interstate Competition”. Tax Foundation Special Report No. 235, https://taxfoundation.org/state-inheritance-estate-taxes-economic-implications/.

41. Aaron, H. & Munnell, A. (1992) “Reassessing the Role for Wealth Transfer Taxes”, National Tax Journal 45:2, pg. 134.

42. Faulkner, Brittany (2012). “The Ugly Stepsister – Inheriting the Defects of Nebraska’s Inheritance Tax.” Creighton Law Review, vol. 46, no. 2, p. 285-308.

43. Steger, C. S. (2010). Dodging the Tax Bullet: The Use of Foreign Limited Liability Companies by Retired Farmers to Limit State Inheritance Tax Liability for the Next Generation of Small Farmers. Drake J. Agric. L., 15, 167.

44. Committee on State Death Taxation, Probate and Trust Division. (1979). Survey of state death tax systems and of selected problems of double taxation of real property interests. Real Property, Probate and Trust Journal, 277-400.

45. Voss, Gunderson, & Manchin, “Death Taxes and Elderly Interstate Migration,” Research on Aging Vol. 10:3 (Sept. 1988), 420-450; Conway & Houtenville, “Elderly Migration and State Fiscal Policy: Evidence from the 1990 Census Migration Flows,” National Tax Journal 54:1 (2001), 103-23.

46. Bakija, J., & Slemrod, J. (2004). Do the rich flee from high state taxes? Evidence from federal estate tax returns (No. w10645). National Bureau of Economic Research.

47. Conway, K. S., & Rork, J. C. (2004). Diagnosis murder: The death of state death taxes. Economic Inquiry, 42(4), 537-559.

48. Faulkner, Brittany J (2012). “The Ugly Stepsister – Inheriting the Defects of Nebraska’s Inheritance Tax.” Creighton Law Review, vol. 46, no. 2, p. 285-308. See testimony from NACO’s Larry Dix said, “Inheritance tax is to the counties what the Cash Reserve is to the state.” Testimony on LB970 (Jan. 26, 2012), pg. 42, https://www.nebraskalegislature.gov/FloorDocs/102/PDF/Transcripts/Revenue/2012-01-26.pdf.

49. Gage County is the exception to this rule, see Nebraska Department of Revenue press release (Sept. 18, 2019) “Gage County Imposes a Local Sales and Use Tax Rate of 0.50% -Effective January 1, 2020”, https://revenue.nebraska.gov/sites/revenue.nebraska.gov/files/doc/news-release/pad/2019/Gage_Co_Imposes_Local_Sales_and_Use_Tax_Rates_January_2020.pdf.

50. Smith, A. (1776) Wealth of Nations, chapter ii, pt. ii, appendix to articles 1 and 2.

51. Ebeling, A. (Jan. 15, 2021). “State Death Tax Hikes Loom: Where Not To Die in 2021” Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/ashleaebeling/2021/01/15/state-death-tax-changes-loom-where-not-to-die-in-2021/?sh=2a8cd43944cd.

Are you one of the 78% of Nebraskans who agree it’s time to lay the county inheritance tax to rest? Sign the petition to tell the Unicameral to eliminate this outdated and inequitable tax on Nebraska families.

Sign The Petition

End Nebraska's Inheritance Tax

Simply fill out the form below to sign the petition.

Learn More >