2019-2020 Nebraska Occupational Licensing Review

Introduction

Much has changed since our 2018 review of Nebraska’s progress on occupational licensing policy and reform.

The first year of licensing reviews growing out of LB299, Nebraska’s Occupational Board Reform Act, were completed in 2019. Committees of the Unicameral reviewed 26 individual licenses across eight of the standing committees.

Several of the other committees—either because of being short-staffed, being heavily engaged in other reports, or having few licenses under their jurisdiction—deferred reviews until 2020. A look at the reviews underway in the early autumn of 2020 suggests that they will be getting caught up—at least 40 licensing reviews are currently being worked on during the 2020 legislative interim.

The view of those seeking licensing—and those sitting on committees considering licensing-related bills—has changed as well. Two examples demonstrate the changing climate:

- In 2019, one professional organization considering the possibility of seeking legislation to license a profession contacted the Platte Institute before having a bill introduced, assuming that we would probably oppose any new licensing. After several extended conversations, we were able to help them come up with a solution using a “less restrictive” means of regulation which enabled the industry to expand its practice.

- In both 2019 and 2020 hearings in which Platte Institute staff testified on some question of occupational licensing, legislators were heard to ask the specific question: “How does that impact the LB299 process?”

Continuing efforts to make it easier to work in Nebraska is critical. Many states are adopting occupational licensing changes, and Nebraska must keep up to remain competitive in retaining and attracting the most valuable resources to our state: human capital.

A Brief History of Licensing

Classically liberal, conservative, and libertarian economists have argued for over half a century that excessive occupational licensing is a danger to labor markets. During that time, we’ve gone from roughly 5% to 23% of workers in the workforce who must be licensed by the state.[i]

The movement to reconsider policy attitudes about occupational regulation was given a boost by the Obama administration, which in 2015 released a study calling for reforms compiled by the Treasury Office of Economic Policy, the Council of Economic Advisers, and the Department of Labor.[ii]

As pointed out in our 2018 report:

A wide variety of research organizations and industry groups have reached the conclusion that while in some cases, licenses may be needed to protect the public, in many instances, occupational licensing is a burden to both the licensee and the consumer.

In the two years since that report, the number of policy organizations, academic research institutes, and “public officials’ associations” (like the Council of State Governments and National Conference of State Legislatures) paying attention to occupational licensing in the states has grown almost exponentially.

Groups like the National Conference of State Legislatures and academic-based institutes like the Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation[iii] are now tracking up-to-date data on licensing-related legislation around the country. They and others—like the Institute for Justice and the Mercatus Center at George Mason University—have not only been keeping up on current legislation in the arena but have also started compiling records on requirements for licensure in many occupational areas across the 50 states.

Licensing Around the Country

As the national discussion on occupational licensing reform has continued, states have looked at several ways of reforming their occupational regulatory structure. Those methods fall into a few general categories:

- “Sunrise/Sunset” Reviews. Review bills create a framework for states to regularly review licenses in their jurisdiction, to determine whether the licenses are still needed in their current form, or whether they could be changed to something less restrictive or eliminated. This approach was used in the first comprehensive efforts to re-think occupational licensing in the states. Nebraska was an “early adopter” of this effort in April of 2018.[iv] Ohio followed later that year, and several other states have enacted similar legislation.

- “Universal Recognition.” Universal recognition (sometimes referred to somewhat incorrectly as “reciprocity”) is the state acknowledging the experience or licensing workers bring from another state for purposes of licensing in their own state. The underlying assumption of Universal Recognition is that individuals don’t lose their experience and training just because they’ve crossed state lines, and states seeking to welcome individuals into the labor force should reduce the need to jump through hoops with more training and testing.

Many states have created frameworks of modified Universal Recognition for at least some occupations—for those who are active-duty military or military families. Others, like Arizona, Pennsylvania, Iowa, New Jersey, Missouri, and Utah, have passed laws welcoming workers from other states to come work in their state.

During the spring of 2020, many governors created—through executive order—temporary Universal Recognition for workers in the health care industry, to make rapid-response to potential COVID-19 outbreaks easier.

- “Licensing Board Membership.” A new approach that states like Arizona have started to look at is changing the makeup of their state licensing boards.[v] The goal with these efforts is to shift the balance of power on the boards from those who are practitioners of the occupation (who may be subtly self-interested) to lay members of the public, representing the interests of the consumers of services.

States have also taken “reactive and piecemeal” approaches—sometimes in conjunction with the methods above—to do away with, or significantly change, individual licenses. Standalone bills have also introduced criminal justice and “second chance” components to licensing reforms, or as components of more comprehensive legislation, to reduce recidivism through economic opportunity.

Occupational Licensing in the 106th Nebraska Legislature

2019 Occupational Board Reform Act Reviews

The interim of 2019 marked the first year of licensing reviews growing out of 2018’s Occupational Board Reform Act (LB299).

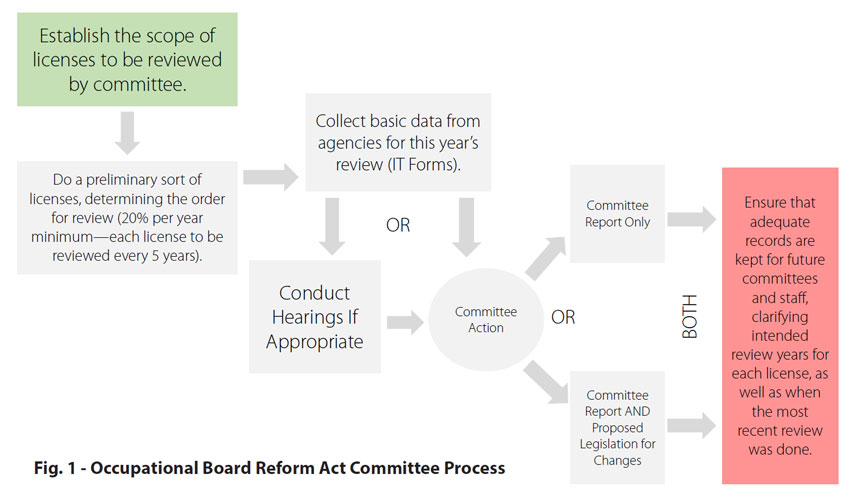

The process for the reviews looks something like the flow chart in Figure 1.

Making structural changes to occupational licensing in our state will depend on standing committees taking these review processes seriously and not leaving out the last step, which is maintaining records of licensing reviews and holding committees accountable for revisiting the reviewed license within the following five years.

Surveys and reports for the Occupational Board Reform Act reviews are now available on the Nebraska Legislature’s website under the Committees section.

In 2019, eight of the twelve standing committees having any identified licenses under their jurisdiction conducted reviews of at least one license.

Four committees, Health and Human Services (HHS), Transportation and Telecommunications, Revenue, and Urban Affairs, conducted none. For the latter three, there are few licenses under the committees’ jurisdiction, and the decision was made to defer a year due to other concerns.

In the case of HHS, the committee found itself short-staffed and amid some significant child welfare studies. The committee has now re-staffed, and it appears that it will be conducting more reviews in the 2020 interim to catch up.

While nothing earth-shattering was discovered in the 2019 reports, a few things might be worth noting.

First, licensing of all types seems to incline toward layering. The Education Committee report, for instance, revealed three different types of permanent (and one temporary) administrative certificates. Multiple insurance-related licenses were found in the Banking and Insurance Committee Report. Licensing is not just a binary condition of “licensed or not licensed.” Rather, occupational regulation—once created–has a tendency to subdivide, creating niche positions and services that end up being licensed separately.

Take, for example, mental health practitioners in Nebraska. The Department of Health and Human Services licenses: Provisionally Licensed Mental Health Practitioners (PLMHP), Provisional Certifications as a Master Social Worker (PCMSW), and Licensed Independent Mental Health Practitioners (LIMHP); and then certifies (with title protected) Certified Professional Counselors, Certified Marriage and Family Therapists, Certified Master Social Workers and Certified Social Workers. One way of reducing occupational barriers might be to move toward a base level form of credentialing in these fields, much the way physicians are licensed as “physicians and surgeons,” and then allow additional credentials to be defined by private certifications and acceptance by employers. A psychiatrist, a surgeon, and a family physician all have the same license in Nebraska. Their specialties then are defined by their board certification and accepted by hospital and employer credentialing, not defined by added state licensing levels.

A second thing that might be noted as the result of the 2019 reviews is that at least some state licensing grows out of mandates by the federal government. Livestock Dealers in Nebraska, for instance, are an outgrowth of the national Packers and Stockyards Act.

Finally, “occupational licensing” is a broad term. In the case of Livestock Dealers, for instance, it would be more accurate to describe the credential as a business registration rather than an individual license. As the Legislature continues to move through the roughly 200 licenses to be reviewed in Nebraska, it seems likely that many of these occupational licenses could be re-categorized under less restrictive forms of occupational regulation.

Without a doubt, none of these discussions would take place, nor would questions be raised about the need for some licenses, without a regular review process.

New Bills

In the 106th Legislature, 26 bills were identified as having a direct occupational licensing component. Most of those bills would have made it easier for Nebraskans to receive the necessary credentials to work in the occupation of their choice, although a few would have increased regulations.

The Platte Institute weighed in on most of the bills related to occupational regulation (see the table to follow). A few highlights:

LB1187—Universal Recognition

Nebraska’s first attempt at adding to comprehensive reform—through LB1187’s Universal Recognition provisions—was unsuccessful. Sen. Andrew La Grone was the sponsor of that legislation, introduced in January 2020. While it appeared to have a critical mass of support on the Government, Military, and Veterans Affairs Committee, the timing of introduction and a relatively late hearing—combined with a lack of priority designation—meant that the committee did not advance it to General File during the short session.

In retrospect, with the emergency recess of the 2020 session due to COVID-19, and the return of the Legislature in mid-July, it seems likely that the chances of LB1187 moving through the Legislature would have been slim, even if it had been advanced from committee.

We anticipate that the bill will be reintroduced early in the 107th Legislature, which begins in January 2021.

LB1068—Interior Design Voluntary Registration Act

This bill, while it advanced from the committee, ultimately didn’t have time to be heard on the floor of the Legislature. Sen. Megan Hunt was the introducer.

This bill took a unique—and Occupational Board Reform Act friendly—approach to a licensing problem. In the current building permit framework in Nebraska, only licensed architects and engineers can “stamp” building plans. Interior designers wanted to be able to stamp design plans for interior work that they do, without having to be associated with (or pay) an architect or engineer to do it for them.

This bill would have allowed the state to recognize interior designers who had taken advanced coursework and been certified by a national interior design board to voluntarily register for a stamp to be issued by the state. Unlike an occupational licensing law for interior designers, the bill would not have limited the ability of other practitioners to use the term “interior designer,” nor would it have required interior designers to complete that coursework if their practice of the occupation didn’t demand the use of a stamp.

We expect that the bill will be reintroduced in the 107th Legislature.

LB607—Nail Technology

Sen. Mark Kolterman introduced LB607. The bill had several purposes. The first was to allow for “Temporary Body Art Facilities” and “Body Art Guest Artist” licenses.

The second element would have changed the definition of “nail technology.” Currently, manicures and pedicures on natural nails are not regulated. Hence, Nebraska has many salons—often operated by immigrants—offering those services. The bill would have swept up manicure and pedicure services into the domain of regulation by the Board of Cosmetology, Electrology, Esthetics, Nail Technology, and Body Art–and likely increased the cost to entrepreneurs in this field.

The bill was passed, but vetoed by Gov. Ricketts, who noted:

“Entrepreneurs, many who have recently immigrated to our state, work in this profession. The regulatory burdens placed upon them in LB607 do not seem warranted when weighed against the harm that the bill intends to prevent. A better practice would be to require a less burdensome state registration system for natural nail manicurists and pedicurists.”[vi]

This bill will likely be amended to address some of the governor’s concerns, and reintroduced in 2021.

LB347—Exempt Reflexology from the Massage Therapy Practice Act

Sen. Dave Murman was the introducer of this bill. Reflexology is a personal care service in which a practitioner uses their hands to apply pressure to specific points on the feet, hands, and outer ears. The practice is part of an ongoing dispute about the need for licensure and how it should be licensed.

LB347 would have exempted the practice of reflexology from Massage Therapy regulation. Currently, only licensed massage therapists may provide reflexology services in Nebraska. However, as of 2019, 32 states and the District of Columbia exempt reflexology from the definition of massage, while four states do not require licensure for massage therapy, and therefore also do not regulate or license reflexology.

As a result, none of Nebraska’s neighboring states require occupational licensing to work as a reflexologist.

Though LB347 was unanimously advanced to full legislative debate in 2018, a filibuster in the Unicameral, supported by the massage therapy industry, prevented its passage in 2019.

Versions of this bill have been introduced several times, and it will likely return in the 107th Legislature.

Conclusions: Challenges and Opportunities

As the Legislature and its committees continue to work through the first five years of licensing reviews, there will be more opportunities to identify regulations that have outlived their usefulness. As with the infamous horse massage[vii] license repeal in 2018, we might expect more licenses to raise questions as reviews are completed.

The review process, likewise, continues to keep the eyes of legislators and staff on all bills that would add new licensing—and ultimately more review time—to state law. The process itself is a great starting point for those who wish to limit new government regulations of the labor market.

The passage of universal licensing bills in two of our border states—Iowa and Missouri—suggests that if the Nebraska Legislature wishes to remain competitive with other states, it will be necessary to continue to drive occupational licensing in a less-regulated direction.

ENDNOTES:

[i] Timmons, E. (2018, April 30). More and More Jobs Today Require a License. That’s Good for Some Workers, but Not Always for Consumers. Retrieved September 15, 2020, from https://hbr.org/2018/04/more-and-more-jobs-today-require-a-license-thats-good-for-some-workers-but-not-always-for-consumers

[ii] Occupational Licensing: A Framework for Policymakers. (2015). Washington, DC: White House.

[iii] Legislative Information. (n.d.). Retrieved September 23, 2020, from https://csorsfu.com/occupational-regulation-legislation/

[iv] Boehm, Eric. Reason Magazine. (2018, April 18). Nebraska Just Passed a Major Occupational Licensing Reform Measure. Here’s Why It Matters. Retrieved September 23, 2020, from https://reason.com/2018/04/18/nebraska-just-passed-a-major-licensing-r/

[v] Lauterbach, Cole. The Center Square. (2020, June 08). Ducey signs occupational licensing board reform into law. Retrieved September 23, 2020, from https://www.thecentersquare.com/arizona/ducey-signs-occupational-licensing-board-reform-into-law/article_effb70cc-a9cd-11ea-bf99-1b358959e4f3.html

[vi] Veto Letter Published in the Nebraska Legislative Journal. Retrieved September 23, 2020 from https://nebraskalegislature.gov/FloorDocs/106/PDF/Journal/r2journal.pdf#page=1495

[vii] Sibilla, N. (2018, April 23). Nebraska Stops Horsing Around, Legalizes Massage Therapy For Horses. Retrieved September 23, 2020, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/instituteforjustice/2018/04/23/nebraska-stops-horsing-around-legalizes-massage-therapy-for-horses/